Sometimes life’s breath catches in time’s throat. Those fortunate enough to float inside one of these moments, with the air still and humming, don’t soon forget it. Religious folks have words for such spasmodic departures from the everyday, like beatitude, nirvana, ecstasy. Bliss.

Using the same descriptions for carnal matters tends to irritate the pious, but it isn’t improper in the least. They encapsulate human states that are simultaneously natural and unbelievable, pressing fingers against the skin of some cosmic chamber we trust to exist but can’t fully access in this life.

So we chase them, each in our way. One way of considering the musical legacy of D’Angelo, who died Tuesday, Oct. 14, of pancreatic cancer, is that he surrendered to the pursuit of that electric state, channeling what he found and emerging when he saw fit to share the immensity it inspired.

Producing three critically acclaimed, groundbreaking works laden with verses and harmonies containing the power to steal our breath after countless listens is more than most musicians achieve in a lifetime.

“I just want to take you with me, to secret rooms in the mansions of my mind,” he sang on the rapturous single “Another Life.” “Shower you with all that you need . . . take my hand, I swear I’ll take my time…”

To the millions enraptured with his music and hypnotic voice, the multiple Grammy winner’s infrequent appearances added to his legend. His first full-length release, “Brown Sugar,” dropped in 1995. Five years would pass before its follow-up, “Voodoo,” catapulted him to a level of fame that made him retreat from the public until 2014, when he returned with the more politically infused funk-fest of “Black Messiah.”

(Shahar Azran/Getty Images) D’Angelo performs at The Apollo Theater on February 27, 2021 in New York City.

Three albums produced over three decades may seem frustratingly light to a generation of musicians and fans primed to define success by prolific output. And yet, producing three critically acclaimed, groundbreaking works laden with verses and harmonies containing the power to steal our breath after countless listens is more than most musicians achieve in a lifetime.

Frequent collaborator Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson once called D’Angelo the last pure singer on Earth. Alan “Pops” Leeds, the tour manager who previously worked with James Brown and Prince, described him as the kind of performer that comes along once every other generation.

“Against the grain of bland modern R&B, D’Angelo preserved the Gospel essence of early soul music, mixing it with every other genre of Black music without ever leaving the church,” Leeds said in an Oct. 14 Facebook tribute. “… After one of our shows, you FELT like you’d been to church. Good church!”

D’Angelo died at 51, more than a decade after his last album, and months after his former partner Angie Stone, with whom he shared a son, was killed in a car crash. Raphael Saadiq, his co-producer on “Voodoo,” had been working with him on a fourth album. That note of hope also ends Carine Bijlsma’s 2019 documentary about him, “Devil’s Pie.”

But loving D’Angelo’s musicianship is a commitment to yearning and understanding the mercurial nature of the artistic process — not to mention the slow process of this particular artist. His perfectionism stalled him out for years, but his resentment of the music business’ commercial pressures also took its toll.

Born Michael Eugene Archer in Virginia, D’Angelo was an artist in the tradition of the soul greats like Marvin Gaye and Al Green, but also Otis Redding, the Isley Brothers and Sly Stone.

Like many who defined soul, D’Angelo honed his talent in the church. The son of a Pentecostal preacher, he revealed in a 2014 GQ interview with Amy Wallace that he taught himself to play Earth, Wind & Fire‘s “Boogie Wonderland” at the age of 4. His father disapproved of him playing any music that wasn’t in service of the Lord, so after his parents divorced and D’Angelo went to live with his mother, he followed the encouragement of his grandmother, whose views on sacred and secular music were more liberal.

