Steven Pinker's new bestseller, "Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters," is filled with riddles and quizzes and problems to ponder. Reading it, I bombed on every single one. The point, however, is not to make us all feel like dummies. It's not even just to illuminate how easily any one of us can leap an erroneous conclusion; that's a very human thing to do. It's to remind us that we are the very creatures who can make riddles and quizzes in the first place.

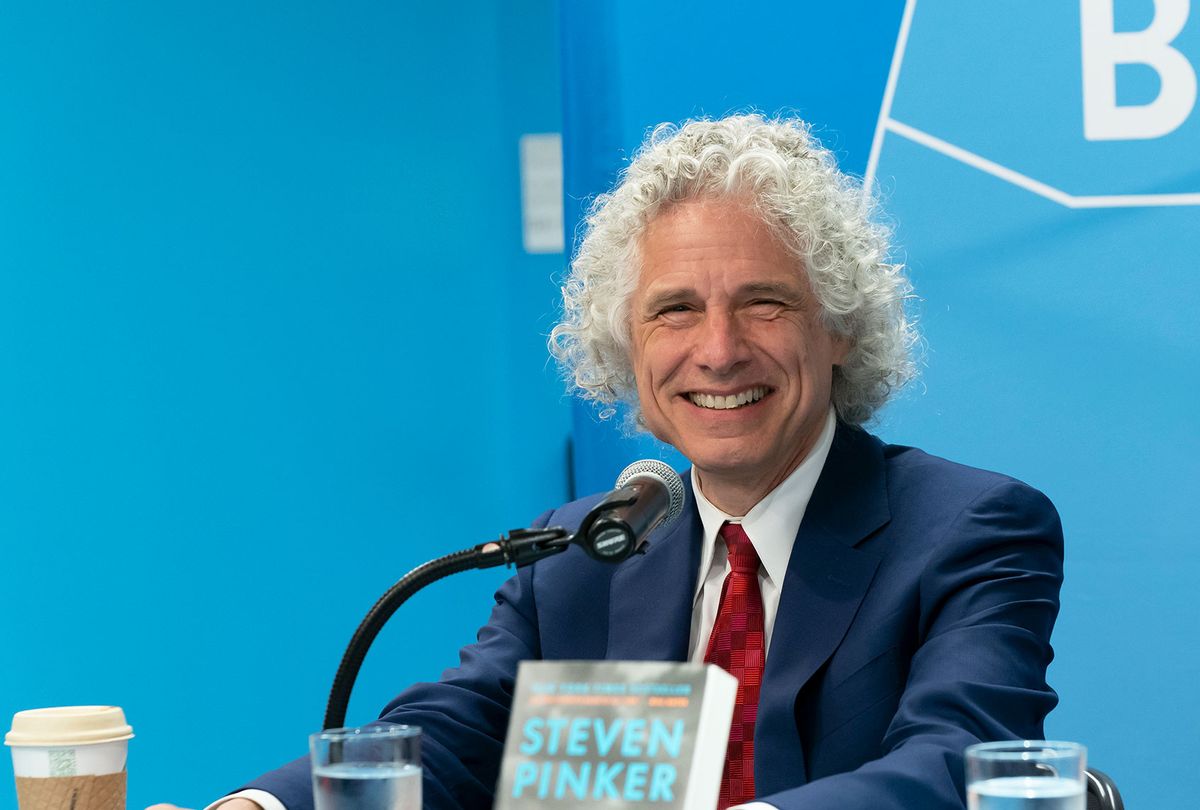

As a popular yet controversial public academic figure, Pinker knows that the real world often revolves more around winning arguments than solving problems. Changing the paradigm, then, means walking the walk. The Harvard psychologist seems aware that in advocating for critical thinking and free speech, he's emboldening his audience to question his ideas too. "Rationality," the book, and rationality, the ideal, are about not about starting a fight but having a conversation. And so, while disagreeing at times, that's just Pinker and I recently did. He talked to Salon via Zoom about mansplaining, why rationality gets a bad rap and what he learned from getting called out on social media.

As always, this conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Rationality has a bad reputation at this moment in our culture where everybody is entitled to their own feelings, and feelings are mistaken for facts. If you were to make the case to me that rationality is not uncool, how would you do it?

At least since the Romantic movement, rationality has been contrasted with enjoyment, emotion, human relationships, which is just an error. It's a mistake. Rationality is always deployed in service of some goal, and there's nothing illegitimate about human goals like pleasure and love, all the good things in life. The question is how best to get them. How do you nurture a relationship? How do you achieve the goals of satisfaction, pleasure and fulfillment in whatever you have set as your goal?

How do we make rationality cool? There are always a give and take between the negative stereotypes of people who are too rational — the nerd, the geek, the brainiac, the robot, the Spock. We do sometimes put rational people in a heroic light — Anthony Fauci, "The Queen's Gambit." I do think that probably there is some good that can come from popular culture and journalism glorifying rationality when it is deployed in pursuit of goals that we can agree are worthy.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

I often think of the ways in which emotion is not seen as cool — "You're hysterical, you're overreacting" — and all of the things particularly that are applied to women when we use our emotions.

I have to add that men are vulnerable to irrational notions, too, particularly vengeance, honor, insults, machismo. So emotion is by no means gendered.

The way in which they are perceived and labeled is different, though, because certainly a man being vengeful is cooler than a woman being hysterical.

Which is a basic problem, yes.

You outline all of the ways in which we have, as a species, always been rational. Our earliest ancestors used rationality to survive.

Our species has taken over the planet, so we've done a whole lot more than survive. The reason we've managed to infest so many niches on planet Earth is because we're not narrowly adapted to one particular ecosystem, but we live by our wits going back to as long as we've been human. We have mental models of how the world works, including how plants and animals work, and physical objects. We play out scenarios in our mind's eye so that we can bend the world to our will by tools, traps, poisons, and coalitions, reading each other's minds so that we can cooperate and attain things collectively that we can't individually. That does go way back.

In writing "Rationality," I did in some ways resist the narrative that has become popular in my own tribe of cognitive psychologists — and I do it myself — to try to convince students and readers of what an irrational lot we are, all the long list of fallacies and biases that we're vulnerable to. We are. We do make errors. On the other hand, it was us who set the benchmarks of irrationality against which we can tease each other about committing fallacies. We are a rather unusual species in how clever we've been in developing tools and technologies.

That set up a tension that drove the book, because, the current era is unprecedented. We've developed an mRNA vaccine for COVID in less than a year. We're on the verge of exploiting fusion power. Rationality is being applied to new domains like evidence-based medicine, evidence-based policing, moneyball in sports, poll aggregation in journalism. At the same time, we are inundated with fake news, and medical quackery, and paranormal woo-woo, and post-truth rhetoric. So what's the deal with our species? Why is there so much rationality inequality?

Rationality is often flipped on its head, where it seems like the least rational people are operating under a guise of rationality. "Well, you have a minuscule chance of getting COVID," "If a woman wants an abortion, she's got six whole weeks to get one. We're giving her plenty of time." It's what you talk about with the availability bias, and the ways that rationality is used in defense of things counterintuitive to us as a species. I want to ask you about using false logic to appeal to emotion.

Appealing to emotion is all right if it's an emotional goal or pursuit that we can all agree is worth pursuing. It's when it leads us into doing things that don't attain what we want, such as health, happiness, well-being and knowledge, that it can be a problem.

We can always step back and question our own feeling of being reasonable, and it's the forums in which people get to criticize each other — freedom of the press, free speech — that allow us to attain rationality as a society, which we would never attain if every individual was left to pursue it for himself or herself. That is one of the themes of the book. I'm trying to resolve this paradox of how we can be so rational and irrational at the same time.

Part of the answer is that in a lot of the issues that concern us, no individual can be counted on to be particularly rational, because our goal is not always objective truth. Our goal can be to seem like a know-it-all, to glorify our tribe, to win acceptance in our peer group, in our clique. And if our particular clique holds on to sacred beliefs, then it's in one sense perfectly rational to say things that will make you accepted within your peer group and not make you a pariah. I mean, it's rational for you as an individual, not so rational for society if everyone is just promoting the beliefs that enhance their local glory. As a society, what we want is the truth, and those are two different goals. The only way that we can hope toward achieving or approaching the truth is if we're allowed to criticize each other's ideas, and so if someone claims to be rational, someone else can use a rational argument to show why they're mistaken.

You write, "So much of our reasoning seems tailored to winning arguments." How would you define the difference between winning an argument and having a rational conversation?

There's a classic list of dirty tricks that you can use to win an argument that don't bring you any closer to the truth, like ad hominem argumentation. You try to discredit your debating opponent on personal grounds, to imply that he or she is morally tainted. There's guilt by association. You try to discredit someone in terms of who they hang out, who they've published with, what conferences they've gone to. Argument from authority. You say, "Well, so-and-so has a Nobel Prize. Are you going to argue against him?" There's a long list that are part of the curriculum of critical thinking courses.

We're primates. We are vulnerable to dominance signals, such as the person who has mastered the hard stare, the confident tone of voice, the deep voice. I feel odd as a male explaining to a female what these tactics are. This would be a prime example of mansplaining. I'm sure that you could identify these tactics far better than I could, although men do it with each other too, so I am familiar with them. So yes, there are ways in which you can try to dominate an argument without necessarily having a more meritorious position.

You state very clearly later in the book that we can't just blame social media for this. This isn't just all the fault of Twitter. So what, if not social media?

