If you’re a liberal Democrat, you’ve probably been feeling cursed for a while. Every time it seems like things might get better — for America, the world or both — bad luck strikes, and the result is a massive setback.

Just look at this decade. Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election with more votes than any other candidate in American history, but because Donald Trump refused to accept defeat, the moment was soured. Now Republicans are trying to strip away voting rights, potentially empower their own partisans to overturn election results and otherwise render it difficult for Democrats to ever win national power again. Faced with Mitch McConnell’s intransigence and a pair of Democratic senators who refuse to dump the filibuster — even though that arcane procedure literally makes it impossible for their own party to govern — Biden has also taken the blame for Republican mistakes, notably the bungled Afghanistan war (started by George W. Bush and concluded by Trump), which Biden wrapped up with an admittedly ugly withdrawal.

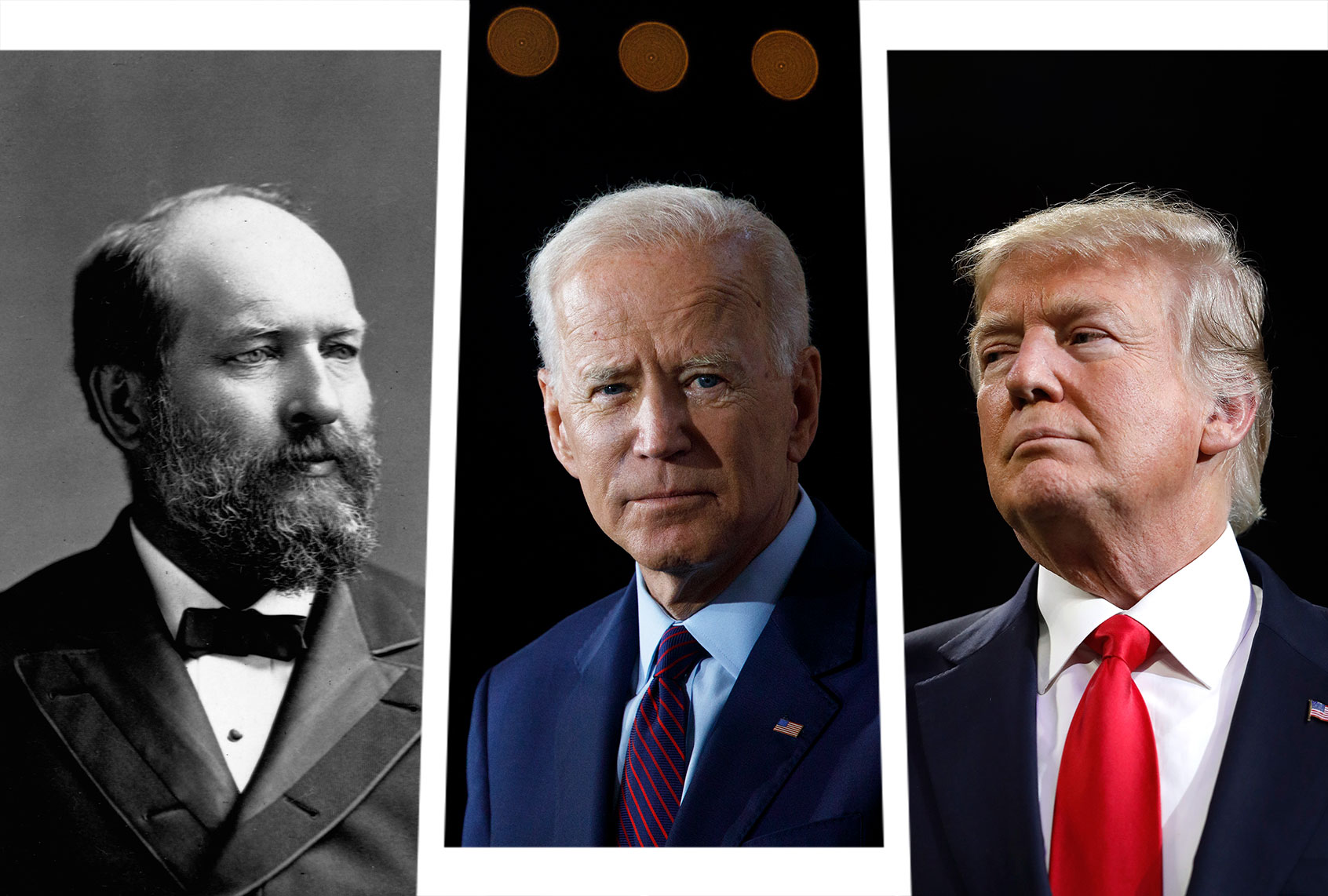

Now Biden and the Democrats face the ominous prospect of entering the 2022 and 2024 elections as unpopular incumbents, with historic precedent suggesting they will likely lose the first of those and face a difficult path in the second. As a result, I’ve already written about the history of the 1934 midterm elections, which may offer Democrats a more hopeful precedent this year. To imagine what a favorable narrative might be for 2024, it may be useful to consider a president best known for sharing his name with a grumpy cartoon cat who dislikes Mondays. Enter James Garfield, whose story resonates surprisingly well today. Garfield’s tale is about great potential needlessly squandered, noble crusades repeatedly frustrated and atrocious bad luck reflecting the most squalid and stupid of human foibles.

RELATED: Can Democrats break the midterm curse? Maybe — consider the example of 1934

In other words, it’s a story today’s Democratic voters may well recognize.

Garfield was literally born in a log cabin in rural Ohio in November of 1831. Raised by a single mother who was desperately poor, he faced relentless bullying as a child and sought escape through constant reading and writing. Determined to better himself, he entered the workforce at 16 and held a number of jobs in early adulthood: Canal worker, carpenter’s assistant, janitor, teacher. He worked his way through college, had a religious awakening (somewhat surprisingly, he’s the only president who was an ordained minister) and was admitted to the bar. Those who knew him were struck by his intellect: He became fluent in Latin and Greek, was a talented public speaker and became well-known for his esoteric academic pursuits. Perhaps the most famous of these was his discovery of a trapezoid proof for the Pythagorean theorem, which he pursued during his downtime while serving in Congress.

To his immense credit, Garfield was horrified by slavery and became a passionate abolitionist. He joined the newly-founded Republican Party because its main purpose was to limit slavery’s spread. In 1860, when the Southern states seceded and launched the Civil War rather than accept the election of Abraham Lincoln, Garfield immediately supported the Union cause. But while many of his contemporaries only fought to preserve the Union, Garfield made it clear that the true moral cause behind the war was to end slavery. As a newly elected Ohio state senator, he could have avoided military service, but Garfield resigned his office and in 1861 enlisted in the Army. He eventually rose to the rank of major general and so impressed his contemporaries that in 1863 he was nominated to run for Congress from Ohio’s 19th district. He won that seat and held it until his victory in the 1880 presidential election. To this day, he remains the only sitting House member ever elected president.

This was not the only unusual thing about Garfield’s election. Based on the normal cycles of party politics, he shouldn’t have won at all.

Few presidents have entered office amid more turbulent circumstances than Garfield’s predecessor, fellow Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Official winner of the controversial 1876 election, in which both parties blatantly cheated, Hayes carried the nickname “His Fraudulency” until his dying day. He was only allowed to take office without an accompanying second Civil War through the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reconstruction, withdrew all remaining federal troops from the former Confederate states and starting the Jim Crow era of brutal racist oppression and segregation. Otherwise Hayes’ term was largely forgettable, other than his handling of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and inability to provide any material relief amid an economic downturn. The Republicans suffered massive defeats in the 1878 midterm elections, losing control of the Senate and sustaining further losses in the House, which was then divided four ways with the “independent Democrats” and the Greenback Party, as well as the official Democrats and Republicans.

Yet somehow, just two years later, another Republican won the presidential election: James Garfield. How did he pull that off?

First of all, the Republicans were deadlocked in choosing a nominee. Hayes kept his promise not to run for re-election, and the apparent frontrunner was former President Ulysses S. Grant, seeking a third term after four years out of office. He was challenged by two popular insurgents, Sen. James G. Blaine of Maine and John Sherman, Hayes’ secretary of the Treasury. The party was split between warring factions: the “Stalwarts,” who wanted a patronage system for party loyalists, and the “Half-Breeds,” who backed civil service reform. There were also economic disagreements on tariff and currency policy, and Republicans faced an obvious electoral disadvantage, with Black people in the South largely stripped of the right to vote.

Garfield entered the Republican convention as a Sherman supporter, not a candidate. Even describing the Ohio congressman as a “dark horse” would be an exaggeration: No one following the 1880 election thought he was even in the race. Yet in a scene worthy of the movies, Garfield changed that with a half-improvised speech on behalf of his champion, one so well received it convinced the delegates that he was the man they’d been looking for. One passage stands out:

Twenty-five years ago this Republic was bearing and wearing a triple chain of bondage. Long familiarity with traffic in the bodies and souls of men had paralyzed the consciences of a majority of our people; the narrowing and disintegrating doctrine of State sovereignty had shackled and weakened the noblest and most beneficent powers of the national government; and the grasping power of slavery was seizing upon the virgin territories of the West, and dragging them into the den of eternal bondage.

It is easy to imagine why this would have electrified the assembled delegates. Garfield went through the Republican Party’s history, issue by issue, and cloaked their most cherished causes in the soaring moral rhetoric of a preacher. He reminded Republicans of their party’s highest ideals, which united them far more than the disputes between the Grant and Blaine factions divided them. His concluding argument was that delegates from both sides should join behind Sherman, yet as Garfield continued his speech, a contemporary reporter recalled,

curious remarks were made about it. Those who were utterly unable to recognize the secretary of the treasury in the ideal man whose portrait Garfield drew, begin to think that the picture was Garfield’s picture of himself. Suggestions to this effect have been frequently made to-day by men who are in no way hostile to Garfield, and who see in the course he has pursued during the Convention indications of an honest desire to advance his own fortunes.

As the convention dragged on, contemporaries later recalled, Garfield’s speech lingered in their memories. This unlikely moment, and its outcome, stands as a testament to the power of eloquence and charisma, and a reminder that the shape of history is not always decided by the cynical calculations of powerful business and political interests. Literature on the 1880 election makes clear that if the delegates hadn’t felt so stirred by Garfield’s appeal to their better angels, they would have picked Grant, Blaine, Sherman or some other alternative. Instead their inability to break the deadlock made the declared candidates look worse and worse, while Garfield looked better and better by comparison. Despite Garfield’s strenuous objections — he insisted he was not a candidate and wanted Sherman to be president — a stampede began in his favor, and he became the nominee.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

But how did he go on to win the general election after that? Presidential candidates in that era did little active campaigning on their own, so Garfield’s role was primarily about strategy rather than oratory. The Republicans did two things right: They repeatedly reminded the voters that their opponents were associated with white supremacy and treason, and they hit the Democrats on bad economic policy as well. To do the former, they brought up memories of the Civil War, slavery and the brutal mistreatment of African Americans in the South. Democrats described this as “waving the bloody shirt,” but Republicans dismissed that criticism for what it was — an attempt to vilify them for telling the truth. The major pocketbook issue was tariffs, and Republicans argued that the Democrats’ incoherent tariff policy might lead to lost jobs.

In the end, Garfield won — albeit by a razor-thin popular vote margin, less than 2,000 votes out of more than 9.2 million cast. (His electoral college victory was far more decisive, 214 to 155.) His presidency began with big promises, including plans to clean up government and fund a universal system of public education. His only actual major achievement, however, was one Supreme Court appointment. On July 2, 1881, after less than four months in office, Garfield was shot in the back at a Washington railroad station by a failed writer and lawyer named Charles Guiteau, who believed the new president owed him a lucrative appointment.

That wasn’t the end of the story: The gunshot wound was relatively minor, and even in the 19th century was potentially survivable. But Garfield’s doctors rejected the newfangled notion that they should wash their hands, and he apparently suffered a major infection as a result. To this day medical experts don’t exactly know what went wrong, but after a few weeks of apparent recovery, Garfield gradually declined and finally died on Sept. 19, two and a half months after the shooting.

If Garfield had survived, both his contemporaries and later scholars have agreed, history might have been different. He would have had carte blanche for at least the next few months after his recovery. The world had breathlessly followed every news report on his health, and during the period when he could still work after the shooting, Garfield considered initiatives to address racial inequality and further honest government. It’s entirely likely that in a full term he would have proposed creative policies we can barely imagine today.

Of course Garfield had his flaws. He sometimes moderated his positions in Congress out of political opportunism, and was implicated in a banking scandal that involved corruption in financing the Union Pacific Railroad. I don’t seek to depict him as a heroic martyr, only as an example of a political leader who genuinely wanted to do good things on a grand scale, but was frustrated by dreadful luck.

If there are hopeful lessons to be drawn from the Garfield story, we have to look past its conclusion. Political wisdom suggested that the incumbent party — the most progressive one of the time — was doomed in the 1880 election, but Garfield defied that precedent through the sheer power of his personality, rhetoric and idealism. On a more pragmatic level, Republicans grasped that they didn’t need to reinvent the wheel to overcome the hurdles of incumbency. They just had to motivate their most loyal voters, and refuse to waver in the face of bad-faith attacks by their opponents.

Finally, the Garfield story is another reminder that the old adage about history repeating itself remains true. It is frustrating when that means the bad luck of the past can come back to bite us in the present — but it is comforting because things can also get better, if we keep the past visible in our rearview mirror.

More from Matthew Rozsa on the lessons of American history: