In the first season of "Full House," the Tanner family, led by the late Bob Saget as Danny Tanner, is still reeling from the recent loss of wife and mother, Pam. By the ninth episode, Thanksgiving has come to San Francisco and the family is confronted with the fact that it's the first holiday meal without Pam — and that they owe it to her memory to make it a special one for the girls.

Initially, this doesn't seem like a major problem; Danny's mom is set to fly in from Tacoma and cook for the family. But, of course, it wouldn't be a sitcom if there wasn't an unforeseen snow storm that tanks even the most well-placed holiday plans. When it becomes apparent that Danny's mom won't, in fact, be able to make her flight, Joey (Dave Coulier) has a solution.

"It's no problem, we'll make that seven-course meal ourselves," he said. "How, you ask? The miracle…of Thanksgiving."

I remember even as a pre-teen being a little exasperated by the assertion that a multi-course Thanksgiving dinner comes together through the power of some kind of intangible holiday magic. I'd both watched enough "Food Network," as well as my own mother and grandmother cooking in the kitchen year after year, to know that was absolutely not the case. The holiday magic to which Joey is most likely referring is the unseen domestic labor that tends to fall to one or two specific family members (historically and socially, often women).

And indeed, DJ (the now-controversial Candace Cameron Bure), the eldest daughter at ten years old, decides to step into her mom's shoes and take charge of Thanksgiving dinner. It, predictably, goes a bit off the rails — there's a blackened turkey and a ruined pumpkin pie — but regardless, the episode in its entirety is a real crystallization of the concept of domesticity as a performance.

To be clear, performing domesticity isn't necessarily a bad thing, and I'm not the first person to liken a good, or at least memorable, dinner to theatre. Michael J. Fox, actually, once astutely pointed out, "The oldest form of theater is the dinner table. It's got five or six people, new show every night, same players. Good ensemble; the people have worked together a lot."

"The oldest form of theater is the dinner table. It's got five or six people, new show every night, same players. Good ensemble; the people have worked together a lot."