Certainly a lot of the forms of irrationality that are concerning us now have long been with us. Conspiracy theories probably go back as long as language. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion more than a century ago led to pogroms of anti-Semitism across Europe. Certainly belief in paranormal is probably the default in human psychology. What is religion but established belief in paranormal phenomena, miracles, and saints, and an afterlife? Fake news used to take place in supermarket tabloids.

I think it may be too soon to know how much of it has been driven by social media compared to AM talk radio and cable news. We actually do know that cable news has a polarizing effect. Whether social media have deepened those divisions, I don't think we don't yet know. I will admit that since publishing the book, I have been more open to the possibility that social media have been making us stupider. I myself, in fact, was the victim of a social media attack, which was described in the New York Times under the headline "Social Media is Making Us Dumber." So I of all people should acknowledge that.

I've been influenced too by Jonathan Rauch in his book "The Constitution of Knowledge," which developed a similar argument to the one that I developed — mainly that we're often rational only by virtue of certain norms, institutions and rules that make us collectively more rational than we are individually. Like fact-checking, like freedom of the press and freedom of speech, like peer review, like empirical testing. Rauch points out that social media almost seem perversely designed to implement the opposite of those conventions. Namely, you get a reputation not for accuracy but for notoriety, shock value, polarizing impact. There is no fact-checking. There is no pausing for reflection and verification, but things can be instantly propagated. There are certain things simply built into social media that are the opposite of the guardrails and rules of the game that can make us rational.

You also lay out case for hope. You mention that when we talk about bending toward justice, the moral changes in our world have often begun with rational thought. I wonder looking around me now, who is going to make that rational argument that's going to turn this train around right now?

Partly, or in large part, we have to reinforce, savor and celebrate the rules of discourse that encourage rationality, which is one of the reasons that I am an advocate of free speech, of viewpoint diversity in academia and journalism. If there is a monoculture of belief, and if there are punitive mechanisms that prevent people from criticizing other ideas and voicing their own, then that is a way of locking us into error, bad habits and bad conventions. There should be, I think, the promotion of norms of rationality. Instead of the current rules of, say, op-ed argumentation, namely you try to win, you never admit a mistake, the idea is that you should bracket your claims with uncertainty, engage in what's sometimes called steel-manning. It's the opposite of straw-manning, namely. you try to state the position you disagree with in as strong a form as possible instead of as weak a form as possible, where you can knock it over. The habits within journalism and academia of going to data when data exists, and not just repeating mythology or strengthening mythology. Those would be some of the ways.

You point out that most of us are actually no impervious to evidence. The question then is how do we implement that?

It's in education that we need to really be implementing these kind of rational strategies and this civic-minded thinking. How do we do that when it feels like there is a real, very conscious attack on critical thinking in our educational system right now?

The tools of rationality should be part of the curriculum from early on. Probabilistic thinking, logic, causation and correlation. Fallacies of reasoning, that is, lapses in critical thinking like guilt by association, arguments from authority. And the reason is the problem with lobbying for any change is that everyone thinks that what they're arguing for should be the most important thing in education. It should be music. It should be art. It should be math. On the other hand, I think a case could be made that the tools of rationality are a prerequisite to everything else, and so they should be prioritized. Part of it's education.

Part of it is informal norms, which are hard to implement from the top down, but just the expectation that you should not argue from anecdotes, that you should not confuse causation and correlation. You shouldn't reduce your opponent to a straw man. To the extent that we can just spread those norms and values, and the fortification of the mechanisms of collective rationality, like free speech, like fact-checking, like establishing reputations based on accuracy rather than notoriety or an ability to rile up the crowd. Peer review itself has got its problems within academia, but it's probably better than no peer review, but maybe we should look for even better mechanisms. The rules, the infrastructure of rationality has to be fortified, because we can't count on the rationality of every last individual.

Do you think that this is possible right now, in this incredibly polarized moment?

I think it is, because if we look at the questions, the issues that polarize people, it's actually not everything. Certain issues get somehow designated as bloody shirts, as hot buttons, often unpredictably. Who would have thought that getting vaccinated or wearing a mask during a pandemic would be? I don't think there's a political controversy over filling potholes, or taking antibiotics, or flossing your teeth.

The anti-floss movement, coming right up.

It could happen, so we should be conscious of the phenomenon of politically polarizing an issue, and take steps to try to prevent that from happening. I know that certainly my fellow scientists have been very poor at that. In fact, oblivious, ignorant. For example, the way that climate change became a left-wing issue, a massive strategic error. It didn't have to be that way. It used to be that environmentalists were on the right as often as on the left. Sometimes even more so.

As much as I admire Al Gore, to have him be the face of climate change was a big mistake, because then if a Democratic vice president or presidential candidate was in favor of something, those on the right said, "That's reason enough for us to oppose it." I think that for the scientific establishment to consistently brand itself a wing of the political and cultural left is a big mistake, because that's what will lead people on the right to write it off. So to the extent that we can keep issues politically neutral, we'd be more likely to get people from across the political spectrum to agree to evidence, and logic.

Shares