“I know how to control a room,” says Paula Stone Williams. “I’m an alpha.” It’s a confident statement, the kind of thing that women — especially older women — aren’t often heard to say. What’s her secret? A long life of leadership, as a pastor, speaker and educator, no doubt. And also, by her own admission, male privilege.

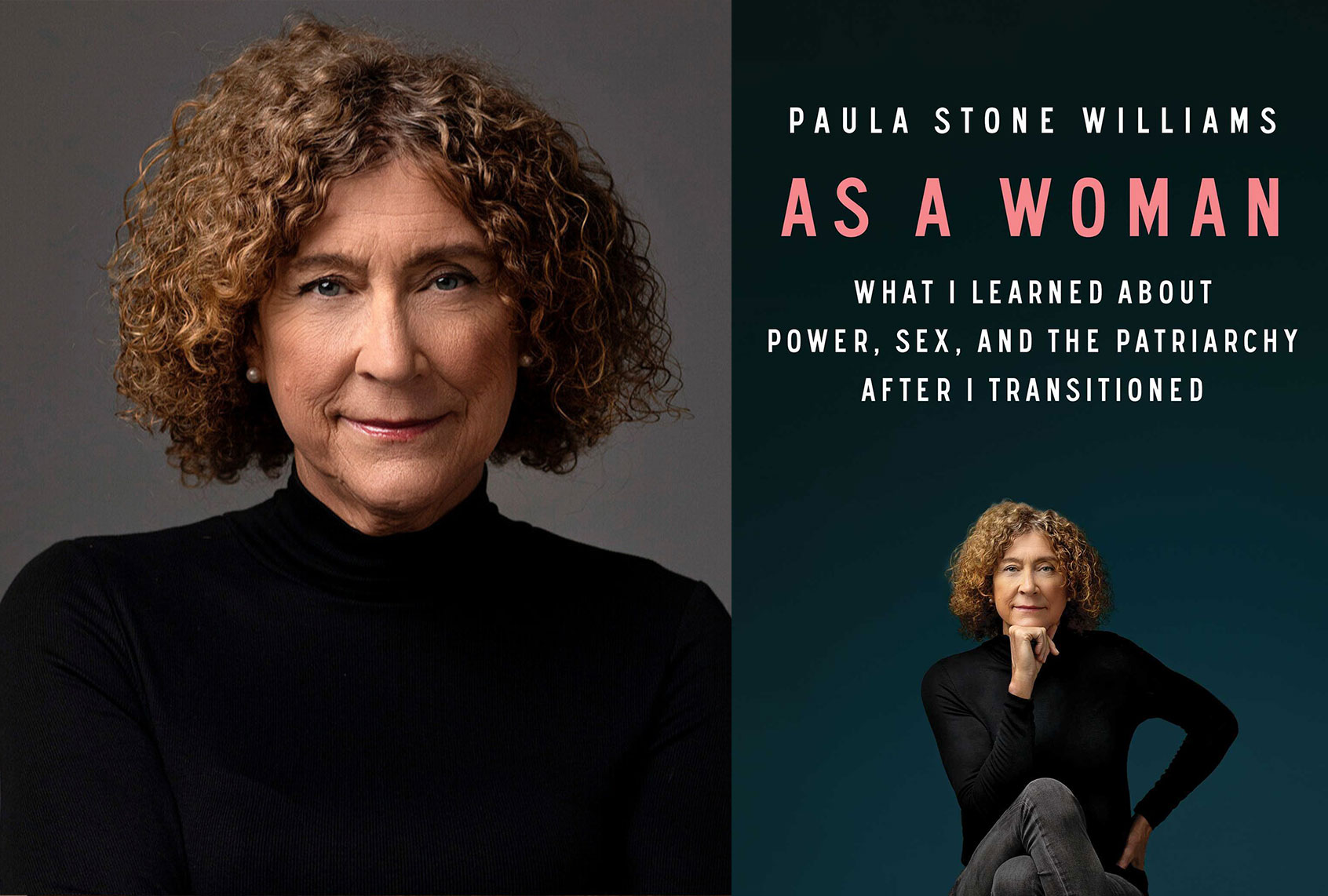

In her candid memoir, “As a Woman: What I Learned about Power, Sex, and the Patriarchy After I Transitioned,” Williams writes about her evangelical upbringing, her decision to come out as transgender in her 60s and what she discovered about masculinity when she began showing herself to the world as a woman. It’s a frank exploration of one individual’s journey to authenticity, and a hopeful case for a kinder version of Christianity. Williams appeared on “Salon Talks” recently to talk about God, testosterone and the calling she couldn’t ignore.

You can watch the “Salon Talks” interview here or read a transcript of it below.

The following interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Your book speaks to everyone, but it has a very special resonance for those of us trying to walk a spiritual path while also holding true to our progressive values. This has been a real story of your own journey. You open the book with a very beautiful poem by your friend Nicole Kelly Vickey. Tell me about that poem.

I had asked Nicole to help me. She wrote that poem for me, and when I first began reading the book for the audio version, I just wept all the way through it. I just kept weeping and weeping, because it’s so beautiful and poignant, and for me it produced within me such a deep desire to get upright.

I think that there is often an understandable need in our culture often to be respectful of a trans person’s identity and to not refer much to the person’s past gender expression. You go in a different direction. This book is about what it felt like to walk around the world being seen as and treated as a man. Why was it so important to you to tell the story that way, and to not just close that door?

I was well-known in the evangelical world, and I couldn’t just disappear into the night. I also felt a strong sense of setting right what I had not set right in my previous life. I was totally LGBTQ+-affirming in the 1980s, but I remained within an evangelical denomination because I thought it was okay to change it from within. When I look back on it now, that was an awfully convenient position to take for a powerful white male and I wish I had come out sooner in terms of being LGBTQ+-affirming. I don’t think I was ready to come out as transgender sooner, but I recognize that there’s a need to just tell my story.

I’m also terribly concerned about the incredibly difficult divide that we’re facing in our nation right now. How do we bridge that divide? I’m convinced that the only way we truly bridge the divide is one story at a time. We’re a narrative-based species. You don’t sleep without dreaming and you don’t dream in mathematical equations. We dream in stories. So I thought, if I tell my story beginning to end, maybe some of the people from that world will read it because right now it’s actually that evangelical world that is the strongest against the transgender community. 84% of evangelicals think gender is immutably determined at birth, and that’s actually pretty frightening. They’re the ones driving the several hundred anti-transgender bills that are pending in various states right now.

More bills than ever before. Despite more visibility, more representation, we also have more pushback, more oppression, more anti-trans bills than we have ever had.

It’s fascinating to me that everyone just assumes that these are all Republican legislatures and so this is a Republican issue. Actually it’s not. A study done of Trump voters in 10 swing states asked, “Should transgender people have the same civil rights as everyone else?” 60% of them said yes. It’s not so much a conservative issue as it is primarily an evangelical issue.

You talk about “the call,” and many of us who are familiar with the vocation aspect of that word. You also talk about the call to identity. How do you see those parallels in your life, having been called to ministry and having been called to be your most authentic self?

I’m not sure what the origin of a call is. In fact, I say that in the book. It was my call from God. I don’t know. I know it came from a place so deep that it frightened me. I think that is the universal call. I love the way Joseph Campbell identified it as the hero’s journey. An ordinary citizen is called on an extraordinary journey on the road of trials. Initially, they reject that call because hey, it’s the road of trials. Then a spiritual guide, a Yoda, comes into their life and finally gives them the courage to answer that call. I believe a call is inherently spiritual, but I would separate spirituality out from any particular religion. I think we are spiritual beings and I think we do during our lives experience multiple calls, which is a deeper voice speaking to us.

If you’re Jungian, you might call it the collective unconscious. If you’re Christian, you would call it the Holy Spirit. But I think whatever the source is, there is a voice that speaks to the deepest part of ourselves that both terrifies us and calls us forward. I know I have clearly felt that voice heard that voice only three times in my life.

There’s a phrase you use in the book, a more expansive view of Christianity. How do you see your relationship with God, with faith now? It would be very easy, given what you have been through, given what you have heard from other people, to say, “I’m out, God, thanks.”

A lot of people find that fascinating. I speak all over the world, primarily on issues related to gender equity, usually to corporations. When we come to Q & A, you would expect the questions to be related to gender equity, and the majority of them are. But always someone says, “Why are you still in the church after the church treated you the way it treated you?” I always love answering that question, because religion is not fundamentalism. If you take a look at the fundamentalist expressions of all three desert religions — Christianity, Judaism and Islam — all three are still religions of scarcity. The way all three of those religions began is, “There’s not enough resources to go around and we’re going to take care of our own.” But if you look at the more generous expression of all three of those religions, you find that they are not religions of scarcity.

For me, working out spirituality is better done in community. We’ve been doing it in community for eons. I was reading Jonathan Haidt’s book, “The Righteous Mind,” not terribly long ago. He was talking about the development of our species, and said that we really did not take off until we left the level of blood kin and moved into the level of tribe or community.

He said that what it is that brought us together into communities was not the need for safety, but it was man’s search for meaning. I think it’s better when we search for meaning and community. I think we were designed, if that’s an appropriate word, to search for meaning in community. For me to come back into the religion in which I was born and try to work out my spirituality in this new body is appropriate. I didn’t think it would be to lead a church; that was another one of those things. It was a sense of call, first back to the church and then to lead a specific church.

I think what a lot of us return to is this sense of higher and unconditional love.

I really believe that’s exactly what it’s all about. I say this in our church all the time. In Jesus’s very last day of public ministry, he’s asked which of the laws is the greatest, he says, “Hey, it’s just three things, loving God, loving neighbor, loving self.” And then it says, “From that day on no one dared to ask him any more questions.” They realized it really was that simple and also that impossible. Love all of our neighbors, and maybe the hardest of all, love ourselves. And I don’t think you can love others if you don’t love yourself.

There is a difference between feeling female on the inside and being treated female on the outside. What was that like? What has surprised you about the female experience?

The thing that surprised me the most was really just being unaware of my male privilege. I brought a lot of privilege with me when I transitioned, a lot of decades as a minister. I know how to control a room. I’m an alpha personality. And yet in just seven years as a woman, I cannot believe how much confidence I have lost, how often I now say, “I’m sorry, but . . .” when I know I’m right. I end up apologizing for it. In my very first TED talk, I said, “You don’t have to apologize for being right,” yet I find myself doing that all the time.

I wonder though if you do, or else the person on the receiving end of that message won’t hear the rest of it.

Somebody asked me about that not long ago. I think that’s a wonderful point. I said, “You know, sometimes it’s just easier to get by. You can’t always be the voice that is fighting against injustice. Sometimes you just have to let it go.” I wish that I was strong enough to consistently say, “No, I know what I’m talking about.” It’s so frustrating to me to be treated as if I don’t know what I’m talking about.

I think one of the most frustrating was when I was dealing with a lot of liberal-minded people, all LGBTQ+, and we’d hired a new CEO for the organization. We have a large national conference and they were talking about having the CEO speak for the keynote. I said, “Well, she’s never really done much public speaking. It might be better if we just interviewed her. I’d be happy to do that, but if you want her to give a speech, I’ll be happy to coach her.” The well-meaning white male in the room said, “If we’re going to do that, why don’t we get a real coach?” I waited for someone to speak up and no one did. And what I wanted to say was, “Oh, okay, wait. I’ve done four TED Talks. I have coached TEDx speakers. I’m a speaker’s ambassador for TED. I’ve taught speech in three universities, two in the United States and one in Europe. Just help me understand what part of that does not make me a real speaker’s coach?” But I didn’t say anything because if I did, now I’m that woman. It was so aggravating to me.

You’ve also experienced a change in what it feels like to be intimate, and what maybe cis men don’t know about that.

