Who would've thought that a street form of music – that many said wouldn't last, created by a collection of disenfranchised Black and brown kids from the Bronx – would grow into a billion-dollar industry, while producing generational wealth for the written-off, inspire every cultural inch of the globe in some way and would surpass rock as the most popular genre in the United States? Well, we thought it – and you would have thought it too if you were there.

Hip-hop is older than me, so I was born into a culture still in its infancy. And I'm from Baltimore, not the Bronx, meaning I don't necessarily have a connection to the genre's place of origin. Still, I do, as the two cities are connected by poverty and pain. We speak the same other-America language, you know – the schools are broken, cops and politicians participate in lying contests, and making it to 25, sometimes 21, is a pipedream because if the cops don't get you and stick up, kids don't get you, then the system would.

Some murders occurred in my east Baltimore neighborhood – three that I remember clearly before I turned 8. And I was too young to drown in my own tears or chime in when the older kids screamed revenge, so I just listened, often with a feeling of urgency. Everything had started becoming more urgent around that time – I needed a goal, a plan and some experience because life could end as soon as today. One of the murdered three was a year younger than me.

One of the murdered three was a year younger than me.

Music had become one of the strongest coping mechanisms for some of the other kids in the neighborhood. They always talked about the ways Public Enemy, Kool G Rap, Rakim, and KRS 1 spoke to our experience. Big Teddy from across the street was in awe with the KRS 1's "Love Gonna Get'cha (Material Love)."

It wasn't strange to see Big Ted, who was only three years older than me, poke his head out of weed smoke, just to chant:

Money's flowin', everythin' is fine

Got myself an Uzi and my brother a nine

Business is boomin' everything is cool

I pull about a G a week; f**k school!

A year goes by and I begin to grow

Not in height but juice and cash flow

While Big Teddy put on this mini performance, he would flash his pistol on the part where KRS1 said "nine" and then wave a wad of cash or parts where "G" and "cash flow" were mentioned. The tragedy was that the song did not glorify guns and drug dealing – it was the rapper's conscious attempt at explaining the consequences of a life of crime. Material love displayed the ugly side capitalism and chasing luxury items over love, family, and knowledge, but no one taught us that.

Dude kept like 50 cassette tapes in his backpack, carrying everything from A Tribe Called Quest and Leaders Of The New School to west coast acts like MC Eiht and Too Short.

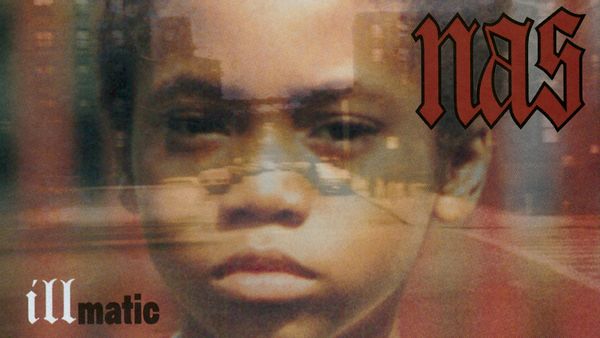

I really enjoyed the music as a small kid, but wasn't honestly transformed by hip-hop until I heard a mix tape, from the unreleased Nas album "Illmatic" back in 1993. Now, the album didn't come out until 1994, but hip-hop artists used to release tracks on mix tapes in the effort to see how the streets was going to engage with the upcoming albums. This let them know what kinds of songs were going to make the final cut and more importantly, what singles to drop.

"Illmatic" by Nas (Sony)

"Illmatic" by Nas (Sony)

I was tying my Nikes extra tight on the basketball court, when Duncan planted has boom box at the end of the bench. Duncan wasn't much of a ballplayer, but definitely leaped at any chance to provide the soundtrack. Dude kept like 50 cassette tapes in his backpack, carrying everything from A Tribe Called Quest and Leaders Of The New School to west coast acts like MC Eiht and Too Short. But on this day, Duncan didn't really speak, he didn't tell us what he was about to play, he didn't do anything, except pop in a tape, cranked up the volume and put his head down in a nod as a raspy voice projected out of the speakers telling the biggest lie in hip-hop history, "I don't know how to start this s**t, yo – now."

