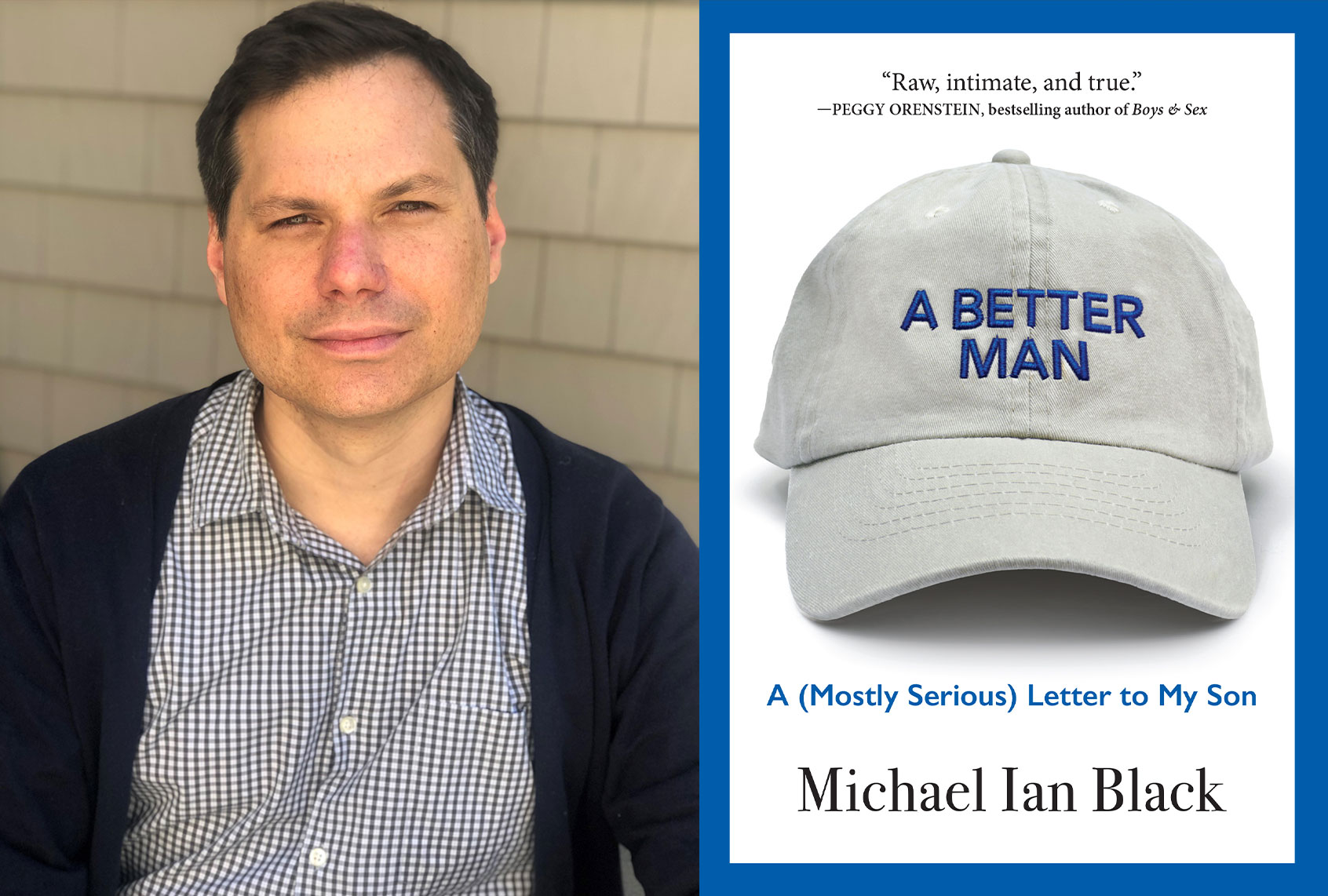

Masculinity isn’t inherently “toxic.” Yet within the current necessary cultural reckoning about inequality and abuses of power, the complicated issues around what it means to be male right now have been harder to define and discuss. So when Michael Ian Black’s son was preparing to leave for college, the actor, director and author decided to write him a message. The result is new book called “A Better Man: A Mostly Serious Letter to My Son.”

You may know Black more for his roles in the “Wet Hot American Summer” series, “Burning Love,” “Reno 911!” or maybe just his Twitter feed than his gender studies, but it’s his experience as a dad that lends to his credentials.

Black recently appeared on “Salon Talks” to discuss the tragedy that inspired the book, feminism and being “a guy often known for talking about Cabbage Patch Dolls on VH1.” Watch my episode with Black here, or read a Q&A of the conversation below.

This conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

You’ve written about your family and your experiences with fatherhood before. Now, as your son was turning 18, what made you say, “This is a moment where I want to tell a particular story right now”?

There were a lot of events leading up to it. He was in his senior year of high school. He was going to graduate. He was going to leave home. Like any dad, I was feeling somewhat sad about that, and hopeful about that. Then in the winter of that year, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas shooting happened in Florida.

I’d been paying a lot of attention to gun violence over the last many years since Sandy Hook, which happened when my kids were in elementary school and happened about 10 miles from my house. When Marjory Stoneman Douglas happened, I just started asking the obvious question, which had never really occurred to me before: Why is it boys who are doing this? Not just these big, horrible shootings, but the day-to-day violence that we see so often in our lives. It’s almost always boys. Why?

You say that in the book, it’s always someone’s son, because it’s always a boy. That’s a very humanizing and empathetic way to come into this conversation.

It was hard to look at the faces of all these boys and young men who were committing these crimes, and not see the obvious parallel that I have a son who looks a lot like them. Most of these crimes, the big shootings like that, they’re almost always white. Why? What is going on? I’ve wrestled for years with losing my own dad when I was 12. I never had conversations about manhood with him. I wanted to just give my son something that might be useful for him as he heads out into the world.

You bookend the book with these shootings, which is a powerful choice, because there are so many ways into a conversation about masculinity and manhood and boyhood. I guess it’s because that is also what is now defining Gen Z, in a lot of ways.

These things are becoming a more common. We saw these sorts of shootings happen pre-COVID, on average, once a day. I say in the book, “They’re as common as sunsets,” and they are, in this country. It’s inexplicable in so many ways, and also explicable in so many ways. A lot of it is rooted — in my opinion — in the way we think about boys and men and masculinity. This book isn’t about gun violence, but it definitely relates to it.

You also go into a conversation that’s hard for a lot of us to have, which is about the other side of that. What happens when we use phrases like “toxic masculinity”? What happens when we start demonizing an entire gender? You talk about your own experiences with that growing up. What effect did that have on you, hearing those kinds of messages as a kid, this implication that “male” is bad?

I grew up in a lesbian household. My mom and dad divorced when I was five or six, my mom was involved with another woman. They considered themselves pretty ardent, and at times strident, feminists. That phrase “toxic masculinity” didn’t exist then, but the phrase that did was, “male chauvinist pig.” They loved to describe pretty much all men as male chauvinist pigs, not realizing that between them they were raising three boys in the house, who were hearing this on a daily basis. Its effect was, for me, really corrosive. It made me mistrust men in general, but also kind of mistrust myself a little bit, and mistrust who I was as a boy, and then as a teenager, and young man. The effects of that were really lingering. On the flip side of it, it did force a kind of introspection about gender that I may not have had otherwise. Maybe I was more receptive to thinking about these topics than I might have been without that, but on balance, yeah, it was sh*tty.

It’s not easy to bring up the problems that boys have, that white boys have, that white men have in our culture right now. There’s not a lot of empathy in that regard. I love that you got blurbed by Peggy Orenstein who wrote a beautiful book that takes on a lot of the pressures and the problems, and the mental health issues that boys are facing right now.

An amazing book called “Boys & Sex.” I’ll plug her book. I’m happy to.

You’ve dealt with trolls before, you are not afraid of getting backlash on the internet. But to start that conversation where you say, “How can we have a more empathetic and kinder conversation around gender in general?” what were you thinking going into this?

I was very reluctant to go into it. I really was. Writing a book about this topic happened in a very organic way, and in a quick way, because it started with the Marjory Stoneman Douglas shooting. I wrote a Twitter thread about it. Then the New York Times asked me to write an op-ed about it. Then a publisher asked me to write a book about it. It happened very quickly and I was very reluctant to do it for a lot of reasons. One, I didn’t feel like I was qualified. I didn’t feel like I had any business sticking my beak into this particular puddle. I’m not an academic, I’m not a historian. I’m not a gender theorist, but I felt like, you know what? I’m a dad. These things are important to me as a father, and as a man, and maybe I could contribute something just from the perspective of that. Of a kind of run of the mill, boring suburban dad.

But I didn’t want to get on a soapbox. I didn’t want to say that I’m a better dad than anybody, or certainly a better man than anybody. I’m very upfront in the book about my flaws and faults and the ways I struggle. And I worried about being serious. I’m a comedian by trade, and I worried about whether anybody would be receptive to hearing word one from me; a guy often known for talking about Cabbage Patch Dolls on VH1.

So for all those reasons, I was reluctant. I wasn’t afraid of the Twitter trolls. I wasn’t afraid of any of that. I was afraid that I would get enough things wrong, that I would upset the people that I really want to support. I was worried, and continue to be worried, that maybe I’m getting things about women wrong, or that I didn’t include enough — hardly anything about the trans community, about people on sort of all parts of the gender spectrum. But I also didn’t want it to be a kind of catch-all for everybody. It is a letter to my son. There’s a lot that I worried about and a lot that I continue to worry about, but I’m getting more comfortable, having written the book, talking about these things and fully admitting, I don’t know everything. And please tell me where you disagree with me.

Part of the book really is your own reckoning with yourself, with your father, with your own life. In doing that and going back and revisiting your own life, were there things about it that surprised you? Were there things that you then took a second look at it and said, “Oh, wait a minute. Now that I’m this age and I’ve reached this point in my life, I see things really differently”?