I think testosterone is an incredibly powerful substance. I don’t care how thoughtful, how good, how caring a man you are, when it comes to sexuality, a little bit too much of your body wants to focus on that 10 seconds. It is in fact, a huge driver of human males.

As a woman, you realize actually it’s about the other 23 hours, 59 minutes and 50 seconds. It’s everything. Did we spend time together today? Was that deep conversation? It doesn’t have to even be really good conversation. That can be a huge disagreement, but it’s deep and intimate. What are the smells in the room? Are flowers involved? There are all of these things that create desire that have nothing to do or little to do with that biological drive that just seems so great for men.

I live not far from Rocky Mountain National Park and when I’m up there in the fall, you’ll watch the elk. You have an alpha male who’s always protecting his harem, and you see younger males come up and challenge him. I’ve watched it so often, I don’t watch the elk anymore. I watch the people watching the elk. It’s always so funny, because you see the men invariably start rooting for one or another with the alpha males, and their wives are hanging back chuckling like, “Oh, have we really evolved all that far as a species?”

It is fascinating to watch, and yet that was my biological drive. Thank God there’s a wonderful thing called civilization, so we teach our sons that you actually have agency and you don’t act on the fact that you want to have an entire harem that’s only yours that you will fight every other male for. It’s incumbent for us to help our sons understand that this is a natural biological tendency, so we have to be taught that we have agency regarding that. Now we have external things to help us do that, like the #metoo movement.

We live in a culture that is deeply sexualized and also deeply and profoundly shaming. You talk about all of the sexual obstacles you had to overcome from your own evangelical upbringing and you get to this place where you can see sexuality as this beautiful, transcendent, spiritual thing.

My friend Linda Kay Klein wrote a book called “Pure” about growing up in an evangelical subculture that shames your sexuality, and how much more shaming it is toward women than it is toward men. I certainly experienced shame in growing up in the evangelical world, but I did not experience it in the same way that my wife experienced it or that so many other women of that generation, even until just recently. There was such shame tied to sexuality, and I feel like it’s one of the greatest injustices that’s been perpetrated upon evangelicals by their purely patriarchal male leadership.

Just think about it. Whether it’s the Catholic church or the evangelical church, if you’re in a position of power, you want to make sure you remain in power. Let’s just maybe narrow it down to the Catholic church. As a priest, maybe I’ll be the only one who can forgive sins. So how do we then make sure that everybody knows they need their sins forgiven? Oh, let’s choose the universal thing, sexuality, and maybe we’ll pick on something like masturbation. I will call that a sin for which you need to be forgiven because then we can be guaranteed we’ll be employed forever. All of these poor kids in confession booths for centuries just for being human. It’s really tragic.

It’s truly tragic and it is truly about control, specifically patriarchal control.

It’s not something that actually is inherent in the text, from a Christian perspective. It didn’t really begin to show up until Augustine in the fourth century.

You recently celebrated a benchmark birthday. What are you learning from your younger peers, the people who come to you with information and also with questions? What has this younger generation of the LGBTQ+ community taught you about living in this world and coming into it openly later in the game?

I love seeing how much they’re willing to explore their identity at the age of which we should be exploring our identities. There was a study came out not long ago that said that 62% of those who identify as gender nonbinary were between 13 and 26 years of age. Well, of course they were because that’s the age where we should be exploring our gender identity. Will they still be gender nonbinary when they’re 52? Who cares? The important point is that they’re able to explore how fluid gender is, that we’re all on a spectrum and that spectrum goes from what is traditionally very masculine to traditionally very feminine and everything in between.

When I look at the numbers traditionally, we’ve been saying the 0.58% of the population as identified as transgender. In young people, I saw not long ago that somebody said it’s 2.8%. That to me is something to be celebrated, not because more people are transgender than were before, but because we finally have an environment where exploring one’s gender identity is just fine. I look at my five granddaughters, who are all between 10 and 13. It took them 30 seconds to adjust to my transition. It’s just a normal thing to them. The fact that I’m trans is incidental for this whole generation. The fact that someone is trans or nonbinary is incidental. I think that’s marvelous.