Perhaps the foremost horror of living in the neoliberal political epoch is capitulating to the myriad ways that it has devolved discourse. Now, all realms of life — social, cultural, and environmental — have been infused with the soulless rhetoric of economic efficiency. We are accustomed to hearing our peers discuss their personal brand, as though we were corporations, or one’s follower count, as though it implies hierarchy and economic power (and it does). Neoliberal culture perpetuates the right-wing myth that one’s ability to “hustle” and one’s ability to survive are correlated; the same goes for the canard that the wealthy earned or deserve their wealth, and those who do not chase wealth are unworthy, or deserve their penury.

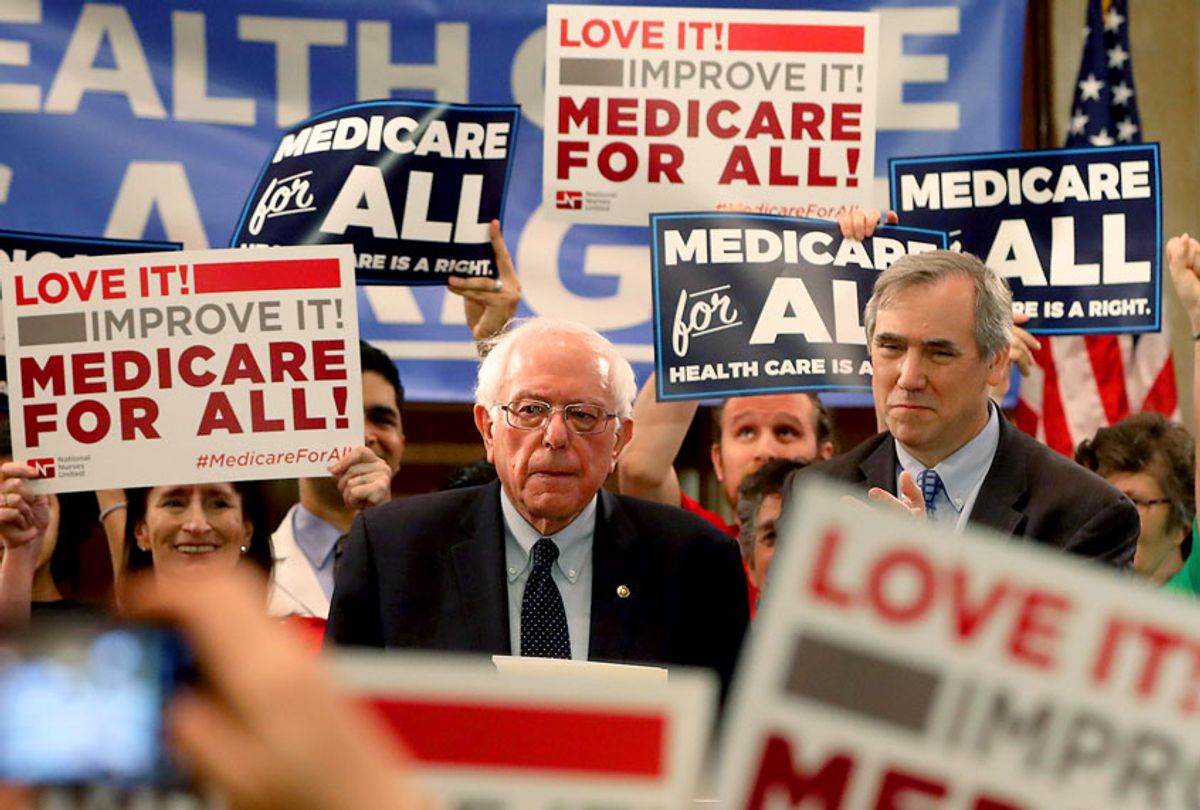

In the American debate over the right to universal healthcare, we see this rhetorical devolution reach its true potential. Every Democratic presidential candidate has an opinion about healthcare and how it is doled out; but all of them, save Bernie Sanders, are steadfast in their belief that health care should remain a market commodity, as if it were a tradable economic good on par with chocolate bars or Tickle-Me-Elmos.

