By now you've seen the jokes about the "girlboss," and her depoliticized, so-called "feminism" that can be achieved through climbing the corporate ladder or buying an expensive pair of shoes. You've seen the scathing takedowns of women politicians like Hillary Clinton for their parts in U.S.-perpetrated atrocities in the Middle East. And you've seen videos of white woman after white woman calling the cops on Black people in their communities, and the lethal power of white women's tears when called out for racism.

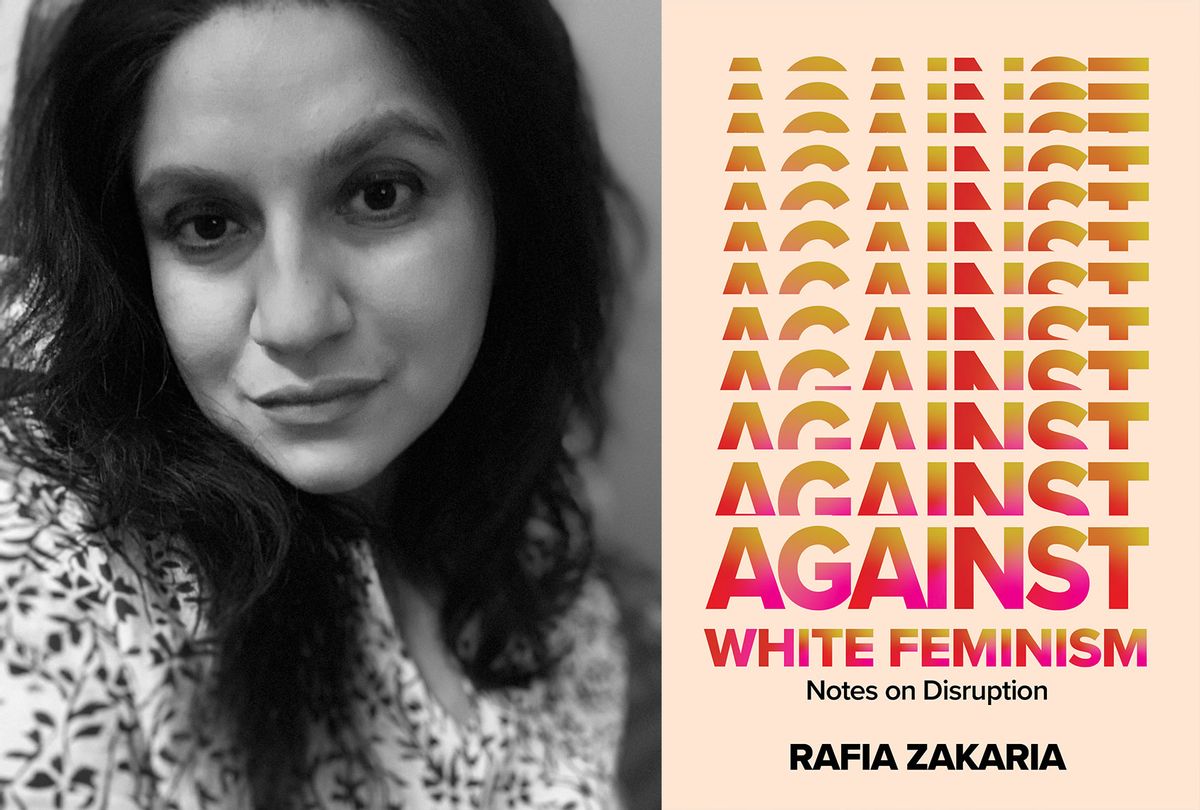

What does all of this have in common? According to Rafia Zakaria, an author, lawyer, domestic violence survivor and tireless voice for women of color-led feminism, in her new book "Against White Feminism" (W.W. Norton & Company, Aug. 17) all of this extends from white feminism. White feminism, Zakaria notes on the very first page of her book, isn't defined by an individual's race, but their refusal "to consider the role that whiteness and the racial privilege attached to it have played . . . in universalizing white feminist concerns, agendas and beliefs as being those of all feminists."

