Hubert Humphrey can fairly be described as the Joe Biden of his time, but with one key difference: The Republican candidate who sabotaged U.S. foreign policy and meddled in an overseas conflict in an effort to win his presidential election wound up, well, actually winning it.

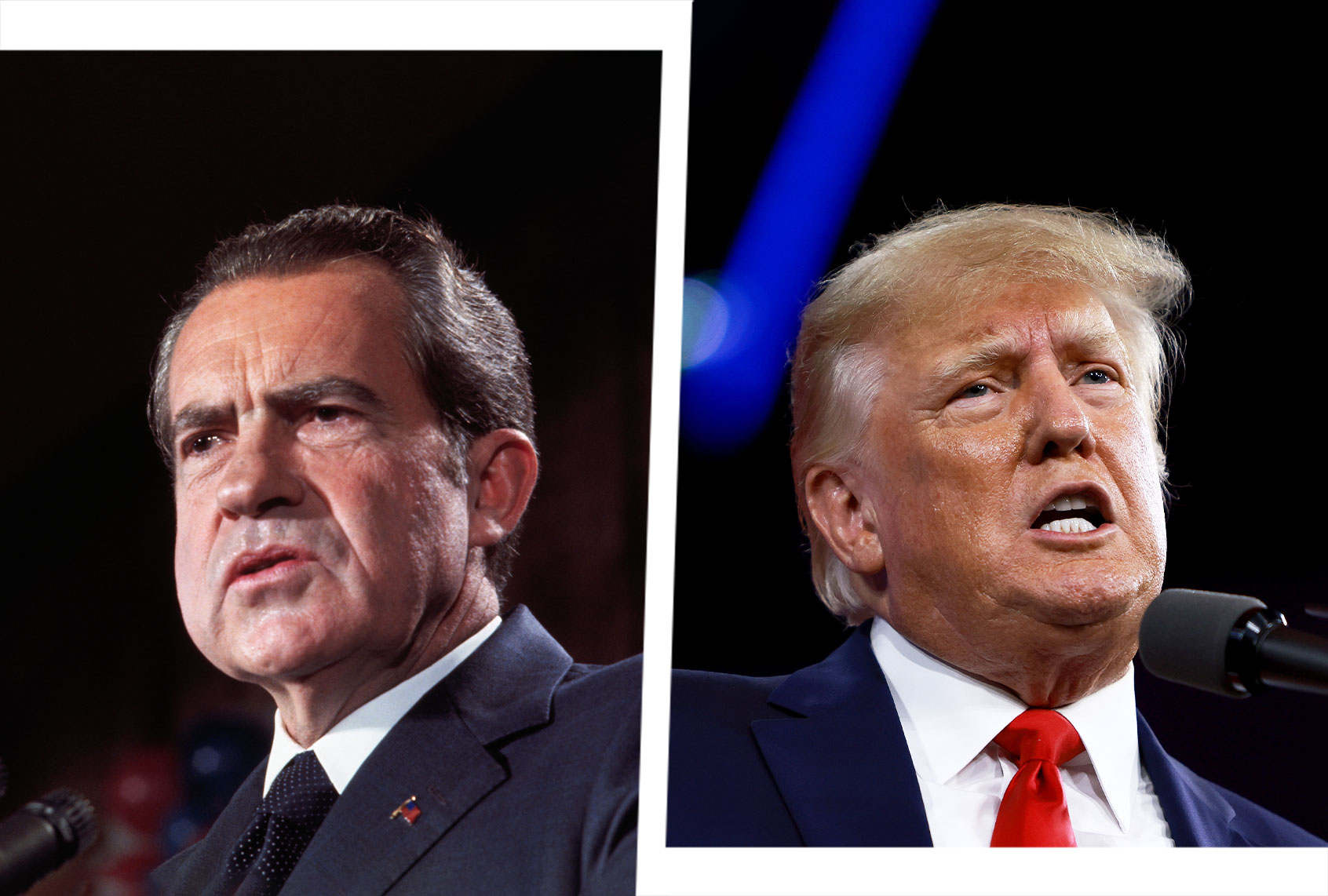

I’m talking about Richard Nixon, who tried to scuttle peace negotiations in Vietnam in 1968, the year he was elected president. I probably don’t need to tell you who ran against Joe Biden and lost in 2020, despite his meritless protests to the contrary —and despite his grotesque meddling in Ukraine.

But let’s get back to Nixon and Humphrey. President Lyndon Johnson originally intended to run again in 1968. (Because he served less than half of John F. Kennedy’s original term after the latter’s assassination, Johnson was in the unique position of being eligible to serve more than eight years as president.) But the Vietnam War had become so unpopular that Johnson was in serious danger of losing the Democratic nomination, and he dropped out during the primaries. After that, the Democratic contest boiled down to a three-way fight between Humphrey — who, as Johnson’s vice president, had largely supported the war — Sen. Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, an antiwar liberal, and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy of New York, JFK’s younger brother.

