The last two years of the pandemic have exposed a deep ignorance of public health among our countrymen. As evidenced by widespread, conspiracy-minded resistance to vaccination — plus the constant trickle of pandemic misinformation, from social media, pundits and podcasters alike — contemporary Americans might appear possess a weak grasp on statistics, biology, and the scientific method.

Yet it turns out this distinct brand of medical ignorance is nothing new. Rather, it is as American as apple pie. More than 200 years ago, one of the most famous doctors from the revolutionary period committed the exact same logical fallacy as Joe Rogan, who fallaciously attributes his Covid recovery to a "kitchen sink" cocktail of snake oil drugs and supplements.

The doctor in the mold of Rogan was Founding Father Benjamin Rush, the "father of American psychiatry," who despite his medical brilliance mistakenly believed that yellow fever could be treated by bleeding and purging. Many of Rush's colleagues urged him to see the error of his ways, but Rush literally practiced what he preached. The experience of treating his own infection, as he described it, was harrowing. His pupil "bled me plentifully and gave me a dose of the mercurial medicine," Rush said. Although his fever initially subsided, it later returned and Rush's pupil "bled me again….The next day, the fever left me, but in so weak a state that I awoke two successive nights with a faintness which threatened the extinction of my life."

Yet Rush ultimately did recover, and — like Rogan — falsely attributed this to his dangerous methods.

Rush's ordeal occurred during one of the most important crises of America's early years as a fledgling republic. A yellow fever outbreak struck Philadelphia in 1793 — at the very start of President George Washington's second term — and the American public was terrified.

Although no one knew it at the time, the yellow fever had been brought to America's shores from Cap Français in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). Among the French colonial refugees and their slaves who crowded the ports fleeing from a slave insurrection, there were individuals who had been bitten by mosquitos that carried the yellow fever virus. Mosquitos themselves were also among their ranks, further transmitting the deadly disease with each new bite.

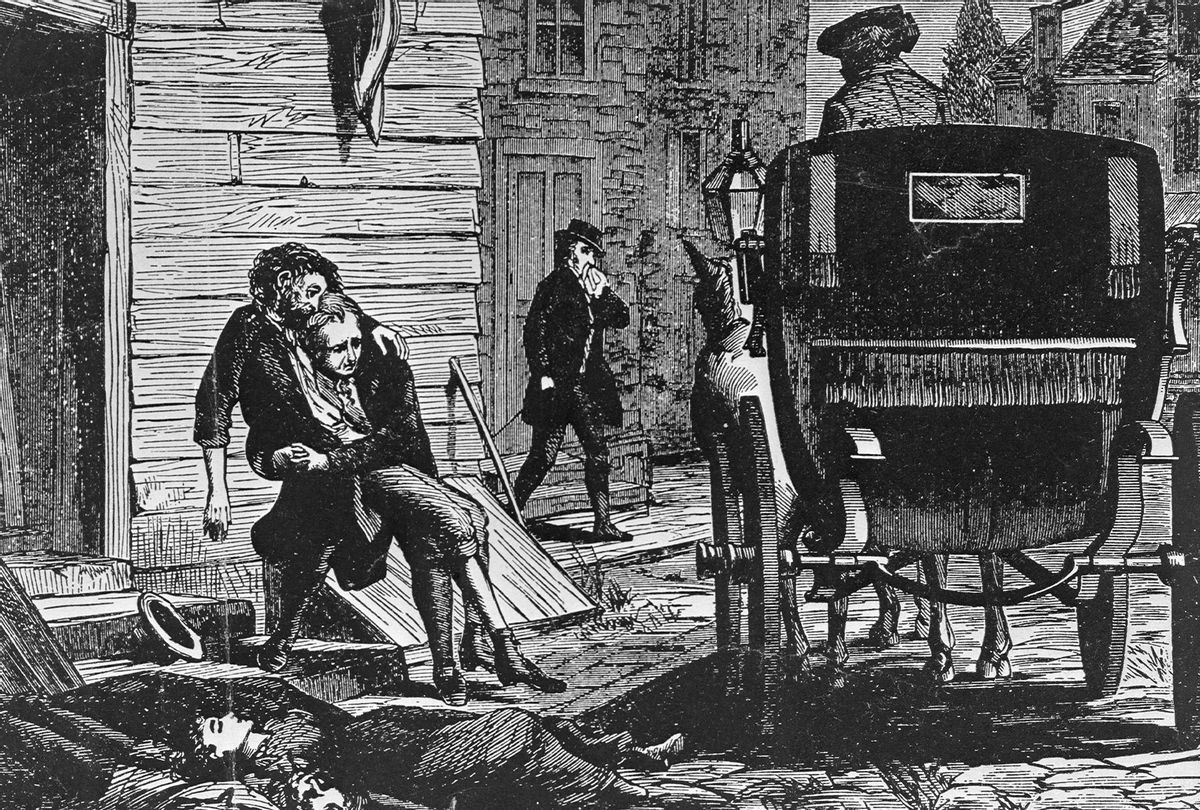

It was Rush himself who recognized the pattern of illnesses and declared that there was an epidemic. Philadelphia had roughly 50,000 residents, most of them clustered in houses near the port. Between late August and early September of that year, the infection spread rapidly through the community, whose panicked residents attempted to flee in order to save their lives.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Not surprisingly, poor Philadelphians had a worse time than their wealthier counterparts. While most of the Common Council fled for their lives, Mayor Matthew Clarkson stayed behind and led efforts to create hospitals, food banks and other facilities to help infected individuals and others who were suffering and had been left behind. The federal government did not have the resources at that time to provide meaningful assistance; what's more, even if it did, the prevailing political philosophy in America was that local governments had to assume the responsibility to help people. Within the narrow parameters allowed him, Clarkson used his political power in an active way to try to help people.

Yet the question of how to help people was not cut and dried. Scientists at this time did not understand the cause of infectious diseases. Some scientists believed that diseases were the result of miasmas, or bad smells such as those produced by dead bodies, biological waste and other disease-carrying substances. Others believed that diseases were transmitted from person to person and had been brought here by ships. Notably, neither side was entirely incorrect: The disease was linked to something people find disgusting (insects) and had been imported. Much like the respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, however, people interpreted existing scientific knowledge in politically convenient ways. The Democratic-Republicans, who deplored cities and wanted a rural America, supported the miasma theory because they could then blame the pandemic on the unhealthy physical climate in cities. Federalists, who were xenophobic, blamed ships because doing so reinforced their anti-immigrant philosophy. The parallel to today's political parties, and who they blame (rightly or wrongly) for various aspects of the pandemic, is striking.

These differing views manifested then, as today, in different policy approaches. Rush was a Democratic-Republican and urged city officials to focus on improving sanitation to make Philadelphia cleaner. The city government rejected Rush's ideas and instead isolated infected patients. The quarantine proved unpopular, as every ship that approached the city underwent mandatory quarantines and sick people were isolated from healthy ones. Taking the lead from Philadelphia's leaders, other cities also imposed controversial quarantine policies. Other major port cities like New York and Baltimore imposed their own quarantines for people and goods coming from Philadelphia. While towns sent food and money to help the infected, many also refused to accept refugees. And there were roughly 20,000 refugees, as Philadelphians fled in droves to get away from the disease.

RELATED: How Washington dealt with a pandemic — in the 18th century

The pandemic also brought out ugly bigotries. Just as hate crimes against Asian Americans soared as President Donald Trump and other political leaders blamed COVID-19 on China, many Americans blamed African Americans during the yellow fever pandemic. Some doctors claimed that black people were immune to the disease because of their race (they actually died at comparable rates to white people), while others singled out black nurses who exploited sick individuals during the crisis while ignoring that many white nurses did the same thing.

When the dust finally settled on the pandemic, 10% of Philadelphia's population had perished from the yellow fever — roughly 5000 people. In the process, it exposed many of the same fissures in American society that have been revealed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is all to say that perhaps Americans haven't changed much. Indeed, Americans in 1793 pointed to similar scapegoats for their pandemic; found similar false cures; and reveled in similarly bad medical practices as their counterparts in the 2020s. Perhaps there is more truth than we'd like to admit in Marx's old maxim that history repeats itself — first as tragedy, then as farce.

Read more on pandemics and history:

Shares