Does Earth's solar system host eight planets — or nine?

The answer depends on who you ask. Ever since Pluto got demoted as a planet, a group of scientists still believe there is a ninth planet out there, somewhere. The evidence for it abounds in our solar system: the weird orbits of a bunch of distant objects near Pluto hint that something massive is perturbing them.

The challenge is that nobody has been able to directly observe Planet Nine. That's not entirely surprising: given its likely distance from our sun, it would be incredibly dim.

But as with dark matter and dark energy, one's inability to observe something doesn't mean it doesn't exist.

Now, a new study re-examines old observations, and calculates new ones, suggesting that Planet Nine has a higher likelihood of being a real planet in an icy, faraway part of our solar system —but closer than previously thought.

The study, published in the preprint arXiv last month and recently accepted for publication by the Astronomical Journal, suggests there is only a 0.4 percent chance that Planet Nine is a statistical fluke. This new calculation is based on both more recent observations and old evidence that made the case for Planet Nine in the first place.

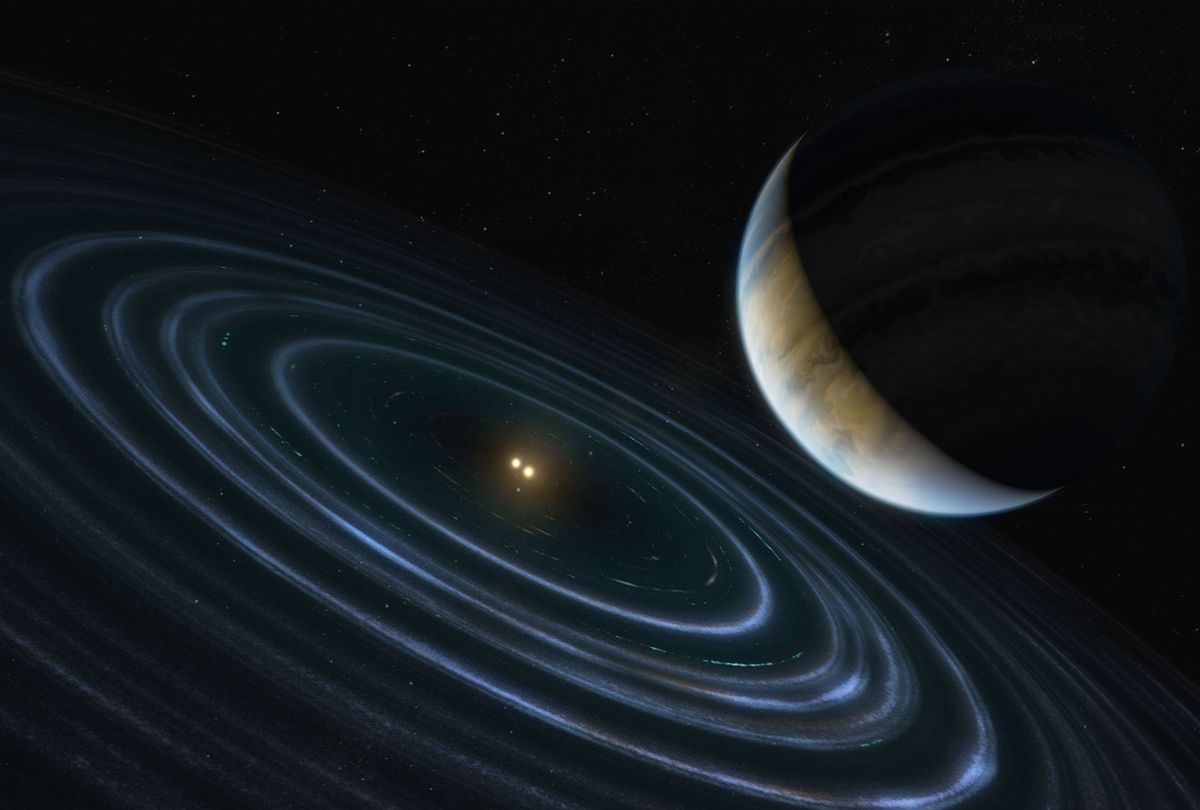

In addition to this calculation, the new study provides astronomers with a map of its orbit, and some of the best places in the sky to look for it. Its orbit was inferred by looking at the way that other objects in the outer solar system have their own orbits seemingly perturbed by some other massive object. The new proposed orbit suggests the hypothetical planet is closer to the sun than previously believed, which could make it easier for astronomers to spot. The predicted mass was also revised: based on new observations, Planet Nine is projected to be only six times the mass of Earth, instead of 20 times the size.

"By virtue of being closer, even if it's a little less massive, it's a good bit brighter than we originally anticipated," co-author of the study Michael Brown, a professor of planetary astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, told NBC News. "So I'm excited that this is going to help us find it much more quickly."

According to National Geographic, Brown estimates Planet Nine is "within a year or two from being found."

However, Brown admitted: "I've made that statement every year for the past five years. I am super-optimistic."

Meanwhile, in a blog post, Brown further explained that several factors have changed since he and his colleagues first proposed the idea of Planet Nine. First, Brown argues there's a better understanding of how Planet Nine could affect objects around it. Second, he says scientists have a better understanding of the observations that have been made over the last few years. Third, thanks to various numerical simulations, Brown and his team "understand how changes to parameters of Planet Nine change the outer solar system." And finally, thanks to a new mathematical model, scientists "now have probability distributions of all of the Planet Nine parameters."

The new paper is sure to stir a bit of a controversy in astronomy circles. Previously, speculation as to what was messing with the orbits of distant trans-Neptunian bodies fixated on the existence of a massive object — although such an object does not necessarily have to be a planet.

In 2019, a separate paper proposed a very different theory behind Planet Nine. Then, astronomers asked: what if Planet 9 were not a planet at all, but rather a primordial black hole — as in, a hypothetical type of small black hole that formed soon after the Big Bang, in the early Universe, as a result of density fluctuations? Such a novel idea might have explained why powerful telescopes have never detected so much as a flicker from the theoretical distant planet. Likewise, black holes do not emit visible light at all; rather, they absorb all photons that pass their event horizon, while occasionally emitting energy in the form of (theorized but never directly observed) Hawking Radiation.

However, Brown is hopeful that the Vera Rubin Observatory, which currently under construction atop a Chilean mountaintop, will be able to discover Planet Nine when it is available to astronomers in 2023.

For the unfamiliar, astronomers believe that Planet Nine exists in part because a handful of objects in the Kuiper Belt appear to be clustered in the same orientation in space. This could be random, but the pattern observed to these objects' orbits makes it more likely to be the result of the gravitational force of an elusive, massive object — hence, Planet Nine.

However, critics have often said "observation bias" could be the truth behind Planet Nine. In Brown's blog post, he admits "bias is real," but also notes, "I am here to show you that it doesn't cause the clustering that we see."

As Brown explains: "There is a lot of bias, and the observations generally fal [sic] along the lines of bias. But the bias clearly cannot account for the fact that the orbits are tilted and that they are tilted in one direction."

If discovered, it will be the first planet in our solar system to be found since Neptune in 1846. Similar to Planet Nine, astronomers discovered Neptune using mathematics after noticing Uranus was being pulled slightly out of orbit by an unknown body. Astronomers were able to infer how much mass the unknown planet had, and then where to look.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Shares