One week ago today, George Floyd was killed in Minneapolis by a police officer named Derek Chauvin in front of numerous bystanders. This black man's execution was so brutal and the white policeman who did it was so arrogant, knowing he was being filmed as he did it, that seemed to symbolize the entire history of racial violence in America.

For six days and nights, the people of Minneapolis have been protesting in the streets, and cities all over the country soon followed. This past weekend saw the nation erupt in anger and despair.

It's not hard to see why. There have been so many of these murders, going back centuries. And this time it happened at a moment of multiple intersecting crises — a deadly public health threat, a catastrophic economic breakdown, and long-simmering social and political volatility. After three and a half years of chaos and instability at the hands of the worst president in history, something had to give.

George Floyd's murder would be an atrocity worthy of mass protest at any time. But with all this fear, anguish and pent-up frustration on several fronts, the country just erupted.

I hope the crime that precipitated this event doesn't get lost in all the turmoil and drama of what's happening in the streets. It's important not only to keep in mind the humanity of George Floyd but also to prepare for the fact that there is every likelihood that justice is not going to be done in this case. When it comes to police killings, it hardly ever is.

Think about the New York police officer named Daniel Pantaleo who was videotaped killing Eric Garner in a similar fashion to George Floyd. Or Darren Wilson, the officer who shot the unarmed 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. Or the officers who killed 12-year-old Tamir Rice who was playing with a toy gun on a playground in Cleveland. Or the police who killed Freddie Gray, Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Samuel Dubose, John Crawford or ... on and on and on. Nobody was ever seriously held accountable for those deaths and hundreds of others.

Derek Chauvin has been charged with third-degree murder and manslaughter. We don't know if the three other officers with him that day will also be charged, or with what. It's hard to imagine they won't be. But we can already see that the system in Minneapolis is setting the table for Chauvin to escape responsibility for what he did. As usual, authorities will find a way to blame the victim for his own murder.