RELATED: Making history safe again: What Ken Burns gets wrong about Vietnam

As you probably know, that was one of the most tumultuous and tragic years in American history. Kennedy would likely have won the nomination if he hadn’t been assassinated in Los Angeles in June, just two months after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in Memphis. Humphrey didn’t even compete in the primaries, but emerged as the nominee after the infamously violent Democratic convention in Chicago. Alabama Gov. George Wallace ran as a third-party candidate, siphoning off Southern white votes that would otherwise have gone to the Democrats. (Wallace carried five states in the general election; no third-party candidate since then has won any.) In the face of all this turmoil, Humphrey needed massive support from Democrats — even liberals and leftists who didn’t much like him — just to keep Nixon from winning in a blowout.

In fact, Humphrey nearly turned things around, and the eventual election result was closer than many expected. If he had actually won, Sept. 30, 1968 might be remembered as a turning point. Up till then, Humphrey lagged far behind Nixon in polls, largely because he was tied to Johnson’s unpopular war. It’s still not clear whether Humphrey personally agreed with LBJ’s Vietnam policy, but he was a loyal soldier who had never expressed doubts in public. That all changed in a televised speech on Sept. 30, when Humphrey promised that if elected he would halt the bombing of North Vietnam and call for an immediate ceasefire. That served to unite most liberals behind him (although certainly not all), especially given Nixon’s refusal to disclose any details about his alleged peace plan. Nixon’s explanation for this, it must be said, was proto-Trumpian: He argued that unpredictability was a virtue in a president, and he didn’t want the North Vietnamese to gain any advantage by making his plans known in advance.

Humphrey saw a major bounce in his poll numbers, and a historic comeback victory suddenly seemed possible. Nixon, one might imagine, was having flashbacks to his controversial loss to JFK in 1960, one of the closest elections in American history.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Why do I seek to compare Humphrey with Joe Biden? Both men had long careers as powerful senators before becoming vice president, and while the circumstances were entirely different, both were overshadowed by charismatic presidents who welcomed the spotlight. Both were viewed with considerable mistrust by liberals and progressives when they ran for president in their own right (although, in fairness, Humphrey was a genuine liberal with a long record of supporting civil rights and the labor movement, whereas Biden was a lifelong moderate with a decidedly mixed political record). Still, both also benefited from those associations: Humphrey was vice president during a period of ambitious social legislation, and Biden leaned heavily into Barack Obama’s popularity.

And then there’s the fact that Humphrey and Biden both faced unscrupulous political operators and considerable campaign skulduggery. I hardly need to spell out that Biden ran against an incumbent president who tried to coerce a foreign government into launching a phony investigation of Biden and his son, an episode that led all the way to a presidential impeachment and trial in the Senate. Humphrey’s situation was similar but different: His opponent also tried to influence overseas events, in that case by sabotaging peace negotiations to damage Humphrey’s chances of winning.

Nixon, already a master of political dirty tricks — he wasn’t called “Tricky Dick” for nothing — had an ace up his sleeve long before Humphrey delivered his eloquent speech in late September. Through a Chinese-born Republican fundraiser named Anna Chennault, the widow of a prominent World War II general, Nixon had a back channel to the government of South Vietnam, which was effectively a U.S. puppet state. Chennault and others, acting on the Nixon campaign’s behalf, urged the South Vietnamese government to boycott peace talks with the Johnson administration. Their argument, before and after Humphrey’s big speech, was that Nixon was likely to win the election and would offer the South Vietnamese regime a better deal.

Johnson, as it happened, knew all about this and viewed Nixon’s actions as “treason” — but had no obvious way to expose Nixon without revealing that the administration had been spying on a political opponent. The best LBJ could do was to try to give Humphrey a boost — despite rising tension between them — by announcing a halt in the bombing of North Vietnam on Oct. 31, just days before the presidential election.

That was too little, too late: Nixon won the election and all hope of Vietnam peace talks in the near term collapsed. The war continued for several more years, until the U.S. military finally withdrew in 1973 and South Vietnam collapsed in 1975. There is no way to know how many people died because of the thwarted negotiations, but at the time Johnson estimated that South Vietnam was “killing four or five hundred every day waiting on Nixon.”

We’re not talking about accusations or allegations here. All of that has been extensively documented through papers and tapes, personal accounts and government records. Rumors appeared in the press at the time and the whole affair was an open secret in Washington. But it remains little known today, which can also be said about Donald Trump’s threats to withhold $391 million in military aid from Ukraine, already allocated by Congress, unless the Kyiv government announced a spurious criminal investigation into Hunter Biden’s business dealings. As we now know all too well, the threat that Russia posed to Ukraine’s sovereignty was genuine.

Nixon’s unpunished chicanery meant that a misbegotten foreign war dragged on for years, costing thousands of lives. There is no visible direct connection between Trump’s attempted extortion of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and Vladimir Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine three years later. But those events are linked, at the very least, through Trump’s curious relationship with Putin, whom he continued to praise right up to the day of the invasion. How future historians may view the period leading up to the Ukraine conflict is of course impossible to say. Given the climate of increasing global tension and the rising danger of nuclear war, let’s hope we’re still here to find out.

Read more on the Vietnam War and American history: