What does the nickname Lolita conjure up in your mind? Does the title of Vladimir Nabokov's infamous, acclaimed 1955 novel make you think of a girl, dressed perhaps in the manner of Britney, circa "...Baby One More Time"? Do you picture a coy seductress? It's OK; me too. The cultural conditioning runs deep. Even those of us who love Nabokov's haunting fictional tale of a child and the pedophile who becomes obsessed with her know how eroticized poor Dolores Haze has become. Yet Dolly's story remains unmistakably a tragedy — just like that of the real girl who served as an inspiration.

In Camden, New Jersey, in 1948, 11-year-old Florence Sally Horner was approached by a man named Frank La Salle, who told her he worked for the FBI. She didn't come home for 21 months. In the interim, he took her all across the country, sexually abusing her while telling people she was his daughter. Her suffering didn't end after La Salle was arrested. And seven years later, Humbert Humbert would ask himself, "Had I done to Dolly, perhaps, what Frank Lasalle, a fifty-year-old mechanic, had done to eleven-year-old Sally Horner in 1948?"

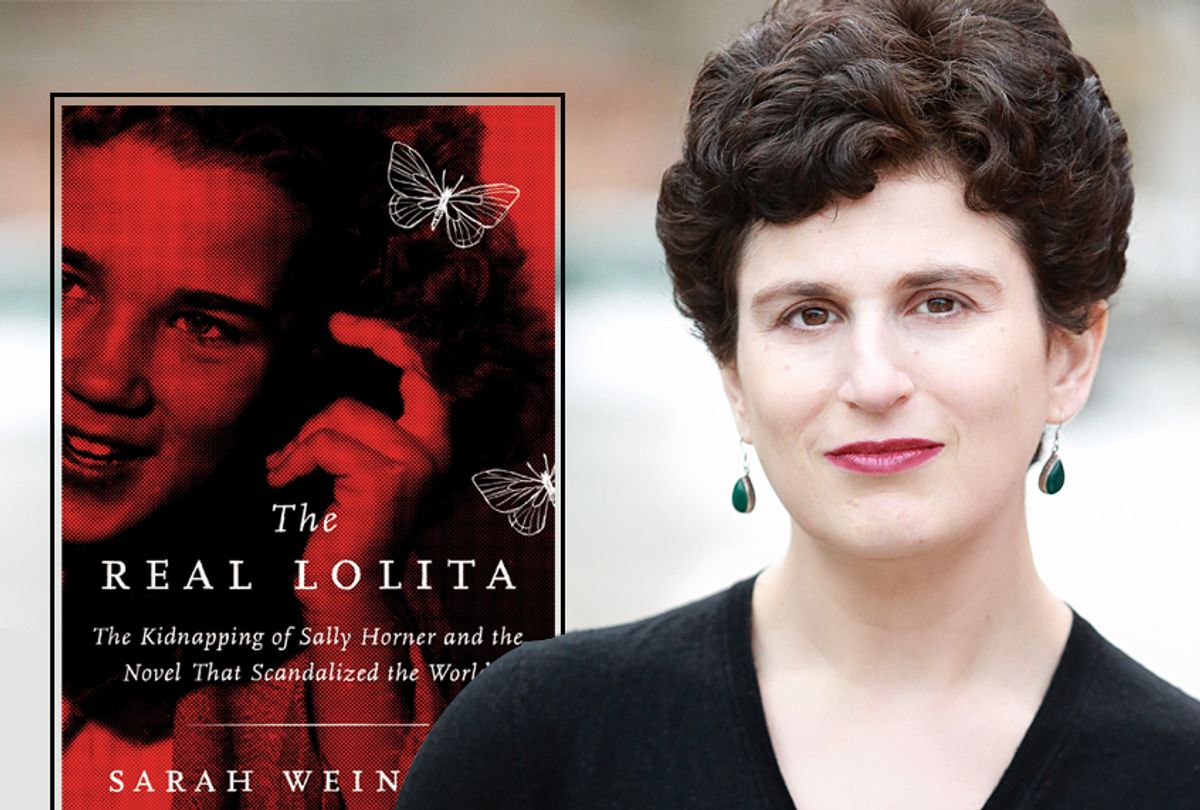

In "The Real Lolita: The Kidnapping of Sally Horner and the Novel that Scandalized the World," journalist Sarah Weinman pulls off a remarkable double feat — she's written a fascinating work that's both a literary history and a true crime story. And at the heart of it is an enigmatic girl whose experience has finally been given its due.

"I never really thought of this book as one or the other," Weinman told Salon. "It was always in my mind that they had to be intertwined, because as much as Sally Horner's story is so important and does stand on its own, I've seen other people treat this as just a strictly true crime story. From the first moment that I started working on this project, I always thought of it as, this is the real-life case that inspired the novel 'Lolita,' and it was always extraordinarily intertwined."

