From their poorly-timed coming out statements to convoluted, self-congratulatory confessions to mea culpas with bonus pizza dough cinnamon roll recipes, a common denominator among public figures recently revealed to have a history of bad behavior is that they’re also pretty godawful at apologizing.

The past several months have brought a deluge of accusations and revelations against a host of powerful men, charges ranging from unprofessional and sexist comments to far more serious, criminal acts. But with their entire futures on the line, why then have so many of these politicians and celebrities failed so spectacularly at even going through the motions of public atonement?

In the quest to understand what’s going wrong here, Salon turned to Los Angeles public relations executive Danny Deraney. In addition to traditional PR, Deraney has in his career done crisis PR for a variety of clients, so he knows a lot about what good damage control should look like. Via phone recently, he spoke about the essential elements of keeping a bad situation from getting worse.

Do people come to you when they’re in crisis, or is it more that you get the “Uh-oh, the Times is working on the story” call from people you’ve already worked with?

It’s both. The majority of my business, thankfully, is word of mouth. I’m not an ambulance chaser. If I see someone is in trouble, I don’t go out of my way unless I know something about that person or I know something about a situation and I’ll know they’ll be vindicated. But I’m not going out looking for something that doesn’t exist.

A lot of people associate me with working with the Kerri Kasem situation, or the “Dog’s Purpose” story. Whether it’s crisis or something else, they want someone who’s going to clearly go to bat for them.

Until recently, my idea of crisis management was, “I made a mistake. I’ve caused pain. I am getting help. I shouldn’t have yelled at that person on the set on the set of my movie.” But now, we’re talking about things that go on mostly in private that are very, very hard to substantiate unless you have multiple accusers — which a lot of these stories now do — and I don’t think there is a redemptive arc. How does someone work with that now?

I think your most important ally in crisis communication is time. . . . You need to use that as your ally. Use what you have to your advantage. Do not rush it or make a harsh statement.

It’s hard when you really want to react. You want so badly to say something, and if you’re a fan of one of these people, you want them to say something. But time is your biggest strength, so people can think with a clear head and not with some immediate gut reaction.

Depending on the situation, you want to be sure that you have all your ducks in [a] row and you want to be correct. If you are a celebrity, you have your public; you have your fans; you have people who want to hear from you. You want to make sure that you’re right, whether you are proving your innocence or whether you are guilty of something and want to make sure that you are owning up to what you have done.

With particular regard to the sexual harassment, is anyone telling these guys how badly they are doing this? Everyone I know, certainly every woman I know, is just waiting for a single not crappy apology. Danny, why? It seems like people maybe are bad at this.

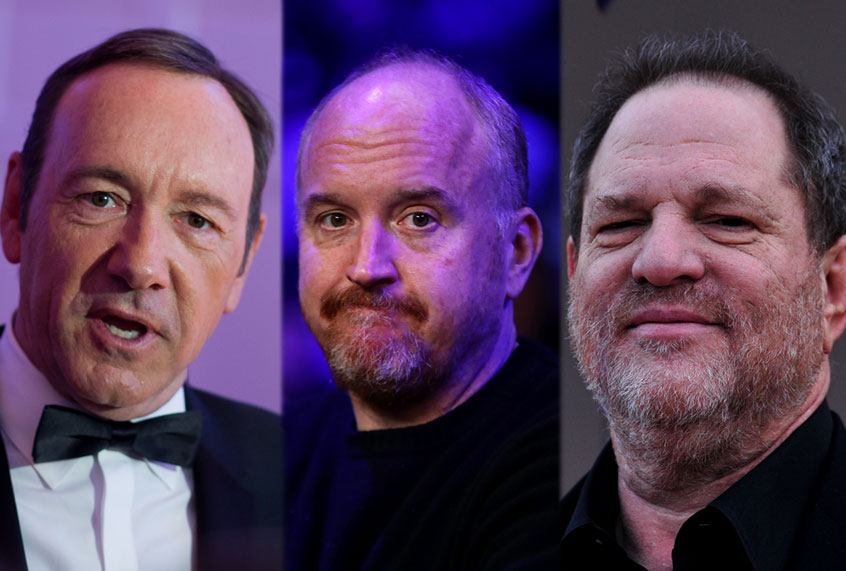

I am sometimes dumbfounded by some of these statements that I’m seeing. When I saw that the whole Kevin Spacey thing — what the heck?