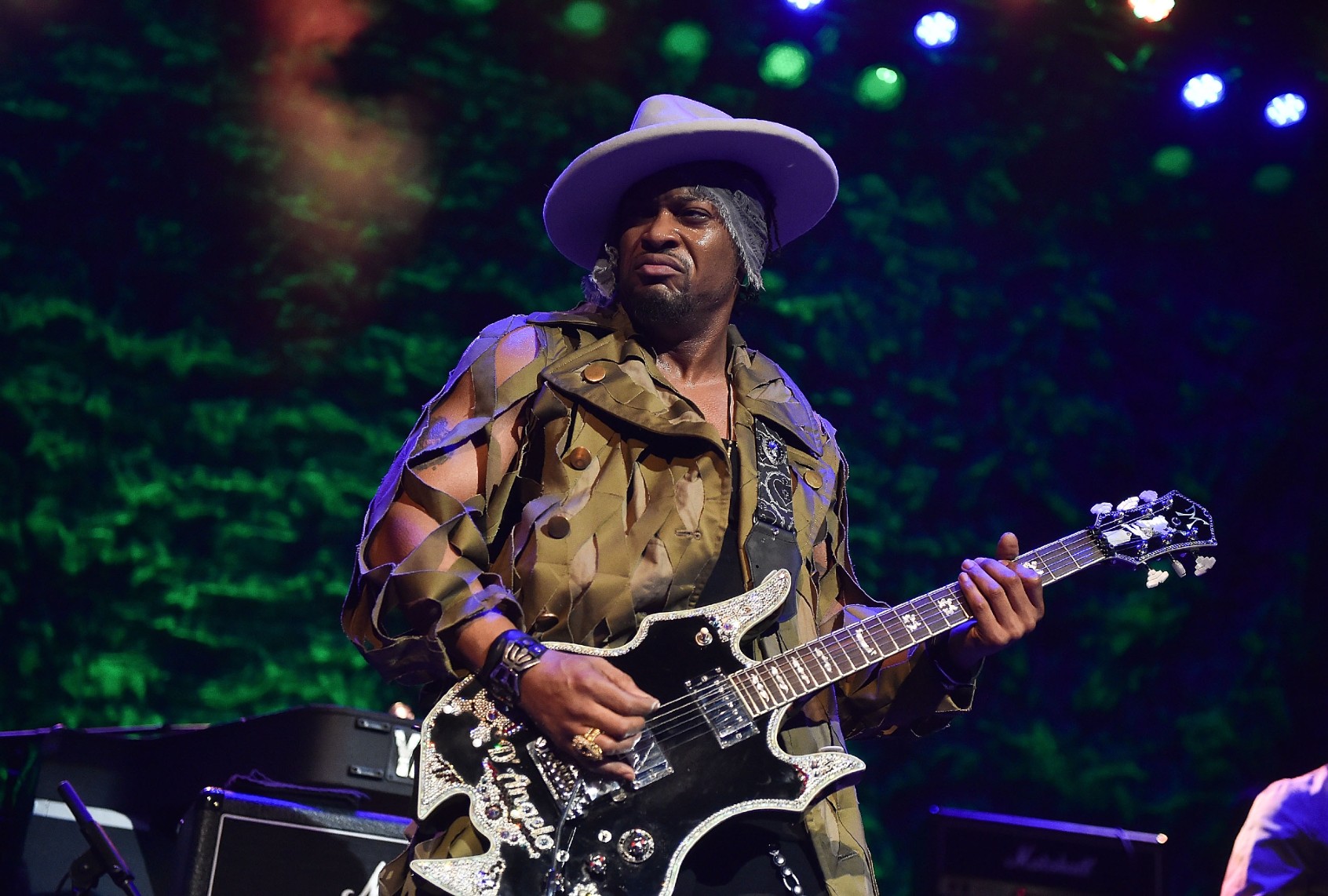

(Paras Griffin/Getty Images) D’Angelo performs onstage at The Tabernacle on June 14, 2015 in Atlanta, Georgia.

Bringing that duality introduced a style that was both fresh and ancestral into a pop music scene still defined by the electronic splash of New Jack Swing artists like Boyz II Men, Saadiq’s group Tony! Toni! Toné! and Keith Sweat. The title track of “Brown Sugar,” like the rest of the album, is at once a throwback to early Prince (one of D’Angelo’s “Yodas,” as he and Questlove called their influences) and a deep, reverent bow to the old school.

D’Angelo’s co-writer and producer, Ali Shaheed Muhammad of A Tribe Called Quest, merges the DJs signature rhythmic heartbeat with the kind of organ riff that uplifts meditative moments in church, but it’s the singer’s falsetto and the sly flirtation curling through the refrain – “I want some of your brown sugar” – that blurs the line between romance and something more illicit. “Brown Sugar” sounds like it’s about a girl, but it’s a love song in the tradition of Rick James’ “Mary Jane.”

“Voodoo,” though, announced D’Angelo as the inheritor of a lineage stretching back centuries, opening with ceremonial drums and fatback bass thump, traveling through the raw verbal dirty talk of Wu-Tang Clan’s Method Man and Redman on “Left and Right.” There’s an apocryphal story of a critic likening a Jimi Hendrix performance to “listening to heavy metal falling from the sky”; the guitar riffs throughout “Voodoo” pay homage to that rock god by refining the platinum left at that crash site and floating it back to heaven.