I came from a background that had no relationship to the arts or anything like that. I made a career for myself in the arts. I always sort of prided myself, stupidly, on being different because I was off being an actor and whatever. What really got driven home for me, in particular with writing this book, is how I am exactly like so many other men. In some ways, I’m exactly like my dad, who I always thought of myself as so different from. We share the same emotional reticence. We share the same difficulty, sometimes, in communicating who we are, and what we want. We have the same reticence asking for help. These are unfortunate cultural norms for all men. I stupidly thought I had kind of escaped them. I hadn’t. That’s just me. I’m that guy. I may be better at acknowledging it than other guys, but it’s as embedded in my DNA as every other American dude.

When you were starting out, were you going to people you know and saying, “Who do I have to read? What do I have to understand? What is the beginning of this conversation for me, so that then I can have this conversation with my son?”

It was a wild goose chase of ordering things from bookstores, of casting a very wide net in the beginning, and just seeing what was out there. It was surprising to me how little there was, that was written from a kind of everyday perspective about masculinity. Things that weren’t academic, things that weren’t rooted in gender theory, for example, or sociology or history. There just wasn’t. That conversation just wasn’t happening in a kind of mainstream way. I read a lot of the history and the sociology and the gender theory, and loved it.

I feel so indebted to feminism, and I think I’m developing a much better sense of what it means. A richer sense of what it means. When I grew up in a feminist household, it meant something very different and it meant something very abrasive to me. I always thought of myself as a feminist, because it just felt like that’s the right thing to be, you know? But it definitely came with a really hard tinge to it, and a kind of serrated edge that I felt like it was nicking me a lot of the time. And I think, in this broader cultural understanding of what feminism is, that’s still true for a lot of people, which is why so many people reject it, men and women.

The antagonistic labeling that it has.

I think that’s true. Any social movement that’s bucking up against the status quo has to develop that edge, by necessity, because you’re trying to cut away at something. It took me a long time, and I think I’m still wrestling with my relationship with feminism, to feel comfortable inhabiting it in a way that I feel like I do now. But I think for a lot of guys, that word, “feminism” immediately turns them off because it implies that to be a feminist, you therefore have to be feminine, and it doesn’t allow guys to kind of step forward into really looking at what it means. What does it mean to ask for, or to demand equality? They don’t tie that equality to say, the civil rights movement, or to any other movement for equality. Feminism is threatening to a lot of, I think, people who would be otherwise totally sympathetic to it.

You use the scarcity model. If there’s “too much” feminism to go around, there’s an implied scarcity for men. Those ideas about empathy and vulnerability you can find embedded in other books that are about empathy and vulnerability; they’re not really male specific. It becomes very difficult to tease that out of where it is in the conversation.

The books that I found that are written on this subject are generally written by women. For good reason; women are crying out for men to be more empathetic, and to be more vulnerable for very good, pragmatic reasons: first and foremost, their own safety.

Your book is really about kind of the branding issue that we have around masculinity, and feminism. I’m curious now we’re at this moment, where there are aspects of our culture that are really putting the “mask” in masculinity. What have you been watching and noticing during this pandemic, that you want to talk to your son about?

It’s been amazing to watch the top leadership in our government fully embracing everything that I think is wrong about masculinity, spearheaded by the guy at the top. It comes down to this same argument that I talk in my book, about how masculinity is about creating a sense of invulnerability, because to allow yourself to be vulnerable is to demonstrate weakness. And weakness is traditionally antithetical to masculinity. Even when it comes to something as elemental as saving your own life, or saving the lives of people around you, the impulse is to reject the thing that is proven to be helpful in that regard. It’s more masculine to go, “I don’t give a sh*t about this plague” than to go, “I care about myself and my family and the well-being of others.” The fact that those two thoughts should co-exist equally, and that one should be considered more masculine is ludicrous. But we’ve got the guy in charge who so fully inhabits that anachronistic sense of masculinity, that it’s literally killing people. He’s literally killing people. He’s holding these rallies where he’s basically saying, “If you wear a mask, you’re kind of a pussy.” It would be absurd if it wasn’t so tragic.

When you’re looking at these Gen Z kids going to vote in the presidential election this year, what is it about now, your son and your daughter, that gives you hope?

So much. I’m somebody who believes that every generation is the same generation. We label generations, I think somewhat foolishly. Every generation has every kind of person in it.

What I see from kids in my children’s generation is a lot of anxiety first and foremost, for good reason. But also a much greater awareness of the world and their place in the world than I had when I was their age. A lot of them, I think, are showing a tremendous desire to be helpful. Maybe that happens with every generation that the young people are idealists, and want to be helpful. At the very least, I see it with this generation too. I see a lot of good kids. I see a lot of young people who are really trying, and want to be good and are cognizant of the way that the culture is changing around them, and aren’t resisting it as strenuously as maybe people in my generation and older are. Even if they’re not leading the change — and my kids aren’t thought leaders in any way, shape or form — they’re aware of what’s going on. And I think they want to be helpful.