I’m looking at these statements and some were okay, but some, the words in there just made no sense. With Kevin Spacey’s, it was that one thing had nothing to do with the other. Or Louis C.K. not understanding his position of power. Maybe there’s no publicist helping them craft it. Maybe it’s just the manager. Maybe it’s just, “This is my statement and I’m going to hand it to one person because I know them and trust them.” I don’t know. I’m not in there with them, but for me, regardless of the situation, I want this to come from you. You need to be honest. You need to own up to everything in your statement. When you look at some of these statements, you just shake your head and you’re going, “Why? What do we need to release that? What would make you say that?”

Your job is to protect your client. In these cases, again, I can’t speak for them because I don’t know what was said. I don’t know who was involved. But I look at these statements and I hit my head all the time and I wonder how it’s happening.

The Harvey Weinstein statement was also horrible. “Oh, it was a different time.” I have really yet to see a statement that makes me believe, “I think you get it.” Is that just the ego of these personalities? Is it just that they honestly don’t think that they need to do better? Is it that they are surrounding themselves with sycophants who don’t know how to tell them, “What you’ve just presented me with is garbage?” I’m really confused because if I had to work with these people, I would say, you have to do better.

I think it’s a little bit of everything, to be honest, when you are given the keys to the kingdom and you’re constantly being told how wonderful you are and you’re surrounded by yes-people all the time. The last two years has been so evident of that. When you’re surrounded by people who do nothing but lavish you and love you all the time — and this is by no means an excuse — your ego is going to be in a place where it’s probably never been before. When you are in that position of power, I hope not everybody, but obviously you tend to feel you can do whatever you want and get away with it. Now, we’re finding out that you can’t get away with it.

Let’s say you had a client and let’s say it is sexual harassment. Obviously, that’s a big spectrum. But let’s say you had a client who’s said, “Oh my God, I have to tell you. Some stuff is going to come out. It was a period in my life where it was after my divorce and I was drinking a lot and I made a lot of mistakes.” What would you tell that person to do to do right that is not being done in these stories? Or would you just say, “I can’t handle these guys. They’re gross”?

I think it depends on what they’ve done. If you’re talking about, “I molested a 15-year-old child,” I’m not going there. There are stories where I go, “No, I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to protect you. Even though you were drunk one night or whatever, I’m not going to do it.” Publicists need to realize you have your own brand to protect. You have just as much right to protect yourself as you do for so-and-so famous person. If you’re an ambulance chaser, you’re not going to care who you take. If you have credibility, you’re not going to put yourself in that position.

Now, if someone is going to come to me, it just depends on the situation. If somebody cheated, that kind of stuff happens. I think we as a society forgive things like that. We tend to rail at somebody who might have done that once, but other people in higher positions of power, we don’t care about. How many different presidents have had mistresses, but we brought them back in office?

Let’s use that as an example. You got caught in a consensual adult indiscretion. You caused pain to your family, maybe you disappointed your fans or your constituents. That seems like the sort of thing someone can crawl their way out of.

I agree. Yes.

How would one do that? How would you advise someone in that kind of crisis management? Because it also can be a career wrecker, right?

It can be. I think the first people you have to talk to are the most important people you’ve hurt. The fans and everybody else are completely secondary. Really, the only people you owe a response to are your loved ones. If it’s a situation like that, you talk to your spouse, you talk to your kids.