Because of this "universalizing" of white feminist concerns, Zakaria tells Salon she faced an uphill battle at times to get her bold, unapologetic analysis of the violent harms of whiteness in feminism over the finish line.

"I won't lie, I had to fight over a lot of sentences for this book, and really stand my ground," she said. "It was difficult when those I worked with wanted to help me, but could be put off by the brazen way I wanted to say things. Those moments were difficult, because it's a very thin line from working with allies to being bogged down by the usual tenor of these sorts of conversations."

Nonetheless, Zakaria overcame these barriers, and "Against White Feminism" is on shelves now. A bold call to action to eradicate white supremacy and neoliberalism from feminism in order for the movement to have a future, Zakaria analyzes the historical ties between white women-led suffrage and imperialism, and the dangers of global philanthropy that doesn't seek input from supposed beneficiaries. She condemns the opportunism of white women who have installed themselves as the saviors of women in the Middle East by advocating military action in these regions, and calls on western readers to consider why we define cultural crimes like "honor killings," while treating white-perpetrated intimate partner violence as an aberration.

In an interview with Salon, Zakaria talks about getting the book off the ground, why she sides with the teens roasting "girlbosses" on Twitter, how we're already seeing white feminism shape the response to the developing crisis in Afghanistan, and more.

Your book immediately gets personal with your introduction set at a wine bar with a group of white women feminists. Here, you raise what you call the "cult of relatability," and how white, mainstream feminism has prized expertise over experience. What is the mental toll of scenarios like this over time? How did you find the energy and ability to write this book?

With repeated situations dealing with white feminists like that, I felt I was dealing with the reality of exhaustion on one side, and the demand of keeping at this fight and trying to change things. What gives me strength to write the book is, I truly feel most women who have faced challenges like I did, from being an immigrant, to economic challenges, to being Muslim, don't get a platform. If I have a platform, I feel a sense of duty to say what I know women in those situations feel and think, but don't get heard.

I looked at it as a collective thing that I was doing — I wanted to give women who undergo these situations a frame to analyze them, and a vocabulary to talk about it. And from recognizing that we are living in a transformative moment where things are changing fast, there's an opportunity to inspire others to look at things from the perspective of women of color, who haven't been able to get the attention they deserve.

You examine the ties between British white women's suffrage movements and expanding imperialism in the 19th century in the context of how white women tend to make themselves the stars of women of color-led feminist activism to this day. Why do we still see this today, when we now live in a time when women of color are supposedly able to speak for ourselves?

There are feminists who are very reluctant to have conversations about race, and insert that into mainstream feminism. There are too many white women who see women who are disadvantaged by race and gender and class, as a challenge to white women's occupation of the whole category of gender.

Then of course, when you have that kind of power, they don't see any issue in speaking for women of color. Right now, everyone is talking about Afghanistan and Afghan women, and again and again, I see on TV, white people discussing amongst themselves. There's no effort to include Afghan women, or only the Afghan women who have benefited in some way from the U.S. aid economy — it's never Afghan women who have lost family members to U.S. bombings, never any Muslim feminists who could have offered interpretations of Sharia that are bold and expansive and gender-equal. There's no self-consciousness at all on the part of white feminists.

My book is sort of a "shut up!" in that sense, really challenging their role in speaking for everyone and making themselves the universalized unit that is then considered the feminist agenda. Woman is white woman, and therefore what the white woman wants, what her agenda is, what she thinks should happen in a situation, is believed to be what all women want.

You're critical of how modern neoliberal feminisms have become "depoliticized" over time when we frame feminism as a job you can get, or a power suit you can buy. Recently, the "empowered" capitalist woman has gotten the meme treatment with the popularizing of "girlboss" jokes online. Do you have thoughts on this anti-girlboss discourse? Have you found any enjoyment of these internet jokes while writing your book?

The whole project of the book is essentially to put the fangs back in feminism. By that I mean very pointedly reinvigorating feminism as a political movement, and not just as any choice that any woman makes. I don't believe in choice feminism, I don't believe all choices women make are somehow right and feminist because a woman made them. Choice feminism is at the heart of girlboss feminism, because girlboss feminism is ultimately an individualistic recipe where you're climbing the ladder, breaking glass ceilings, and you don't really care and are taught not to care about the other women, particularly women of color.

