As author Lily Burana once explained, stripping is fast money. But it's not easy money. And despite an abundant array of memoirs and movies over the past several years that have explored the experience of stripping, few have acknowledged the actual work of it. (Burana's seminal 2001 "Strip City" remains one of those bright exceptions.) Dancing is demanding physical work; it requires skill, strength and technique, as well as sophisticated interpersonal skills.

If you were living in the Bay Area in the '90s, you would have had an opportunity to witness that truth firsthand via the trajectories of two very different establishments. At the Mitchell Brothers' famed O'Farrell, a group of dancers sued — and eventually won — the right to be designated as employees rather than independent contractors required to pay stage fees to perform. And at the Lusty Lady, its famously alternative dancers organized to form one of the most unique labor unions in the nation. The Lusty Lady shut down in 2013, but a new memoir recalls its upstart heyday, and the enduring lessons of collective action.

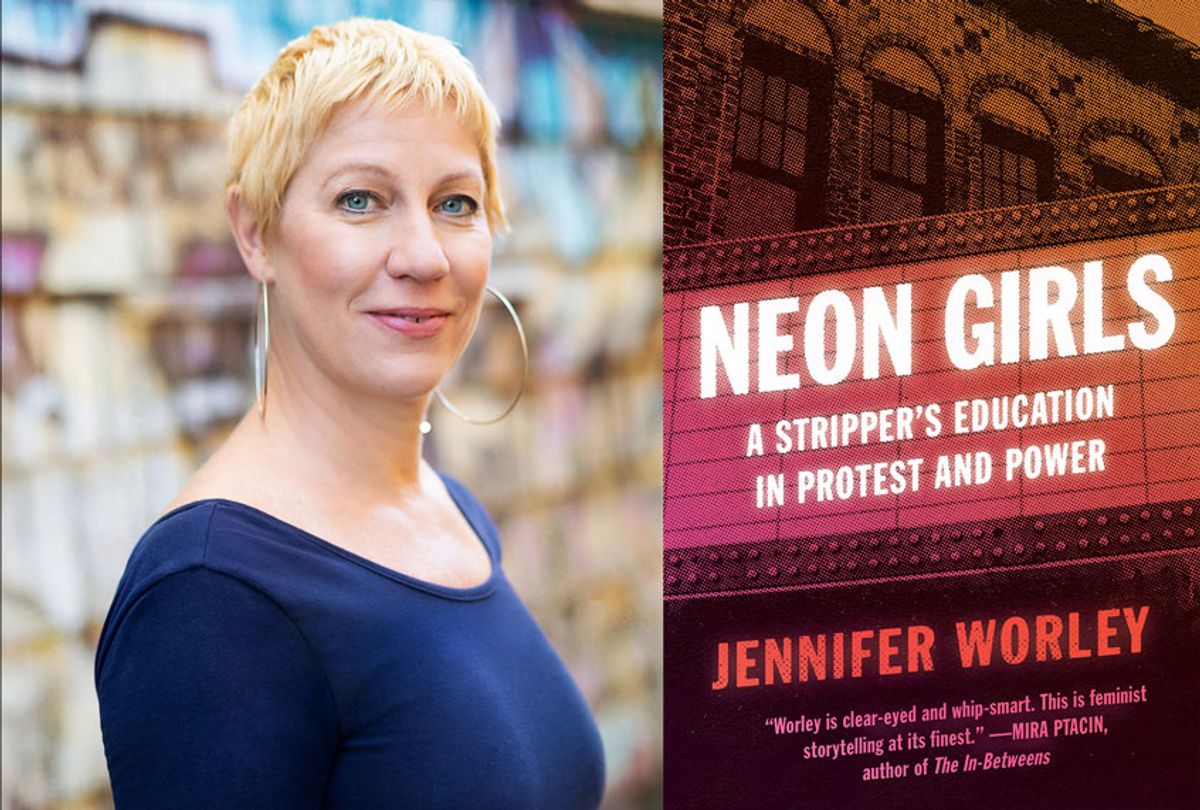

Now a professor of English at City College of San Francisco — and president of its faculty union — author and former dancer Jennifer Worley talked to Salon recently via phone about "Neon Girls: A Stripper's Education in Protest and Power."

For someone who doesn't know what the Lusty Lady was, how would you describe that place? How it was it, in so many ways, a touchstone, a metaphor, for dancing and for dancers?

The first thing to know is really just the physical architecture of the space, which was different from a strip club. It was a peep show. Rather than the dancers being up on an elevated proscenium stage with an audience sitting below them, the dancers were in an enclosed space was lined with mirrors on the ceiling and all the walls. There would be three or four dancers at a time in that enclosed room, which was what we called the stage.The customers were separated into little individual booths, and they would slide money into a coin slot or a bill acceptor. In order to get visual access, they had to continue putting in money There was glass window between us and the customers; it was just purely visual. There was no physical contact or lap dancing or any of those things. The dancers were all together on the stage at once and the customers were separated from each other. And the reason I am taking time to describe that architecture is that I think it was crucial to what it was like to work there for a young woman in the '90s and really crucial to the organizing that went on there later.

In most clubs, you have one dancer on the stage and then the men are all kind of together. You could have a whole bachelor party come in, and they're joking and buying each other lap dances. There's a real power dynamic in that, where it's the one woman and a whole bunch of men who are in a mass. At the Lusty Lady, it was the women who were together and the men who were separated out, and that it gave us a certain kind of power. They couldn't physically touch us, and we had a lot of control over them. If they were behaving in a way we didn't like, we could actually tell them. If a guy was rude to a particular dancer, we would do a little silent boycott of him. No one would dance for him. There was a real shift in the power dynamics, that came in part from the architecture of the place. We were in there together and could support each other.

There was a reputation in San Francisco that it had a more feminist perspective. Our managers were women, mostly former dancers. Some of the rules at the place were that the men were not allowed to direct us or tell us what to do. They weren't allowed to make disparaging comments about us. We had a sexual harassment policy. This was the mid-'90s. I worked in publishing before that, and the policy was, "Sexual harassment is anything that makes a woman feel uncomfortable."

That's not to say that there were problems, both in the theater itself and the sex industry as a whole. But the women who worked there were an interesting group of caustic and powerful and interesting activists, students, young moms. Just a really, really amazing crew of women.

The dichotomy between that, and then what was going on at places like Mitchell Brothers at the same time is incredibly illustrative of what a community of dancers could be.

The Mitchell Brothers was the more traditional theater with that traditional stage. The Mitchell brothers O'Farrell theater is where lap dancing was actually [pioneered] in the '80s. It was considered a really upscale, exclusive club where the women had a very Playboy aesthetic — slim, pretty, big tits, long hair, all of that. But at the same time, those women were getting really ripped off by the owners. They were forced to pay these enormous stage fees. In order to come into work, the bosses classified them as independent contractors rather than employees. That meant they didn't need to pay them even minimum wage, but more importantly, they could actually charge the dancers a fee to come into work.

By the time I was dancing, they were paying well over a hundred dollars. It was really exploitative in the sense that once the management was making money off the dancers, they didn't really have that much incentive to keep a particular ratio correct. If you were making $200 a night from every woman who comes into dance, you could just load up the stage and load up the club with tons of dancers who all have to compete with each other.

When that's the situation, then you're competing for the bottom line, the lowest common denominator. It becomes a contest of who will do more for less, and it's just really sets up the workers to be in this direct competition with one another. That's another part that really made the Lusty different, in that we weren't in direct competition for our wages. We were paid hourly; we punched a time clock. It wasn't like, "Oh, so-and-so gets these windows to open for her. That means I'm not going to make my rent today." And that really allowed us to, I think, have a lot more solidarity with each other, than with the economic structure of other clubs.

This is a book about dancers, but it's also about labor and about unions and fair wages. It seems significant that the words "protest and power" are on the cover of your book. What do you feel like that experience at the Lusty Lady taught you about what's going on right now in our country?

Obviously, there's a huge difference in the issues and the scale of the oppression that people are talking about right now. Black people now are talking about 400 years of slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, police brutality, and terrorism. I don't want to minimize that, because that is profound and it's probably the deepest issue in our country, if not globally.

That said, one of the things that really was powerful for me was the unquestioning support for each other that we had. In our case, we were pressuring our employer to come to the bargaining table in earnest. They had been stalling and trying run to down the clock at the bargaining table, not really being sincere in their negotiations. So we decided to do a work slowdown. In a factory that looks like just meeting your quota and nothing more. It would mean something different at the Lusty Lady. It meant dancing, being naked, being on stage, wearing high heels, wearing makeup, but not doing explicit poses. And that's really what people came there for. We did this work slowdown, and one of our coworkers got fired.

As soon as she got fired, someone ran to the stage and said they fired her. We all just kind of immediately hit the streets and picketed. We had never done a picket before. We didn't even have a union contract yet. It was very spontaneous, and we just knew that we had to be in solidarity with her.

What I really carry away from that is that power of acting in solidarity with one another and having each other's backs. We shut down the theater, and we did get our bosses to come to the bargaining table. That's just a very contained episode, but what I take away is that there's a tremendous power in solidarity and in collective action based on common cause.

And that you don't have to be the sort of quote unquote "person who protests" to get involved.

I was young, I was in my 20s. I was just kind of grungy kid. We all were sort of outsiders. We were mad and we just acted. And then the next day we were out there picketing with our scraggly little girls in fishnets and ripped shirts, and then people just came walking up the hill.

We were on Telegraph Hill, and I was like, "What are these grown-ups doing?" People from the San Francisco labor council, I guess, had put out a call that some sisters on a picket line needed support. And so all these city workers and bus drivers and nurses, people with what we would have said "straight" jobs from the other world just were like, "Our sisters need our help and we're going to help them." Firefighters came by and their firetrucks and would like honk their horns for us. It was like "We have your back, and we're not gonna let people shame you into silence." It was so powerful.

Often the narrative about strippers is so polarized. You get people who say that being a stripper is the most feminist thing in the world and so empowering. It's not that simple; adult entertainment can be unbelievably exploitive. This book is a very good example that many things can be true at the same time. Being a dancer is a way for women to make money and to take agency. But it is also still a job.

I've always been of a few minds about that question, and I really tried to capture that ambivalence in the book. I talk a lot about the ways in which I found it empowering, particularly how I admired the women I worked with and the way that they carried themselves and the power they wielded over the men in that space.

At the same time, it's a strange kind of power. You don't have it anymore once you're not, you know, 22. There's inherently a sexism in that power. It's about about occupying a particular position in a patriarchal economy. Whenever someone has money and you need it, that person is going to be in power to some extent.

If your work can be framed as this cool, empowering thing, then that's seen as compensation enough. You don't need to make that argument about any other workplace in order to be justified in claiming your rights as a worker. But sex workers are kind of forced to make that argument.

It even got used by our bosses in negotiations. They wanted to have something about the job being fun and creative or something in our contract. And we were like, "That's bizarre to put that in a union contract. What it suggests is it's fun and therefore we don't have to pay that much. We don't have to give you decent working conditions or job security, because it's just fun.

On the other hand, the critiques of the industry and of stripping and other kinds of sex work, I don't always see those same critics examining other institutions like marriage or motherhood. I don't see people looking at those with as harsh a microscope as they do the sex industry.

As you said in the book, there were a lot of people doing sex work in the '90s in San Francisco. The AIDS crisis was starting to abate, and people started to feel safe again about exploring sexuality. We're in this moment where touch, once again, is so scary. What do think that's going to mean going forward in how we express that, in terms of commerce and entertainment?

I don't know where it's going to go. I know that people working in the industry now are really thinking about it. By the '90s, it was clear how AIDS was constructed and how you could be safer. COVID-19 is contracted a lot more easily, and sex isn't the only thing that's become dangerous. I wonder if peep shows are are going to come back. The workers that I've talked to recently are using online platforms now. That's been increasingly popular for 20 years or more, but some of the workers are really migrating to these online platforms.

I think that this is introducing its own set of organizing issues and opportunities for workers. When you're organizing, mostly you try to do that through face-to-face conversations with your colleagues. If you're not working face-to-face, that that becomes really a challenge. But sex workers are finding other ways to organize and they're finding ways to work that does protect their safety, mostly in online platforms. There are women in Portland who made a drive-through strip club. They made these little stages in their parking lot and girls are on these stages, dancing in gas masks. The industry will persist and hopefully, the people working in it will continue to organize. And it does seem that, from the people I've talked to, they are doing that, which is great.

Shares