In 2016’s “USS Indianapolis: Men of Courage,” Nicolas Cage battled sharks. Perhaps he learned from them how some species must keep moving to survive. Throughout his long and varied career, Cage has kept swimming. The waters – and the roles — just keep getting wilder.

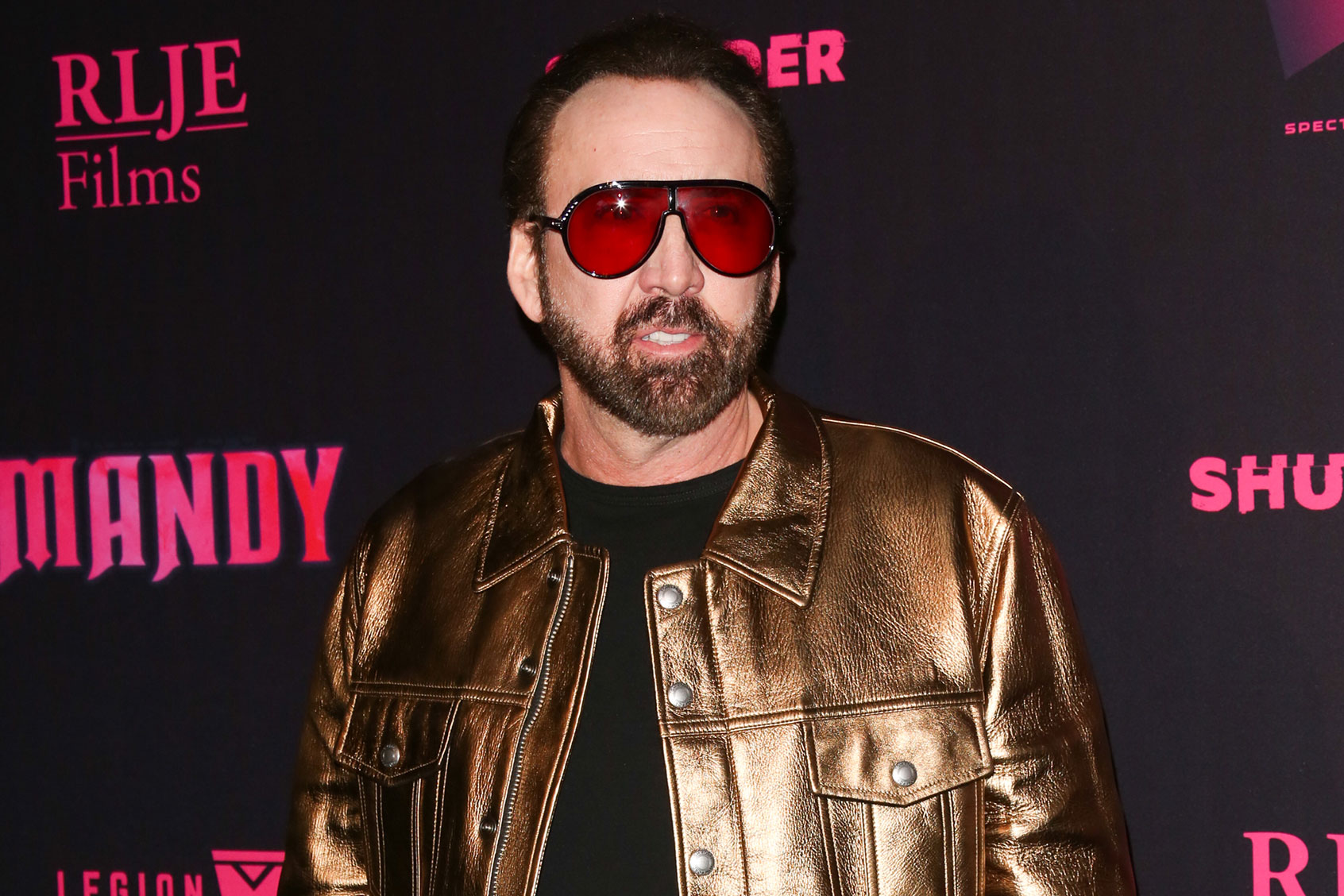

It’s been a weird ride for the actor, both onscreen and off, from geeky heartthrob to action star to direct-to-video slump to . . . wherever he is now, currently staring as none other than the actor Nicolas Cage in the meta flick “The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent.” To survive as an artist, you must change. But I earlier in his career I didn’t think much about Cage, dismissed him as prolific if not especially moving, until one film above all showcased his bloody power, not only for rage but for love: “Mandy.”

In fact, in “Massive Talent,” Cage’s superfan Javi Gutierrez (Pedro Pascal) makes sure to single out “Mandy” as well. Even though Javi cites John Woo’s 1997 action thriller “Face/Off” as his favorite film from his idol, he acknowledges that “Mandy” is underrated.

RELATED: Give in to Nicolas Cage’s “Massive Talent,” a clever caper with the power to make anyone a fan

Famously, Cage was born into a show biz family, the nephew of Francis Ford Coppola and cousin of Sofia Coppola and Roman Coppola. He changed his last name, as writer Joe Hill, son of Stephen King would, to avoid accusations of nepotism, after begging his uncle Francis to give him a screen test as a teenager. Cage based his stage name on Marvel superhero Luke Cage and on composer John Cage.

James Dean inspired Cage to act, and in early performances, Cage has a kind of floppy-haired nonchalance, as if this business of acting is easy, no problem. And then there’s “Mandy.”

It’s a world of trust and safety they’ve built with each other — and it’s temporary, of course.

It’s hard to explain Panos Cosmatos’ 2018 film, co-written by Cosmatos and Aaron Stewart-Ahn. It’s either your kind of thing — or it’s not. “Mandy” is another world both close to and very far from our own. The film is divided into parts: The Shadow Mountains, Children of the New Dawn and Mandy. I wish I could live in the first part. But all of us who are not men live in the last. Cage walks through all three with ease.

Set “circa 1983 AD” in a forest that could be the Pacific northwest, the film starts with Cage as Red, a soulful logger. Red’s live-in romantic partner is Mandy (Andrea Riseborough, who is haunting), an artist who works in a backwoods store by day and by night, reads and draws fantastical illustrations. Mandy’s interested in astronomy, and she and Red share a love of science fiction. They watch a sci-fi movie, joke about Galactus.

They also seem to share violent pasts: Red may be an alcoholic in recovery, and Mandy survived a childhood marked by an abusive father.

The couple live in a many-windowed house that glows at night, pulsing with light and steam like a greenhouse. Or, like the chambers of a heart. They don’t have curtains. They live in such a remote place that Mandy leaves the door open. In a premonition of violence, Red wonders if they should move away, go somewhere different. But Mandy refuses to give up “our little home.”

One of the worlds of “Mandy” is the world of the lovers: an isolated, rich embrace. The first part of the film drips with the richness of nature like a Maxfield Parrish painting: hills of pine, skies with clouds that have the eerie green rinse of just after rain. Red and Mandy sleep surrounded by windows. They boat on an emerald lake — Crystal Lake — that dissolves into a shot of flames: a campfire. It’s a world of trust and safety they’ve built with each other — and it’s temporary, of course.

Mandy catches the eye of a man.

Jeremiah disrobes before a captive and drugged Mandy after playing one of his songs for her — a kind of “Frampton Comes Alive!” for the cult leader set.

A failed musician and burgeoning cult leader: Jeremiah Sand (the incredible Linus Roache). The world of Jeremiah is that of a run-of-the-mill narcissist masquerading as the messiah. He has a handful of followers in a “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” van. And like Father Yod and Charles Manson (he even calls Red and Mandy pigs), he has an album. Jeremiah’s world includes a lot of drugs, keeping his followers in a haze and free love for him only. His hair and makeup look like Iggy Pop left in the rain, and he alternates between wearing a Luke Skywalker robe and tight Jimmy Page pants with a cross necklace. He’s an easily wounded, mediocre man.

But like the world of the lovers with its Galactus, the world of the Children of the New Dawn, Jeremiah’s cult, has its specific language too including the Horn of Abraxas, a kind of moon rock used to summon a biker gang Jeremiah hires as muscle, and a knife described as the “tainted blade of the pale knight, straight from the abyssal lair.”

Phrases like these sound like a marriage between heavy metal and LARPing — and with a certain tone, it would be funny. It is funny. And when Jeremiah disrobes before a captive and drugged Mandy after playing one of his songs for her — a kind of “Frampton Comes Alive!” for the cult leader set — she has a natural, honest and simple reaction. She laughs.

As the apocryphal phrase, attributed to Margaret Atwood, goes: “Men are afraid that women will laugh at them. Women are afraid that men will kill them.”

In this world of men, humiliation is unforgiveable. Women only occupy a few roles in Jeremiah’s mind; after all — he has merely two female followers: a crone (Olwen Fouéré, who is mesmerizing) and a maiden — and deviant is not one of them. Mandy becomes the only other thing a woman can be if she’s not sexual: a witch to burn.

For all its red mist and LSD eaten like peanut butter, “Mandy” is ultimately a film about love.

Mandy already doesn’t fit in. Neither she nor Red are young, and they don’t have children — aspects I love about them as a couple. She makes art, reads, walks in the woods alone. She doesn’t wear makeup, and she has mismatched pupils and a long, jagged scar on her face that is not explained; she simply has it. She’s lived through a lot, Mandy. But not this.

Red is plunged into the world of grief, grief as I’ve never seen represented so accurately, so painfully, onscreen. It’s embarrassing, keening, real. It’s absurd, as death always is, and the last part of the film is the heavy metal world of blood vengeance. Red has his own named weapon too, the Reaper, and he forges another: a silver ax. Things get pretty medieval with a knight and beheadings as Red travels a landscape of tunnels and jagged cliffs like one of Mandy’s drawings come to life. And if you think Cage isn’t the one to dispatch a bike gang, you don’t know Cage.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Despite the wildness of the film, it stays grounded thanks to its specificity. Nothing seems out of place — not a telepathic chemist, not a tiger, not the best chainsaw scene since “Evil Dead” — because this the table that has been set for us.

In my work as a fiction writer, people always ask about world-building. The truth is two things: It has to be real for you and it has to be very specific. You have to choose stark elements and stick to them, refer to them the same way every time. It’s the sticking, the consistency, that makes a world real. So, “Mandy” invents a sci-fi novelist — whole, vibrant pages from her trade paperback — and a TV commercial for a brand of demonic mac and cheese. It’s the ’80s on an alternate timeline, maybe the Berenstain Bears one.

It also reinvents Cage, reborn as a gentle man with burning, divine vengeance running through his veins, believable as no mere accidental action star, but a psychedelic folk horror hero. “Mandy” set the tone for Cage transformations to come, the soulfulness of “Pig,” the casual desperation of “Willy’s Wonderland,” fully harnessing Cage’s depths not only for mania but for quiet suffering.

Because for all its red mist and LSD eaten like peanut butter, “Mandy” is ultimately a film about love, and how wicked this world can be. And that makes it our world, very much indeed, and the one to walk through it, wielding a blood-stained ax, bringing you home (at least in his nightmarey dreams) is Cage.

“Mandy” is currently available on demand.

More stories like this:

- The peculiar mystery of Nicolas Cage’s favorite pasta shape

- Forget the final girl, “Texas Chainsaw Massacre.” We’re ready for the final woman

- Nic Cage: The genius of the full-throttle freak