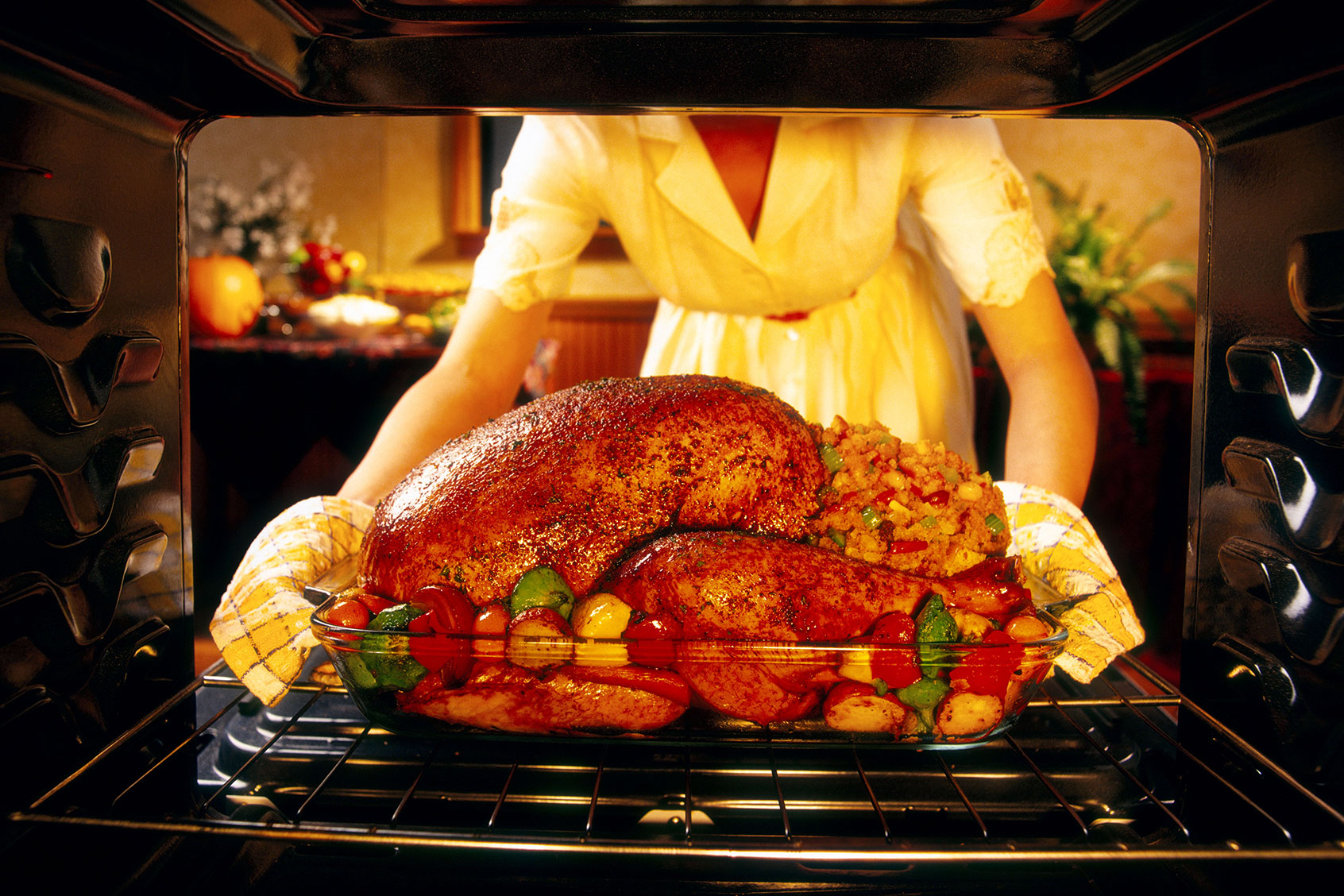

Just as everyone in a restaurant kitchen has their roles to play, from saucier to sommelier, so too are roles assigned at holiday dinner. In the case of DJ, she picked up the role of hostess, which comes with its own specific expectations. If you've ever hosted Thanksgiving, you know them well: a golden-brown turkey with the mythical, appropriate ratio of white to dark meat so everyone can eat according to their preferences; sides that are somehow both traditional and novel; at least two desserts — most likely pumpkin pie and something for those who detest pumpkin pie.

Want more great food writing and recipes? Subscribe to Salon Food's newsletter, The Bite.

Perhaps you're gearing up to step back into that role again later this week.

And just perhaps, you're also dreading it.

I mean, there's certainly enough pop culture fodder out there — from "Full House" to "Friends" to "Frasier" —about the desire to push against the confines of holiday meal preparation and execution. This is especially tempting given the way so much cooking advice surrounding Thanksgiving entertaining positions it as practically a matter of life and death, ruled by spreadsheets, countdown clocks and that profound existential dread that comes when faced with the expectations surrounding crafting your own personal platonic ideal of the holiday meal.

If that's you, may I offer one piece of entertaining advice? If entertaining is a domestic performance, then at least let Thanksgiving dinner be camp.

In her landmark essay "Notes on 'Camp,'" Susan Sontag defines the aesthetic as such: "artifice, frivolity, naïve middle-class pretentiousness and shocking excess." Based on that alone, while Thanksgiving may not be the campiest holiday — I'm personally torn over which holds that distinction — it's definitely up there.

And much like recognizing domesticity as a performance isn't inherently bad, neither is camp, though many people have come to regard the term as a synonym for kitsch or tackiness. Sontag rather describes it as "a sensibility that revels in artifice, stylization, theatricalization, irony, playfulness, and exaggeration rather than content."

Much like recognizing domesticity as a performance isn't inherently bad, neither is camp, though many people have come to regard the term as a synonym for kitsch or tackiness.

Some of the most beloved movies are regarded as camp classics because of those attributes; think of "Death Becomes Her," "Rocky Horror Picture Show" and "Clue."

Speaking of "Clue," I recently was texting with a friend of mine from college who is now an actor. Typically they operate sort of within the realm of Shakespearean roles, but their first role since coming back after pandemic lockdowns was in a community theatre production of "Clue."

I messaged asking how they enjoyed being in a show that was so different from what they normally do, and they quickly replied: "I mean, it's camp and camp equals freedom as an actor."

Camp in the context of Thanksgiving could look like a lot of different things. One could nod to camp icon "Auntie Mame" and serve fabulous fishbowl cocktails the size of their guests' heads accompanied with the tiniest turkey finger sandwiches they've ever seen. One could start with the traditional Thanksgiving spread and subvert it in some way, a la another more contemporary icon, Amy Sedaris (seriously, her book "I Like You: Hospitality Under the Influence" is a textbook in terms of examining the intersection of camp aesthetics and home entertaining).

That's the beautiful thing about camp. It doesn't have to look like or operate as one specific thing. It's not a set of static aesthetic principles. It's bolstered by context and malleable over time; that's why certain films or actors who were regarded as critical flops can still achieve camp classic status in due time.

The point is, you don't have to take it all so seriously. If traditional Thanksgiving dinners have left you feeling like a Shakespearean actor confined to a specific role — one that is laden with centuries of expectations — consider changing roles, or at least how you approach yours at the holiday table. Camp equals freedom as an actor. I believe it can provide the same in the kitchen.