We need your help to stay independent

D’Angelo’s “Untitled (How Does It Feel),” the second to last track on 2000’s “Voodoo,” is the song that made him internationally famous. Sonically and lyrically, “Untitled” is a masterpiece in seduction, progressing from Questlove’s messy whisper of a beat to a single bass note, then rolling into a D-chord on the piano that lands like a caress a new lover would withhold to sharpen the appetite.

Once Saadiq’s guitar grinds in, the song blossoms into a harmonious striptease, deliciously shocking the listener when the singer drops the first verse’s coy entreaties to make it filthily plain what he wants in the second.

But it’s D’Angelo’s soaring vocals that transmute the molten instrumental throbbing into a transcendent buzz, achieved through multi-track vocal layers and a vacillation between climactic reverb roars and serene breaks. Like exhausted lovers relaxing on their pillows before going at it again. Or an ecstatic believer collapsing after the Holy Spirit releases them.

Fueling our mass mourning’s ache is a lack of knowing who will ignite the next blaze like the one D’Angelo sparked.

D’Angelo cultivated a space between himself and the audience, and the few extensive profiles he sat for closed that distance. Bijlsma’s documentary is one of them; it isn’t commercially available, although it’s easily found on the Internet. It captures the sensation of being in his orbit as opposed to focusing on any explanations of all that occurred between “Voodoo” and “Black Messiah.” During those years, the singer struggled with addiction and depression, making national headlines in 2005 when he crashed his Hummer while high on cocaine and drunk.

Another is that GQ interview, which provides emotional insights into what it was like for an emerging artist listed among several defining the neo soul subgenre, including Jill Scott, Erykah Badu, Lauryn Hill and Stone, to be dubbed its divine standard-bearer.

In his Village Voice review of the artist’s live show at Radio City Music Hall in 2000, Robert Thomas Christgau summarized his first deep drink of D’Angelo’s musical libation by saying, “He was R&B Jesus, and I’m a believer.” So were many music lovers.

By then, it wasn’t the singer’s talent drawing worshippers to musical temples around the world. His chiseled body, stripped to his glistening skin, was what sold tickets and shot “Voodoo” to platinum status, courtesy of the “Untitled” video, a one-shot, minimalist wonder co-directed by Paul Hunter and D’Angelo’s manager Dominique Trenier.

If you were around to experience its debut on MTV and BET, you may remember how it stopped time for you, too. The visual of a camera slowly licking D’Angelo from his cornrows to the edge of “down there” as the singer mouthed the lyrics, smiled, flexed his muscles and danced, was the kind of foreplay the legion of heavy metal babes and scantily clad video honeys that came before it could not match. This was a suggestion that women, and men, took D’Angelo up on.

Many years later, and long after recoiling and hiding from the screaming hordes at his concerts demanding, “Take it off! Take it off!” he explained to GQ that he was actually thinking about his grandmother’s cooking. Hunter seconds that, telling Wallace that he was after evoking a sense of intimacy.

“It’s so true: We talked about the Holy Ghost and the church before that take,” D’Angelo said. “The veil is the nudity and the sexuality. But what they’re really getting is the spirit.”

Start your day with essential news from Salon.

Sign up for our free morning newsletter, Crash Course.

If spirit is an invisible bridge between the flesh that eventually fails and the infinite contained within that vessel, this revised reading clothes “Untitled” in a new meaning. It will always be a melter of a slow jam, but its intention is in those parentheses – to be in the sensation of aliveness he’s created.

After a performance that Bijlsma captures in “Devil’s Pie,” he talks about how money can never replenish what artists leave on the stage.

So, he asks, what replenishes the soul? “Because I don’t want to feed myself religion. I want to feed myself God, right? So how do you get past all the ritual and the politics and just get to source? . . . I think God is inside all of us, but it’s about clearing away all of the distractions and all of the roadblocks.”

Fueling our mass mourning’s ache is a lack of knowing who will ignite the next blaze like the one D’Angelo sparked, forging the sensual and the spiritual, with passion’s hand clasping its mate in prayer. But at least we know that in the short time he had with us, D’Angelo left a roadmap. We just have to open ourselves to feeling our way.

Read more

about this topic