I first saw “Assassins,” the late Stephen Sondheim’s musical, in high school at a theater festival, after sneaking inside. I was at the festival because I had won a playwriting contest, and I was supposed to be at a rehearsal for my own play. But as soon as the music of “Assassins” started, a circus-like tune, I was spellbound. I couldn’t leave.

Sondheim composed the music and wrote the lyrics for “Assassins,” with a book by John Weidman, and the show premiered Off-Broadway in 1990, closing after only 73 performances and mixed reviews. Sondheim’s name may have helped the performances to sell out, but as the legendary Frank Rich wrote in the New York Times: “‘Assassins’ will have to fire with sharper aim and fewer blanks if it is to shoot to kill.”

After Sondheim’s death on Nov. 26 at the age of 91, tributes poured in about the musical theater legend, with many praising his passionate songs, his twisty lyrics that play so much with language, his love of writing showstoppers. Obituaries and odes to Sondheim highlight “Company” (1970), 1979’s “Sweeny Todd,” and “West Side Story” (1957).

Not many people bring up “Assassins.”

NPR’s list of “10 Stephen Sondheim’s Songs We’ll Never Stop Listening To” doesn’t include a single tune from the show. It wasn’t exactly a flop, but it’s not exactly celebrated, either.

RELATED: Bet your bottom dollar that NBC’s “Annie Live!” will usher in a new inclusive era for an old classic

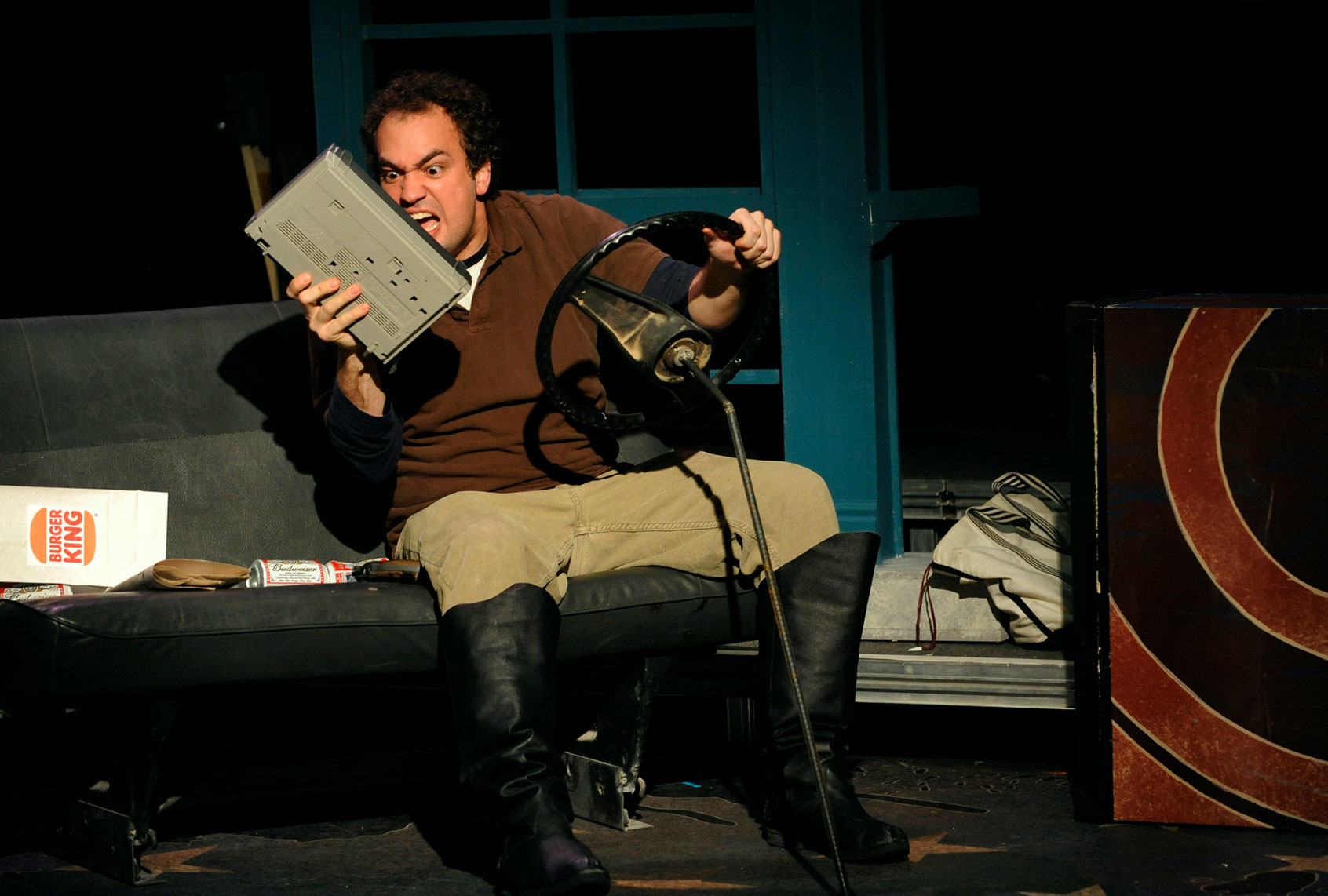

Through vignettes, “Assassins” tells the stories of presidential assassins and would-be assassins from John Wilkes Booth to John Hickley Jr. As with Sondheim musicals like 1986’s “Into the Woods,” a narrator, called The Balladeer, loosely strings the tales together. A bleak sideshow provides the staging inspiration. The set often has the feel of a shooting gallery with bells that ding or buzzers that blare. The calliope-heavy incidental music sounds like a carousel. It’s “Something Wicked This Way Comes,” but for presidential murder.

The songs are just as catchy, melodic, and surprising as most Sondheim — even if a bit reminiscent, sometimes startlingly so, of “Into the Woods,” especially its prologue and “Last Midnight.” The rhymes sound just as strong with couplets like, “Some guys think they can’t be winners./First prize often goes to rank beginners.” And Sondheim’s work is certainly no stranger to violence. “Sweeny Todd” has a murderer — has cannibals even.

But “Assassins” has only murderers.

Even the Balladeer doubles up on roles and plays Lee Harvey Oswald in most productions. Early reviews criticized all that violence, with some accusing the show of being “unpatriotic” in the midst of the Gulf war. “Talk about bad timing,” is the first line of a Los Angeles Times piece about the show.

But is there ever a good time to mount a musical in America about assassins?

In the show, assassins hang out through space and time in a kind of killers’ clubhouse where they encourage each other. Charles Guiteau (assassin of President James A. Garfield in 1881) gives 1975’s Sara Jane Moore shooting practice. Moore and Squeaky Fromme, a Manson girl who, with Moore, attempted to kill President Gerald Ford, take shots at a bucket of chicken.

A lot of guns go off onstage in “Assassins.” Characters wave guns in the melodic “The Gun Song Ballad.” Guiteau points one at the audience. Guns seem to always be in the hands of the characters, less of a prop and more of an extension of their bodies. A dog is shot, a child crying for ice cream threatened with a gun by his mother, Moore.

There isn’t really a central story to “Assassins.” It’s more like a central feeling, which, unfortunately, is one echoed by some modern-day mass shooters. The assassins feel alone, alienated by sadness, unrequited love, their failures. They think killing someone known will make them famous, happy. Make them known by proxy. Or, that it will change the world they’re so unhappy with: “We do the only thing we can do./We kill the president.”

In the ’90s, “Assassins” productions were cancelled after school shootings. Productions were cancelled after 9/11. But a revival is on Off-Broadway right now, with the same tepid reviews that dogged the original, including one from the New York Times that mentions the most recent shooting at the time of print, the shooting death of cinematographer Halyna Hutchins on the Alec Baldwin “Rust” set.

Of course, there has been another shooting since that review. Of course, there will be another before I finish writing this.

In an America after a Donald Trump presidency, it’s hard not to draw contemporary parallels with lyrics like, “What I did was kill the man who killed my country,” and the constant sadness of the characters, mostly men, that they are alone, being left behind by a world that they feel no longer has a place for them.

Only one scene shows an aftermath of violence: the assassination of JFK, the climax of the show. And even the bystanders singing about where they were when they heard the news eventually come to a kind of grim resolve by the end of the song: “Nothing has really ended/just suspended.” It feels like a weird justification for the musical itself.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In parts, “Assassins” can feel extremely dated. Several of the assassins are immigrants with heavy accents. The mental health issues of characters like Moore and Guiteau are played for laughs. Just a few months ago, the Shaw Festival canceled an upcoming staging after rights holders refused to allow the production to change the n-word, sung by Booth in a tirade against President Abraham Lincoln.

A few months after seeing “Assassins” as a high schooler, I saw a then-new play called “Front” at a university. Written by British playwright Robert Caisely, “Front” tells the story of Londoners during the Blintz in WWII. Though not a musical, the characters sing wartime songs a capella in starkly stunning moments. And the story focuses on women: women working in bomb factories, women left behind as husbands go to war, a daughter growing up alone.

Both “Front” and “Assassins” taught me that history is alive, still happening. That history can be sung, and that stories are not only to be found in imagination (“Company”), other art (“Passion,” “Sunday in the Park with George”) and faerie tales (“Into the Woods”) — but in the past. Decades before “Hamilton” dominated musical theater, we had “Assassins,” which uses some historical text, including a poem Guiteau wrote the morning of his execution and read aloud at the gallows.

Perhaps Sondheim’s musical has not aged well and should not be staged lightly. I wonder, for example, about the line asked by Oswald, “What should I do?” And Booth, who the characters describe as their “pioneer,” answering: “You should kill the president of the United States.”

Does the line get a laugh, as it did in the video of a 2004 production on YouTube? Or, is there silence in a newly opened theatre in 2021, knowing that this dark joke isn’t a joke at all, that violence like it keeps on happening. I may never know, as the revival of “Assassins,” lukewarm reviews and all, has sold out its extended run after the composer’s death.

Sondheim was always at his best when writing about darkness, composing terrible things in beautiful, soaring melodies. Terrible things are a lot of history. It’s what we endure. And as we know, those who don’t learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Or, to sing it.

More stories like this: