In the candid, absorbing documentary, “Pee-wee as Himself,” the late Paul Reubens wants to set the record straight. While he kept a very private life — hiding his homosexuality as well as his cancer diagnosis from the public — he received much unwanted attention following an arrest for indecent exposure and additional legal trouble for a child pornography case that resulted in a misdemeanor obscenity charge.

Even as Reubens wanted to impact kids with TV the way it impacted him, he lost part of himself by having his alter ego pass as a real person.

Director Matt Wolf shrewdly recounts Reubens’ life and his career as both Pee-wee and the "character" of himself in this revealing two-part documentary, in which Reubens talks about his childhood and his experiences at Cal Arts, as well as a same-sex relationship that ended so Reubens could have a career. Developing his comedy stylings at the Groundlings, Reubens is shown making a beeline towards fame, achieving it when “The Pee-wee Herman Show” became a hit on stage, then through a TV series and movies. The clips Wolf assembles from a phenomenal archive are thrilling to see. So too are the interview segments from the 40 hours Wolf recorded with Reubens.

Even as Reubens wanted to impact kids with TV the way it impacted him — he was a big fan of “Howdy Doody” and other children’s shows — he lost part of himself by having his alter ego pass as a real person. His efforts to control his career and get recognition as Paul Reubens sometimes amounted to self-sabotage.

In “Pee-wee as Himself,” Reubens wants people to see him as he really is. He tells his story to Wolf, creating disruptions at times because he is concerned about how he comes across. As a result, the documentary is both bittersweet and illuminating.

Wolf spoke with Salon about making “Pee-wee as Himself” and collaborating with Paul Reubens.

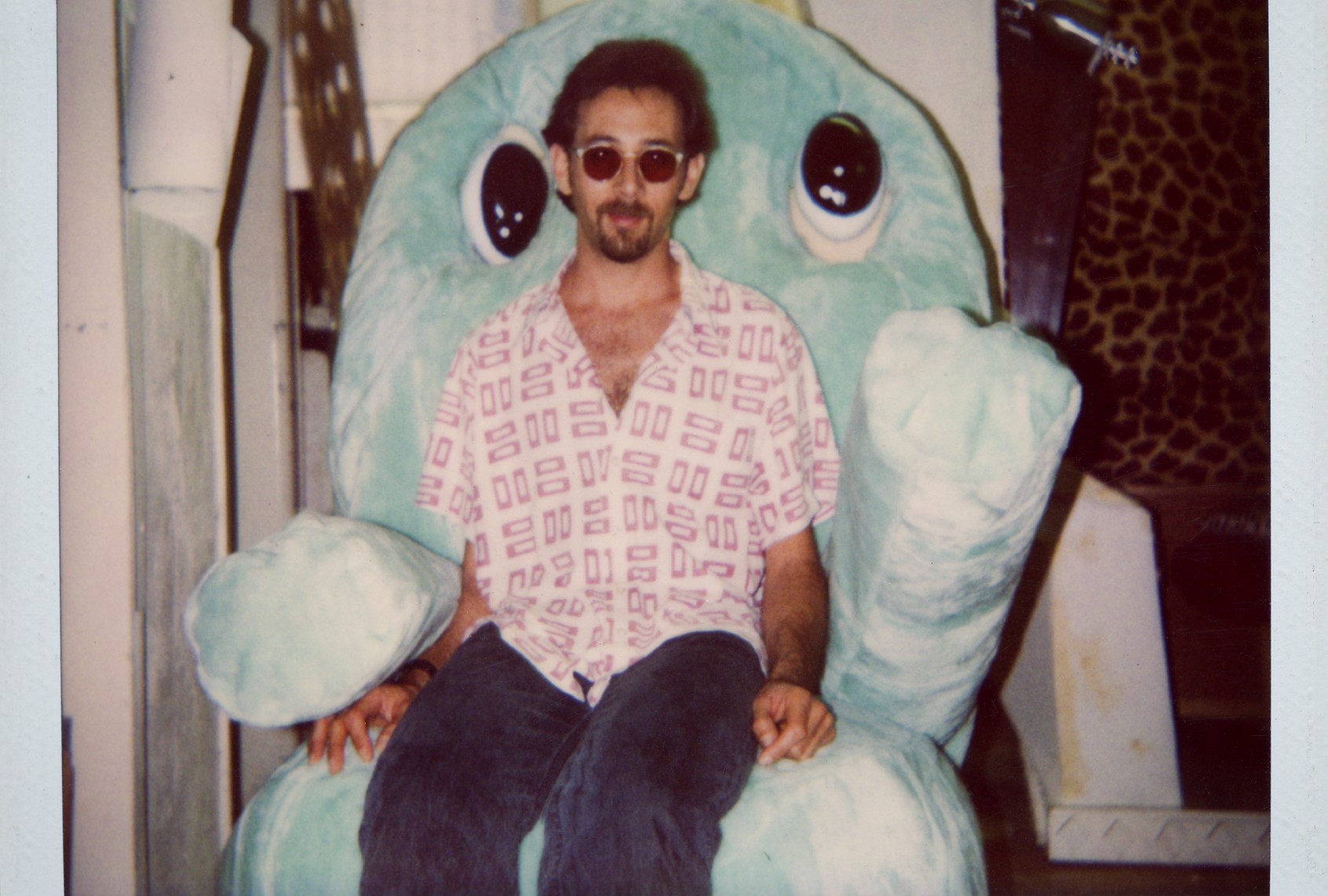

Paul Reubens sitting in Chairy (HBO/Pee-wee Herman Productions, Inc.)How did you get involved in this project and conceive of the documentary?

Paul Reubens sitting in Chairy (HBO/Pee-wee Herman Productions, Inc.)How did you get involved in this project and conceive of the documentary?

I came of age on “Pee-wee’s Playhouse.” That was a touchstone for me. “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” was my first real encounter with art that I had a visceral, emotional reaction to. That stayed with me. I had a pull-string [Pee-wee] doll hanging above my bed, and I took a photo of the doll in my high school intro to photography class — that photo is still on my refrigerator. I was a fan. When you make documentaries, people always ask who your ideal subject would be, and I would say Paul Reubens. But I didn’t know much about him. I understood he had gone to Cal Arts in the conceptual art heyday of that school and that he was part of the Groundlings, an experimental theater group, but other than that, I didn’t know much.

There was a rumor in the trades that the Safdie Brothers were working with Paul on his long-rumored dark, autobiographical Pee-wee film. I approached them to ask if it was true and expressed my interest. It wasn’t true, but fortuitously, Paul had been wanting to make a documentary, and he approached Emma Koskoff, who would become my producer. Our first meeting was during the height of the COVID-19 lockdown. What he said was what he says in the beginning of the film: “I want to direct a documentary of myself, but people are advising me against it, and I don’t understand why.” I said I wanted to talk about having me direct a film, and why don’t we get to know each other and maybe conceive of a process to move through that. We had dozens of hours of conversations until Paul sort of begrudgingly agreed to proceed on the condition that I was on a trial period. [Laughs]

During that trial period, I insisted we speak three times a week, so we were having six hours of conversations a week for a month. They were expansive, from hanging out and shooting the sh*t to really getting into the nitty gritty of his story and how I might tell it. I found these conversations to be thrilling and tricky. It was an obstacle course to choose my words wisely and put Paul at ease about my intentions. I wanted to do an affectionate portrait of him, but one with complexity and nuance. I wanted to dissect and interrogate the origin story of Pee-wee and the cultural backdrop in which this impish character emerged, while also contending with the personal choices Paul had made to separate himself from this alter ego.

"We had dozens of hours of conversations until Paul sort of begrudgingly agreed to proceed on the condition that I was on a trial period."

There was obviously sensitivity around Paul’s arrest; he didn’t want that to be sensationalized. That wasn’t my interest, but he also knew we had to address it. But more significantly, Paul made the decision prior to doing the documentary that he wanted to come out. As you know, I am a gay filmmaker and have made films about other gay artists. That was a point of connection and tension between Paul and me. He wanted to come out, but he was ambivalent and anxious about it. I think he was concerned I would focus too much on that aspect of his story or try to frame him as some sort of gay icon when that wasn’t how he saw himself. I would insist to Paul that the film was going to be in his own words, so I would help him figure out how to describe and discuss his sexuality on his own terms, which he did.

It was a long, long process of building a relationship that was a two-way street. I wasn’t just an observer. I was engaged in a complex relationship with Paul, and early on we decided that our dynamic could be an interesting dimension of the film. We recorded our private conversations. I moved to Los Angeles for a few months and filmed all the interviews that appear in the film, but Paul wasn’t sitting down to do his own interviews, and I was concerned that might never happen. Then one day he said, “I am ready, let’s just get on with it.” That would become an epic 10-day interview over the course of two different filming periods.

Tim Burton and Pee-wee filming "Pee-wee's Big Adventure" at the Alamo (HBO/Pee-wee Herman Productions, Inc.)Did you, as Reubens suggests in the film, have an agenda here?

Tim Burton and Pee-wee filming "Pee-wee's Big Adventure" at the Alamo (HBO/Pee-wee Herman Productions, Inc.)Did you, as Reubens suggests in the film, have an agenda here?

"I think he was concerned I would focus too much on that aspect of his story or try to frame him as some sort of gay icon when that wasn’t how he saw himself."

I don’t really have an agenda when I make a film. It’s more about finding myself in the material and figuring out what I gravitate to emotionally, or what is intriguing to me. And this is the film I made where it was most obvious what my connection to it was. It was visceral. It was personal. We had stuff in common. I saw myself in Paul in many ways, and in other ways, we were entirely different — because of generational differences and because he was a celebrity who endured scrutiny and controversy. He carried around a certain amount of trauma, and I was sensitive to that. I wanted to make a portrait of an artist like other portraits I have done of visionaries who beg for reappraisal. That is my wheelhouse, and Paul fit right in, except he was an icon. The power dynamic was different because of Paul’s celebrity. But I was very, very intent on not making a conventional celebrity biopic and having a march of talking heads, many of them high profile, singing platitudes about the central subject, and having that person perform an exercise in introspection that is fairly superficial and controlled. I was always encouraging Paul to “not be simple.” Everyone knows you are complicated. Embrace your complexity. It’s OK. And I think he did. I had to convince Paul to show his full complexity and to move away from the traps of the celebrity documentary we are seeing dominate that genre and ecosystem.

What can you say about working or collaborating with Paul, as your interactions in the film are sometimes fraught?

"I wanted to make a portrait of an artist like other portraits I have done of visionaries who beg for reappraisal."

There was a power struggle between us. There was a lot of mutual respect and affection between us and a lot of friction. I found working with Paul to be equal parts contentious and thrilling. I had final cut, and he had “meaningful consultation,” which is commonplace in documentaries these days, and it is an amorphous concept that he struggled to wrap his head around. It was confounding to him that a filmmaker could take his life as the raw material for their own work. He wanted to be collaborative, but he wanted to control every frame, and that was a source of tension we kept punting. I wanted to put Paul at ease so we could capture the material we needed to tell his story, but that friction was accelerating. All that said, there was a certain understanding between us that we shared the same goals. What I wanted was to get Paul to integrate different parts of himself that he had not integrated before. I think that was a very uncomfortable process. He felt vulnerable and out of control. He wanted to be vindicated and to have the opportunity and platform to set the facts straight as to what happened with the controversies surrounding him in the media, because it was unjust. That’s the easy part, because it is not the most interesting part of his story. The harder part was to show his full complexity, to show who he was, because he was ambivalent about sharing that with the world. He was complicated and intense and combative, and also sensitive and sweet and empathic, and wildly creative, imaginative and curious. I wanted to encompass that full scope of who he was and the big range of feelings of his story — the joy and humor and tragedy. In some ways, we had an amazing collaboration, and in some ways, we were at war with each other.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Is Reubens an unreliable narrator in his own documentary? How much do you believe of what he told you? What surprised you?

"I didn’t know he was sick [with cancer]. That is a pretty big omission."

I think we’re all unreliable narrators of our own stories because there is a limit to how much we understand about ourselves. But more significantly, there is a limit to how much anyone can understand the inner life of someone else. Everyone is entitled to their own inner life, and that isn’t always accessible. There are many versions of Paul. I experienced more versions of him than others who knew him. He was someone who held his cards close to his chest. I didn’t know he was sick [with cancer]. That is a pretty big omission. Paul was a gifted storyteller and conceptualized a way to tell his own story. I interviewed other people for contrasting perspectives and to gain insight. But at the end of the day, this was a film in Paul’s words about the inner life Paul wanted to share, and on terms he felt comfortable with. But I think he surprised himself with the level of candor and vulnerability he was willing to share on camera. The curiosity is because he is such an insanely compelling person. But there will always be limits to how much we understand someone else. I had to grapple with that in a profound way when I learned that Paul was battling cancer after spending hundreds of hours speaking to him.

As with all your films, “Wild Combination,” “Teenage” and “Recorder” among them, you are skilled at using archival material to tell your stories. How did you decide what to use and what points to make about his life and career?

I build my films around the strength of the material. I have a team of people looking through the archives with me even before I start shooting interviews. I have a sense of what is the most compelling material that I am going to structure the film around. This film had extraordinary, revelatory material, almost all of which Paul had saved in a closet in his bedroom. He was an archivist himself. Paul’s life and career were meticulously documented. It is extraordinary that there is footage from his time at Cal Arts and photographs. In the late '70s, people weren’t filming those types of performance art workshops. There is very little footage of the Groundlings. That was a scrappy little group. They didn’t know that what they were doing would be of great historical significance. Most of the footage is from Paul’s Super-8 [recordings]. It was an embarrassment of riches.

The film is about Reubens’ personality — both public and private. How did you balance between these two worlds, especially since Reubens kept much of his personal life secret?

There are three threads in the film — the story of Pee-wee, the story of Paul and the meta thread about his relationship with me and his ambivalence about being the subject. It was with my editor, Damian Rodriguez, a process of interweaving and braiding those three strands. I talk about doing a portrait by integrating different sides. That can be revelatory to the audience, but also to the subject in real time on camera. Paul made the choice to split into two different versions of himself, Paul and Pee-wee. Through the process of making the film and that tense interpersonal exchange between us, he’s grappling with integrating these two parts of himself. But in the actual filmmaking, I am mashing these things up together so that there is an ebb and flow that I hope is seamless and, in a way, I think, helps you oscillate between the mental states of this complex person.

Pee-wee’s Playhouse (HBO/Pee-wee Herman Productions, Inc.)What do you think were Reubens' hangups with separating life and work? He had self-hate and self-preservation; he craved fame and success, but he lost his anonymity. He was arrogant and self-sabotaging. Is this a cautionary tale of fame?

Pee-wee’s Playhouse (HBO/Pee-wee Herman Productions, Inc.)What do you think were Reubens' hangups with separating life and work? He had self-hate and self-preservation; he craved fame and success, but he lost his anonymity. He was arrogant and self-sabotaging. Is this a cautionary tale of fame?

"Paul would not have succeeded as an openly gay person in the context of children’s television entertainment."

It’s sort of Faustian. He makes this great sacrifice of having a personal life to make this great art and be this tremendous success, and it all backfires and comes tumbling down. That is a story that is not unusual for many celebrities, but it was uniquely devastating for Paul, who had been so vigilant about protecting his private life. I think of it not as a cautionary tale but a generational experience, particularly for gay people. Paul would not have succeeded as an openly gay person in the context of children’s television entertainment. I don’t think he went into the closet only to succeed professionally. I think he made personal decisions. He organized his life in a way that served him professionally and that worked for him personally for a long time, until it didn’t. When it didn’t, it was devastating for him because the world saw Paul through his scary mug shot. It is a very small club of people who have an alter ego that only exists in public and a totally distinct and separate private life. It’s who Paul was, and he had to reconcile some of those choices later in his life and come full circle to both accept himself and maintain his commitment to one of his earliest creations.

There are brief mentions of conflicts he had with folks he worked with. You don’t discuss his lawsuits. Can you talk about that focus? I appreciated that you kept some things private, but I feel there is more he is not telling us.

Fortunately, the archival material contained some of those contradictions and conflicts, and so did other people who knew him. I think that’s the value in contrasting perspectives and allowing the primary material to speak for itself. There were limits to how much Paul felt comfortable talking about his relationship with Phil Hartman, who died very tragically, and Paul was sensitive to not speaking ill of him. I think Phil betrayed Paul when he spoke so negatively about him on the “Howard Stern Show.” I’m sure that affected Paul. I didn’t have an opportunity to ask Paul about that, but it’s in the material. There are limitations to what people feel comfortable discussing, and there are boundaries that are healthy and realistic for people who have lived public lives — and I accept that. As documentary filmmakers, there is always more we can have, or a scene we missed, or a subject we wish our interview subject would cover, or there wasn’t enough time. I had limits in the sense that Paul passed away, but I had so much rich material in our 40 hours of conversation and 1,000 hours of archival material that I got a complete picture of who he was.

Did Paul get to see the doc before he died?

I showed Paul 45 minutes of a very early rough cut to convince him that what we were doing was in the spirit of what we always discussed. He was supportive. But that didn’t mean that the conflict between us was suddenly resolved. I am grateful he was able to see some of the film, because I think he knew that what I set out to do was what I was up to.

What did you think of his post-Pee-wee performances? I find that chapter of his life the most interesting.

He’s a gifted character actor. A lot of people who knew Paul wish he had explored more sides of his incredible talent. I respect his laser focus and decision to entirely commit to one creation. It shows a significant amount of restraint to do that. But he didn’t have a choice. He had to reinvent himself, and in that opening, he had the opportunity to create a bunch of different characters that put his talent on full display. I only wish that Paul had an opportunity to play more and more characters. I know that his commitment to Pee-wee was enduring, and he felt an ongoing connection to that alter ego. That lasted for him, and it is rare and special that interest and curiosity about a character continues across decades.

Can you ever look at “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” the same way again?

When you make a film about something that you love, it becomes part of you. I like to make films not just out of an appreciation, but to turn the material into part of my own life experience. Pee-wee is a part of my life in a real way. Paul is someone I had a relationship with — a very complex and intense relationship. It is part of me, but it always had been part of me. I don’t think I will be watching “Pee-wee’s Playhouse” anytime soon, but I know that show in such a visceral way that it will always be part of the fabric of who I am. It was in the past, and now even more so.

“Pee-wee as Himself” premieres May 23 on HBO and MAX

Read more

about Pee-wee Herman and Paul Reubens