Nas knew exactly how to start it.

Rappers; I monkey flip 'em with the funky rhythm

I be kickin', musician inflictin' composition

Of pain, I'm like Scarface sniffin' cocaine

Holdin' an M16, see, with the pen I'm extreme

Now, bullet holes left in my peepholes

I'm suited up with street clothes, hand me a 9 and I'll defeat foes

Y'all know my steelo, with or without the airplay

I keep some E&J, sittin' bent up in the stairway

Or either on the corner bettin' Grants with the cee-lo champs

Laughin' at base-heads, tryna sell some broken amps

Everybody ran over toward the boom box, demanding a rewind. Some kids yelled, "Who is that?!"

"Nas," Duncan said as he rewound tape, "Nas."

The cocktail of his voice and the simple but gritty beats screamed at me. The artist along with his entire existence were foreign to me, but instantly seemed so relatable.

The image of a base head (what some called crack addicts back in the early '90s) trying to sell some broken speakers, felt like my neighborhood, it felt like home. We hid our video games, speakers and radios from our addicted family members because we knew they could be snatched away in an instant. It wasn't a vanilla depiction of a street experience, it was a portrait, a snapshot of what was happening directly across the street from the basketball court, all through our blocks and buildings and in our homes.

G-packs get off quick, forever n****s talk s**t

Reminiscin' about the last time the task force flipped

N****s be runnin' through the block shootin'

Time to start the revolution, catch a body, head for Houston

Once they caught us off-guard, the MAC-10 was in the grass, and

I ran like a cheetah, with thoughts of an assassin

Picked the MAC up, told brothers "Back up!" — the MAC spit

Lead was hittin' n****s, one ran, I made him back-flip

Heard a few chicks scream, my arm shook, couldn't look

Gave another squeeze, heard it click, "Yo, my s**t is stuck!"

Tried to cock it, it wouldn't shoot, now I'm in danger

Finally pulled it back and saw three bullets caught up in the chamber

The song has two long tangled verses, but separating them down into poetic stanzas gives me the opportunity to pluck the images that were defining a poor Black early '90s experience. The quote above references heading to Houston after getting in trouble, which has been a uniquely Northern experience. So many Black people from New York all the way down to DC have roots in the Deep South, including the Carolinas, more southern parts of Virginia and Texas. Sending your kids south was the cure for arrest warrants, teen pregnancy, a poor performance in school, being bullied or anything your parents couldn't handle at that particular time. The Fresh Prince was from Philly, and they sent dude all the way to Bel-Air because of a fist fight.

And there's the task force flipping, something extremely common during the crack era when the album was created. Plain clothes cops who we called Knockos or Knockers, used to pull up on our fronts when their arrest stats were low, and chase us and cuff us and pound on us and plant what they could on who ever they caught.

We complained about this for years in Baltimore, and no one listened until these actions lead to the death of Baltimore City Homicide Detective Sean Suiter.

So, now I'm jettin' to the buildin' lobby

And it was full of children, prob'ly couldn't see as high as I be

(So, what you sayin'?) It's like the game ain't the same

Got younger n****s pullin' the triggers, bringin' fame to their name

And claim some corners, crews without guns are goners

In broad daylight, stick-up kids, they run up on us

.45's and gauges, MAC's in fact

Same n****s will catch you back-to-back, snatchin' your cracks

In black, there was a snitch on the block gettin' n****s knocked

So hold your stash 'til the coke price drop

The high-level poetry continues throughout the song when Nas gives of image of running through his building, high trying to escape, wondering if children are scattered, probably not trying to hit them, or include them in the ensuing violence. But how do you protect the children when that are in the same fire as you?

I know this crackhead who said she gotta smoke nice rock

And if it's good, she'll bring you customers and measuring pots

But yo, you gotta slide on a vacation

Inside information keeps large n****s erasin' and their wives basin'

It drops deep as it does in my breath

I never sleep, 'cause sleep is the cousin of death

Beyond the walls of intelligence, life is defined

I think of crime when I'm in a New York State of Mind

People suffering from addiction where a vital part of society. Obviously the users were customers, but they also brought supplies to the dealers in exchange for product when their money was short. Some of those same users and dealers also gave information to the police that left kingpins in prison and their wives using as a result to dealing with the pressure of having an incarcerated spouse.

The underworld felt like the only way to achieve social mobility for many of us.

Be havin' dreams that I'm a gangsta, drinkin' Moëts, holdin' TEC's

Makin' sure the cash came correct, then I stepped

Investments in stocks, sewin' up the blocks to sell rocks

Winnin' gunfights with mega-cops

But just a n**** walkin' with his finger on the trigger

Make enough figures until my pockets get bigger

I ain't the type of brother made for you to start testin'

Give me a Smith & Wesson, I'll have n****s undressin'

Thinkin' of cash flow, Buddha and shelter

Whenever frustrated, I'ma hijack Delta

In the PJ's, my blend tape plays, bullets are strays

Young women is grazed, each block is like a maze

Full of black rats trapped, plus the Island is packed

From what I hear in all the stories when my peoples come back

Dreaming of being a gangster is something constantly handed down to us. Professions like doctors and lawyers never quite seem within reach. After all, lawyers were in the courts, and we only saw them through the lens of criminal justice, and who in the hell knew a real medical doctor? So, the Scarface reference was on brand and touched so many people in urban America, especially since it told the tale of an immigrant who came from the bottom and fought his way to the top via the underworld, as the underworld felt like the only way to achieve social mobility for many of us.

Nas also references a gun problem that is so bad that even innocent women are grazed in his housing project complex Queens Bridge, which was really like a maze full of rats. New York just hired a rat czar. "The Island is Pack" refers to Rikers – at the beginning of what we eventually call the prison industrial complex. Young black men from the neighborhood were shipped in as if on a conveyor belt, coming out unemployable in many situations, destined to return.

Black, I'm livin' where the nights is jet-black

The fiends fight to get crack, I just max, I dream I can sit back

And lamp like Capone, with drug scripts sewn

Or the legal luxury life, rings flooded with stones, homes

I got so many rhymes, I don't think I'm too sane

Life is parallel to Hell, but I must maintain

And be prosperous, though we live dangerous

Cops could just arrest me, blamin' us; we're held like hostages

It's only right that I was born to use mics

And the stuff that I write is even tougher than dice

I'm takin' rappers to a new plateau, through rap slow

My rhymin' is a vitamin held without a capsule

The smooth criminal on beat breaks

Never put me in your box if your s**t eats tapes

The city never sleeps, full of villains and creeps

That's where I learned to do my hustle, had to scuffle with freaks

I'm a addict for sneakers, 20's of Buddha and girls with beepers

In the streets I can greet ya, about blunts I teach ya

Inhale deep like the words of my breath

I never sleep, 'cause sleep is the cousin of death

I lay puzzled as I backtrack to earlier times

Nothing's equivalent to the New York state of mind

I played the song over and over again – until I captured every reference, every rhyme and every image and then played it more.

I even played it for Big Teddy and a collection of other brothers serving time in a youth jail for petty drug crimes. They lined up by the phone for individual listens or pressed their ears to the receiver as a collective, saying, "Run it back!" as soon as the song ended, and I did.

The album, especially that song "N.Y. State of Mind," became a part of me. About 20 years after its initial release, when I officially attempted to begin my own writing career, Nas and "Illmatic" remained my most significant influence. Toni Morrison and James Baldwin were the best, but hip-hop and Nas made me feel like I could do it too.

Happy 50th birthday to hip-hop. Without it, many of us, wouldn't be here.

Read more

about this topic

Shares