If word gets out or something like that, the most important thing is [deciding] what you want to reveal. If your career is suffering because of something that you did, you might want to come out and talk to somebody about it. If there are no ramifications, then it’s a private matter that should be kept that way and your audience should accept that, depending on the severity of the situation. “I’m in a rough patch right now with my spouse, with whomever. We’re dealing with this internally. I hope you understand this is private matter that we want to take care of.” Perfect. You don’t have to go into a whole into an apology tour. It’s not like a situation where for 20 years I’ve been lying that I haven’t been taking steroids, but guess what, I can’t lie anymore. That’s a completely different story. Use time. Unless you see your career being affected by it, that is when you address it and you address that with, “I’m sorry for the pain I’ve caused and that it’s causing for you to lose your trust in me.” There are two things: time and the upfront honesty from the get go. It’s all those adage to use, but it’s tried and true because it works.

It seems also very important and very strategic to find out if there is an interviewer who can speak to your character with credibility, or to speak to your journey back to learning your lessons and trying to do better.

Yeah, you set up an interview with someone, and you want integrity and someone who’s not going to let you off easy, but at the same time someone who’s not looking for a story that doesn’t exist. You want to have someone who you can trust. You want all questions to be asked. I don’t want my client going on somewhere where they’re going to be insulted. I want a discussion. I want the truth to be told. I don’t want some insinuation of something that didn’t happen to take place. It’s knowing who the journalist is and what they’re passionate about that will help a topic that needs some light shedding on it. These are important issues — whether it’s with a crisis situation or any situation — to know the journalist is going to do a good job in handling your client, but also really give that extra boost to a story that needs to be told.

What you’re talking about with crisis management is, read the room. Do your homework. Know where you’re going and know who you want to tell this story with and know who it is you need to really be addressing in that message. Is it your disappointed fans? Is it women? Is it, I said something insensitive against the particular group? How do I then speak in a language that says, “I get it. I understand it”?

This kind of behavior has endured for decades because of this wall of silence. The amount of complicit behavior around it is staggering. I think that part of why this dam has burst is in response to what we’re looking at in this administration and this strong sense of “we’re done.” The consequences of speaking up no longer seem as scary as they once did because the consequences of not speaking up have become so much more painful and so much more profound.

I think women now thankfully are finding that voice. Men too, Terry Crews for instance. People are finding their voice finally. I think what you’re seeing now is the momentum of that all changing, whether it’s all this executives being fired and let go, all these anchors being let go from their jobs, hopefully being replaced by more women, by minorities and so forth. I think it’s the beginning of something that is so huge right now that in my opinion, there is no turning back.

With more people willing to speak up to erase that toxic masculinity that we all grow up in, men and women, I really believe that it’s starting to lessen, even though it still exists. You’re going to see more men apologizing and maybe more men finding their sensitive side. You’re finding men willing to speak out about that and hopefully we’ll keep seeing it, not because of a preventive strike to what they are doing, but to say, “Hey, look, I’m here to support you in your cause. I messed up along the way. This is how I’m going to better. What are you going to do next?”

That’s what I’d advise anyone to do. If you have something you’re unsure of — and you could be completely clean — but if you think you’ve done something, be a man and say something. Make a tweet and say, “Look, I wasn’t the best towards women and I feel horrible about it. Let’s make a change together as a society.”

I really also question in a lot of these cases whether for some of these guys, if anyone had said, “Maybe we should get a woman to tell us what would sound good here. But maybe we should actually ask women and get their feedback on what would make this right or what would make this better.”

Yeah. Ask a woman. Do you have a panel? Have women on the panel. If you’re talking about civil rights, you’re talking about minority rights; it shouldn’t be a panel of all white people. You need to ask women why this is wrong, how you can be better. Get their perspective to invigorate these conversations so it doesn’t happen any more. I always say, make yourself better than you were the day before, always. Have those dialogues, keep open, so you don’t do it again.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.