A new report from the non-partisan Government Accountability Office (GAO), a federal watchdog agency, serves as a fresh damnation of the notion that healthcare should be a commodity rather than a right. The report, which Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt., commissioned in 2016, extrapolates on a rather simple question: how does income correlate with life expectancy?

The answer, sadly, is linearly. Of the richest 20 percent of Americans aged 51 to 62 surveyed in 1992, 74 percent of them were alive and enjoying old age in 2014. Going down the income quintiles, that number drops steadily: 69 percent of the same age group in the 60-80 percentile of income were still living; 63 percent of the 40-60th percentile of income; and 58 percent of the 20-40th percentile of income. Of the poorest 20 percent of Americans aged 51 to 62 living in 1992, only 52 percent of them were still alive in 2014.

This subverts the old political axiom that seniors are generally more conservative, and young persons more liberal. It may be rather that the left-leaning underclass (as income and conservatism are supposedly correlated) merely dies out faster.

As the report summary states:

Income and wealth inequality in the United States have increased over the last several decades. At the same time, life expectancy has been rising, although not uniformly across the U.S. population. Taken together, these trends may have significant effects on Americans' financial security in retirement.

The report also notes that, while “income inequality in the United States was relatively stable from the 1940s to the 1970s,” the situation changes after the 1970s, when “wage growth at the top of the income distribution outpace[s] the rest of the distribution, and inequality [rises].” “Wealth has become increasingly concentrated as well” the GAO report continues: “By 2013, those families in the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution held 76 percent of the wealth held by all families in the United States.”

And this vast wealth can purchase more material comforts, and enable access to quality medical treatment off-limits for us peasants. Thus, as medical expenses always increase with age, in our market-based healthcare system the old and rich are far more likely to have retirement savings of the kind that can pay for advanced treatment. The GAO study found that of the poorest 20 percent of households headed by someone aged 55 or older, 89 percent had no money in retirement savings accounts whatsoever. Among the richest 20 percent, 86 percent had retirement savings in 401ks or IRAs.

The study also noted that home ownership rates for the poorest quintile had dropped 9 percent between 2007 and 2016. Housing stability is a great predictor of health overall, studies have found.

There is no inequality more fundamental than the right to survive and to live one’s life unimpeded and to its full potential. Democracy and its concomitant liberties are irrelevant if its subjects are not alive to enjoy them. Thus, any so-called democracy that systematically kills off those with fewer means is a failure — structurally skewed to favor the rich and powerful, who are less likely to die young and have more means as a result.

As political theorist Michael Walzer opined, “the point of Democrat constitutionalism is to set limits on what people can do with the pursuit of power." To that end, Walzer contends that our system behooves us to “set limits on what people can do in the pursuit of wealth" — which, as he notes, we do already to some extent by outlawing theft or extortion. Why not square the circle and make healthcare universal, something that cannot be bought or sold? "There are forms of market behaviors which don’t come under the definition of theft or extortion but which are brutal in their effect on other people,” Walzer says, suggesting that we set limits on “what one can buy in the way that we set limits on what power can do in the world... people should not be able to buy Ivy League–university placements for their children, [and] they should not be able to buy expensive medical care that is unavailable to anyone else.”

Only one Democratic candidate, Bernie Sanders, favors a universal healthcare system of the kind that would largely eliminate the privatized actors that we have currently — and thus de-commodify health care. That would "set a limit," as Walzer suggested, on the ability of the wealthy to buy superior treatment.

Of all the factors affecting life expectancy — happiness, retirement resources, or stability or housing, even — enacting universal, free health care is the quickest route to curing this systemic ill, and partially restoring the promise of our democracy. (After all, democratic liberties are inaccessible to the dead.) Meanwhile, the (mostly) market-based healthcare system in America, which treats your survival and access to medicine as a commodity rather than a right, spends $30 billion a year on pharmaceutical marketing — one of many vast inefficiencies that epitomizes how health care resources would be redistributed towards actually saving lives in a universal health care system.

Shares