Like other survivors of famous crimes, it does seem apparent that Horner wanted an identity outside of victim — and the stigma that went along with it. Colleen Stan was 20 years old when was she abducted and held captive, yet the now-61-year-old is still forever known as "the girl in the box." Elizabeth Smart's nine months in captivity have defined her persona for the ensuing 15 years.

Smart has generously been able to turn her experience into advocacy for others. "I'm proud of being a survivor," Smart told Salon last year. "I'm still here. I'm not giving up."

But after his seven-year long abduction and sexual abuse ordeal, Steven Stayner returned to his family and wondered, "Why doesn’t my dad hug me anymore?" Stayner died in a motorcycle accident when he was 24. His older brother Cary, who later claimed that his family's ordeal made him feel "neglected," is a convicted serial killer.

Weinman recalls a photograph she has of Sally and her mother Ella with Camden County Prosecutor Mitchell Cohen, taken shortly after Frank La Salle's sentencing. "It was at that meeting that Cohen told Sally and her mother, 'You're better off leaving Camden, changing your names and starting life over again,'" she says. But Sally and Ella stayed.

"They went back to the house where Sally grew up and she went back to the school where she had been before La Salle took her away, before she was kidnapped," Weinman explained. "She then had to live in the same community with the same people who knew exactly what had happened to her. It wasn’t just because it was flashed all over all these national and local newspapers. It was a community thing, and people didn’t interpret it as, 'Oh, she was raped or sexually abused.' They said, 'Oh, she had sex with this guy. Therefore she must be a slut.'"

"It still boils my blood," she added. "That was the attitude and in a lot of cases that’s still the attitude. We still will have to fight against this and tear that idea down."

We don't have to look far for contemporary examples of what Weinman is talking about — just look at the conflicting narratives around R. Kelly. Accusations against the R&B star of sexual abuse of young girls have persisted for two decades. Yet that has barely made a dent in his popularity, while accusers have been painted as "hopping on the money train" after having "consensual" relationships with him.

"If you studied or pay attention to crime as long as I have, things seem a lot starker and more simple," Weinman said. "Whereas other people are just like, 'But I don’t understand how this works.' It’s really not that difficult to get your head around if you have the framework to work this through. I think that’s also why true crime has had this resurgence, because the world is so seemingly unknowable and crime narratives help us to grapple with what's going on. It makes complex things a little bit easier to understand in terms of human behavior."

READ MORE: What to read next: 5 recommended books for back to school season

That fascination, I suggest to her, also feels rooted in our deepest fears, and the nagging question, what would I do if it were me?

"That’s always been the primary driver for why I've been interested in crime stories, be they real crime or crime fiction," she said. "I've always just wanted to get at 'Why?' and understand extreme behavior. There's nothing more extreme than one person killing somebody else, especially when a man kills a woman in a particularly violent and awful fashion. Why would this behavior happen? What produces this interaction that someone would go over the edge like that?"

"Or in the case of psychopath, they aren’t necessarily going over the edge," she continued. "They're acting out of a particular compulsion or signature, and that’s what produces the behavior that they end up doing."

That curiosity also makes me think of how extreme behavior often seems to happen in plain sight. How did Sally Horner's abductor and abuser walk around freely for so long? How was Sylvia Likens abused, for months, by a whole family and two neighbors, before her murder?

"These things happen over and over again," said Weinman, "Because on the one hand we want to stare things in the face and to grapple with them. But on the other hand, it’s all too easy to look away and go, 'Well, I don’t want to intrude,' or 'I don’t want to judge.'"

It's easy to see why a keen observer of human nature like Nabokov would have been drawn to such a heartbreaking story as Horner's. Yet he was exploring similar characters and plots even before the Horner abduction. It's a subject Weinman says that "he was wrestling with for most of his adult life."

"I think it’s really important to trace it all the way through, because to the best of my knowledge nobody had really sat down and put everything together into this one big timeline sequence," said Weinman.

Even without Horner, she says, "He would have written 'Lolita' anyway. I have absolutely no doubt. However, the fact is that he certainly learned of Sally’s death at a really pivotal point when he was writing 'Lolita.' It’s pretty fair to say there was a good circumstantial case that he knew of Sally’s rescue, because the media coverage of it was quite extensive and he was somebody who was interested in crime. That’s why Sally’s story is so key to bring out and place alongside 'Lolita.' It’s not that I want Sally’s story to supersede 'Lolita.' I’ve had some people who would say, 'Oh, I’ll never read 'Lolita' now that I know that.' I don’t really agree with that idea, although I can understand why people feel that way. But I want her to be in conversation with the novel, and I want that to be a permanent conversation."

Shares