The book and my challenges to girlboss feminism focus on thinking of success and achievement in ways that are not perversely individualistic and capitalist. The book has some ideas about how that can be done, and not just saying, "Let's all be nice to each other!" I'm saying pointedly to white women, girlboss types, that they are hurting the movement, and doing what they're doing because of their racial privilege. The antidote is for white women to put that aside, and reconsider their own expectations, understand commitments to justice and ceding space are rewards in themselves — you are actively part of something that's bigger than you!

Speaking of girlboss discourse, there's growing skepticism of figures like Hillary Clinton who were once revered as feminist icons, but today are getting a lot of heat for their participation in U.S. military efforts and war crimes. What's changed in our cultural reaction to these women? And what is the significance of white women being leaders in brutal war efforts in the first place?

My hope is people are seeing the connections between white women's demands for themselves and the havoc they've wreaked on the world. In the '70s and '80s you had women like Catharine MacKinnon and Andrea Dworkin and their demands, enshrined in the Violence Against Women Act, was they wanted safety from violence. They wanted the state to provide that. They embraced a carceral idea of safety for white women, and at that time, there were Black and Latino women who objected to domestic violence laws that required the police to arrest someone at every domestic violence call. The consequence was that Black men were imprisoned at four, five times the rate of white men, and you had mass incarceration over decades and decades. The domestic violence law isn't the only reason for mass incarceration, but it does have some responsibility.

Then you have 9/11, and white women like Hillary Clinton, all demanding protection from terrorism, embracing the course of power of the state to bomb foreign countries. What we have now is a completely wrecked Afghanistan, Iraq, endless fighting in Syria. These are the consequences of white women putting themselves first constantly. Even now, they're getting some heat, but they're not getting enough. No one is talking about how you were responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths.

As you point out, endless war efforts are often held up by feigned concern over women's rights in countries in the Middle East. Why is it that the same people who act concerned about these issues abroad often have little to say about the rampant human rights abuses of women, especially women of color and immigrant women, in the west?

The Kool-Aid fed to American women is, "Don't complain because you're better off than all those other places." That's an outright deception. As I discussed in the book related to cultural crimes, you have honor killings, these crimes understood to be rooted in specific cultures. If a husband kills a wife in Pakistan, it's an honor killing, where if a husband kills a wife in the U.S., it's intimate partner violence.

The difference in categorization has a very specific political objective, attached to a specific world view, that says that other cultures are deeply flawed. When these acts of femicide occur in those cultures, they're somehow endemically tied to the cultural beliefs of that culture. If the same crime happens between two white people in Nebraska, that's just an aberration, an outlier, the culture isn't really that bad.

That imbalance promotes the supremacy of white feminism, as the feminism everyone should adopt if they want to be feminists. We're not acknowledging a situation, or the hardships of immigrant women, women of color within the U.S. are going through. The idea is, whatever you're going through is better than where you came from, or the deliberate framing of other cultures as endemically un-feminist, is geared to maintaining the supremacy of white American feminism. We need to build a global system that's very different from the one we have today.

Your exploration of how some adult women choose female genital cutting (FGC) for themselves is particularly powerful in context with their shock at how women in the west go through botox, breast implants and other surgeries to meet a western beauty standard. Why are revelations like this so shocking to Western women? Where does Western women's superiority complex toward women of color around the world come from?

I had to really fight to get that included in the book, on FGC. Even before the book, I tried so hard to get that bit of research I'd been working on published within western media, and there was nobody who would take it. And it took a lot to get it in the book.

We see this shock and this superiority because for so long, white feminism has been conflated as just feminism. When it's questioned, western women respond very defensively because they think their precepts and critical evaluations of FGC are not connected to their race. They just connect it with feminism. They can't see and will discard any argument that I'm making as "moral relativism." But it's not moral relativism, because I don't personally support FGC, and definitely don't support it for minors. Beyond that, I think this idea that white people decide what is and isn't problematic in some cultures is deeply flawed, unless those same standards are applied to white cultures.