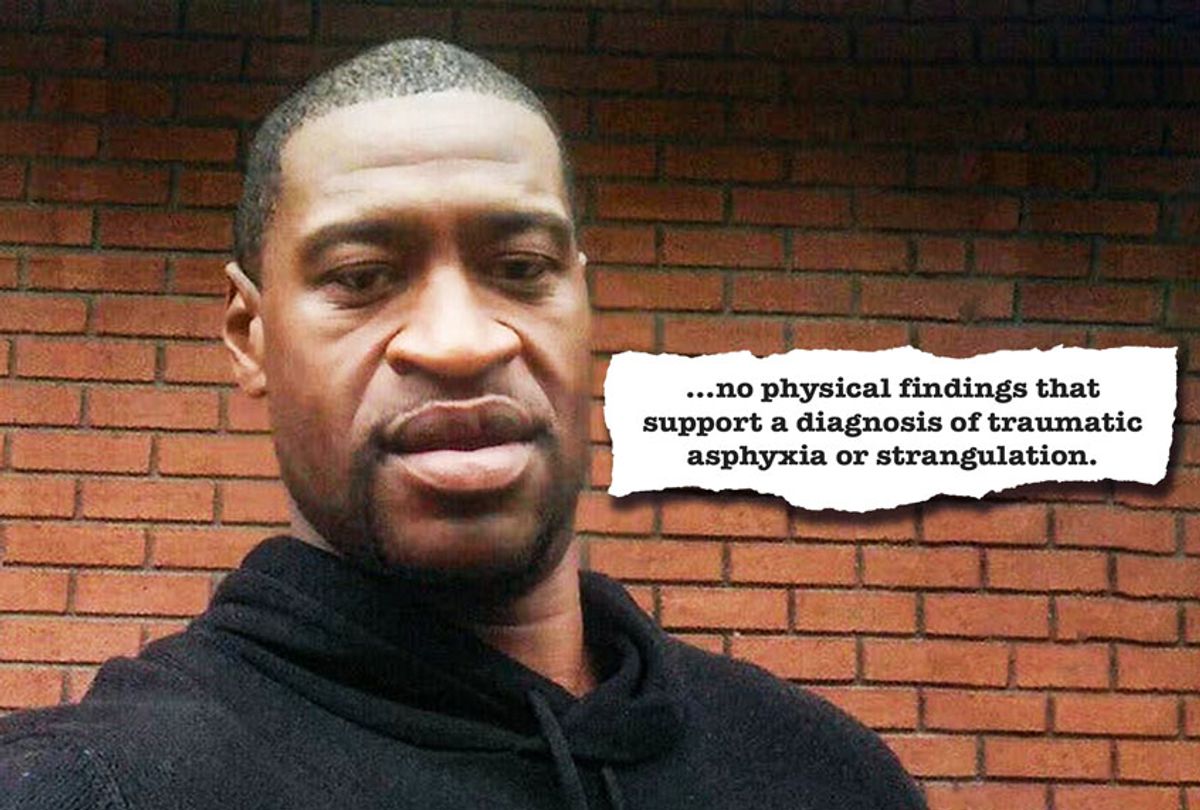

The preliminary autopsy report on Floyd's death offers the first clue. It said there were "no physical findings that support a diagnosis of traumatic asphyxia or strangulation" and hypothesized that the "combined effect of Floyd being restrained by the police, his underlying health conditions, and any potential intoxicants in his system likely contributed to his death." Floyd was 46 years old and according to the report he had underlying health conditions, including coronary artery disease and hypertensive heart disease.

I suspect they are now waiting for the test results showing whether there were any drugs in Floyd's system before they decide whether to find that Floyd died of the strange disease that seems only to afflict people who are restrained and in police custody: "excited delirium." Obviously, I don't know that, but the way that preliminary report reads, it's a fair guess.

You may be unfamiliar with this condition because it isn't a currently recognized medical or psychiatric diagnosis, according to either the "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders" (DSM-IVTR) of the American Psychiatric Association or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) of the World Health Organization. Nonetheless, it is often cited by medical examiners as the cause of death in cases like Floyd's. (There's good reason to believe that there has been a concerted lobbying effort to make that happen.)

This condition is described by the National Institute of Health this way:

Excited (or agitated) delirium is characterized by agitation, aggression, acute distress and sudden death, often in the pre-hospital care setting. It is typically associated with the use of drugs that alter dopamine processing, hyperthermia, and, most notably, sometimes with death of the affected person in the custody of law enforcement. Subjects typically die from cardiopulmonary arrest, although the cause is debated.

Diagnoses of this kind usually point to underlying conditions (such as heart disease) as contributing factors and often suggest that people in the throes of this alleged condition possess "superhuman" strength. This, of course, is meant to justify the excessive force that police insist is required to restrain them.

You may have noticed that George Floyd was a tall, muscular man who his friends described as a "gentle giant." It stands to reason that authorities will insist that Floyd was in that state, and that his heart conditions and the adrenaline rush (or any drugs that may have been in his system) pretty much caused his death. It definitely wasn't the nine minutes that Derek Chauvin ground his knee into his neck. It was his own state of agitation.

According to the Minneapolis Star Tribune, this possibility even came up at the scene:

As two officers held Floyd's back and legs, Chauvin had his knee on Floyd's neck, the charges continued.

Floyd then began repeating "I can't breathe" along with "Mama" and "please," the charges read. One or more of the officers said to Floyd, "You are talking fine" as he continued moving back and forth.

None of the three officers moved from their positions, according to the complaint. Lane asked whether they should roll Floyd on his side.

"No, staying put where we got him," Chauvin allegedly replied.

"I am worried about excited delirium or whatever," Lane said.

"That's why we have him on his stomach," Chauvin said.

The three officers continued to hold Floyd down.

Keeping in mind that "excited delirium" is a highly controversial condition to begin with, there are certain protocols police are supposed to follow. One of them is that suspects who are supposedly in its throes should not be held on their stomachs because that makes it harder for them to breathe. Placing a hold around the neck, or kneeling on the subject, is likewise considered dangerous. It appears to me that Chauvin's defense will be that he misunderstood the protocols for excited delirium.

I hope I'm wrong about that, or at least that a jury won't buy it. But unfortunately, they usually do. If they do in this case, I truly fear what will happen.

As I observed the unrest in cities all over the country yesterday, I was reminded that the Rodney King uprising of 1992 didn't happen when we all saw the video of police beating King on TV. It happened after a jury found the police not guilty.

Shares