It's dangerous to talk about white culture, or white anything. There are 20 states that want to ban the teaching of critical race theory and attempts to ban sharia law. These very populist calls to action are because one way to unite white women has been to get together and criticize women of other cultures. If you want to have a women's caucus and get Democrats and Republicans together, you can have someone come and talk about honor killings in Jordan. Then everyone can unite against that idea of how honor killings are so bad, and those women are so unlucky to live in an inherently un-feminist culture that condones that, and their feminists are so weak and useless that these things continue to happen. It's a great source of unity for white women.

Your chapter on the racism and otherization in how we name and police some acts as crimes like "honor killings" or "infanticide" was intriguing. In exploring this context both in your book and previous work, have you faced pushback or accusations from people who say you're "defending" these acts? Why is it so important to understand the racial lens through which we see certain crimes?

The failure to see through a racial lens, to refuse to articulate whiteness as a race, that's permitted the dominance of whiteness. The book came out Tuesday, and I'm getting tons of tweets from people saying I support the Taliban, who haven't even read the book yet. I'm going to get lots of pushback on the FGC issue, the honor killings, because it's been such a central pillar to white feminism — this condescension toward other cultures, this idea that white culture isn't really a culture. If you talk about the number of men who kill their wives among white people, that's not something connected to a culture — that's just man against woman. When a brown person kills his wife, that's inherently connected to the culture.

If feminism doesn't excise this white racial privilege from the movement, then the movement is losing relevance. It must cohere itself in a way that we can see it's patriarchy behind honor killings. That's the same mindset that leads men to kill their wives in the U.S. as well. We have to transform our frame for feminism to be made truly collective and international, and I want especially for women within the U.S. to recognize the same patterns of white supremacist violence that exist against communities of color here are replicated in foreign policy abroad.

In your book, you examine how philanthropists rarely actually listen to women on the ground about their needs, and are often part of upholding global inequalities. Of all the examples you give, what were some of the most egregious or shocking to you? (I know for me, the Gates Foundation giving chickens to Bolivia really stood out!)

Gosh, there's so many. To me, it's the stoves — there were hundreds of millions of dollars spent by a conglomeration of the biggest actors in the global aid industrial complex, and this smug belief that "we're going to make these Indian women into little capitalist producers, and that will equal empowerment." We've diluted "empowerment" to the point where it's any technocratic program that says it's going to benefit women.

In this case, they give Indian women these clean stoves and expect they'll immediately abandon their wood burning stoves and be excited they can now go get a job outside the home and don't have to collect wood. But they found it didn't work at all. Here you have an inability to place value on women going out and interacting with other women every day, and exchanging news, sharing resources. The idea was, why would they want to go out with other women and look for wood? The women said, "We like going out and collecting this wood with people in our community. Our role in the kitchen does give us power within the family, the food we want to cool that is traditional, we can't cook on the stoves you've given us. And if the stove breaks, we have no idea how to fix it."

It just shows how white feminist assumptions about the aspirations of other women, and what women find rewarding, were so unquestioningly replicated and assumed to be the desires of rural Indian women. It wasn't one, it was so many organizations including the UN, all of them together, and no one paused to think of that.

There was one program that gave $4 million to give 75,000 Afghan women job training, and there were, like, three women that benefited from it. You have waste on this gargantuan scale, and it shows the point of these programs isn't to help women at all — it's to provide a cover or purchase a sort of virtue signaling, the international version of a blonde white woman taking pictures with African kids and putting them all over her Instagram. The success of these programs isn't the point.

In your final chapter, you explore revelations of racism and abuse from leading white women-led feminist organizations reported on last summer. How did it feel to be writing your book while that was happening?

There are a lot of people, other women of color who are writing and doing the work. The issue is that the work doesn't get attention. That report about NOW and other organizations is an excellent piece of investigative journalism but you hardly hear about it, when this is the biggest women's organization in the U.S. It just gets pushed under the rug, because white feminists are so invested in their self-image as the benefactors of the world. That's the way these sorts of issues that involve any racial dimension are treated. And it's the ultimate defensive response, of "I'm not going to talk about race." But feminists' refusal to talk about race has put it on life support, and if we want to salvage anything from this movement, you have to remove white racial privilege.

Shares