Here’s a confession that I’m still a little ashamed of: back in college, I once got voted as “Most Likely to Bag on Asian Guys.”

It was graduation season, which made everyone a little nostalgic for the inanities of high school and its superlatives, and so my friends put together their own award show for the disembarking seniors. Next to the usual plaques for “Best Hair” and “Cutest Couple” were novel ones that reflected our snark and particular cultural milieu as a heavily Asian-American and white group of overachievers: “Worst Driver” became a toss-up between the only two people with cars on a campus marked by walkability (coincidentally, both also Asian); “Most Likely to Marry Asian” went to a white guy who exclusively dated girls from Southern China and was unafraid to use this line to explain to me why we could never be together. (If the motherland was a rooster, my hometown — Nanking — hails from its belly, and this apparently was disqualification enough.)

I’m not going to lie; “Most Likely to Bag on Asian Guys” captured the general ethos I held about my race for most of my life. As the kid who spent every other year of elementary school in a different town (San Juan, Puerto Rico; Ames, Iowa; College Station, Texas) with no other Asians besides the members of my family, I spent my nights watching American television with my parents in a joint and concerted effort to learn English.

“Golden Girls” and “Married . . . with Children” were our favorites, but occasionally a public broadcast for a dated movie or miniseries would make it into the mix. The characters occupying the 24-inch screen before us varied, but one thing stuck: American men — and by that I meant white men — were a different species from the men I knew at home. White guys professed their love often, bought flowers and gifts whether they were rich or poor, gave their women rings and hugs and words of affirmation, kissed in public.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

I asked my father why he didn’t do these things for Mommy. He laughed and shrugged and went back to work. So I took things into my own hands. In fifth grade I took my lunch money and walked to Conroy’s Flowers on the corner of Anza and 190th. I bought three carnations. The white gentleman behind the counter smiled at the small change in my small hands and promised, “I’ll dress them up nice for you.” He added baby’s breath, a few greens and cellophane on the house.

I skipped home with the bouquet and handed it to my father. “Give these to mommy,” I suggested (or was it a command?). He did, and I was happy; as immigrants, we could fake it till we made it with the best of them.

The following Christmas, I asked my father to take me to Kmart during their going out of business sale and led him to the fine jewelry counter. I pointed at a 1 carat cubic zirconia solitaire, brassy and yellow. “Mommy needs an engagement ring,” I told him. “How much?” he asked the woman behind the counter. I don’t remember what she said but I know exactly what drawer that ring is in in my parent’s bathroom today, because every time I visit I check on its whereabouts. My mother has never worn that ring in her life but no matter; every time I see it in its faded blue box, a little part of me simmers with hope — although for whom, I cannot say.

My successful streak at turning my Chinese father into the kind of white man I saw on TV abruptly ended when one day, I politely asked him to pick my mother up. Like a baby, I clarified, when neither of them understood what I was saying. I grabbed a Cabbage Patch kid and simulated the scooping movement I saw on television when lovers found themselves in the heat of passion. They laughed in a way to suggest that I was too stupid to deserve an answer. I went into my room and vowed that I’d never marry a man who couldn’t carry my own body weight with ease and finesse; physics be damned. Based on the anecdotal evidence before me, I figured that my best chances of achieving this was with someone white, and therein my own romantic prejudice was born.

By college, this racism against my own had metastasized; whenever the topic of boys came up, I’d explain to the girls in the room, “I only like white/Black/Latino guys.” I spent the rest of college crushing on various shades of white — although two Asian guys and a hapa guy infiltrated that mix when I wasn’t paying attention — and it wasn’t until I got that award plaque that I considered the possibility that the problem lay with me, and not Asian men.

I went to the only Asian professor in my major — a thick-accented Chinese man named Kaiping — and said I wanted to do my senior thesis on why Asian girls like white guys so much. Being a good scientist, he opted not to take offense at my question and helped me design a series of psychological studies that tested this theory. Three years later, halfway through graduate school, its findings became my first publication; it turns out, I was not alone. There are even fancy terms for this phenomenon: self-stereotyping, in-group derogation, or the most succinct and accurate — racism.

Interestingly, Asians like myself appear to take the lead on the phenomenon; as with math and filial piety, we’re overachievers when it comes to prejudice too. Everyone is ethnocentric, but leave it to us to take it one step further and turn our racism inward, against ourselves. We’re not the only ones, of course. But somewhere between the double eyelids stitched by man (or lotteried by God) on every translucent-skinned female celebrity hailing from the East and the proliferation of Asian wives coupled to white men in America (myself included), our Eurocentrism seems par for the course, a hereditary feature of our Asian heritage, more of a birthright than an acquired taste.

These days, I spend my hours teaching undergraduates that psychologists have come up with an elegant model — called the stereotype content model — to capture its flavor profile: if all our prejudices can be determined by our perceptions of two dimensions — a) their warmth, and b) their competence — then Asians unanimously occupy the low warmth-high competence category. People respect our academic prowess and STEM skills but otherwise do not see us as particularly nice or pleasant; classic stereotypes of the so-called “inscrutable” Chinese or ninjas or dragon ladies or any of Lucy Liu’s onscreen personalities attest to this.

But here’s what I’ve never managed to solve: my own capacity for gendered racism. And once again, as all the studies on implicit bias — or a quick scan of America’s current racial reckoning — proves, we are far, far way from a post-racial utopia.

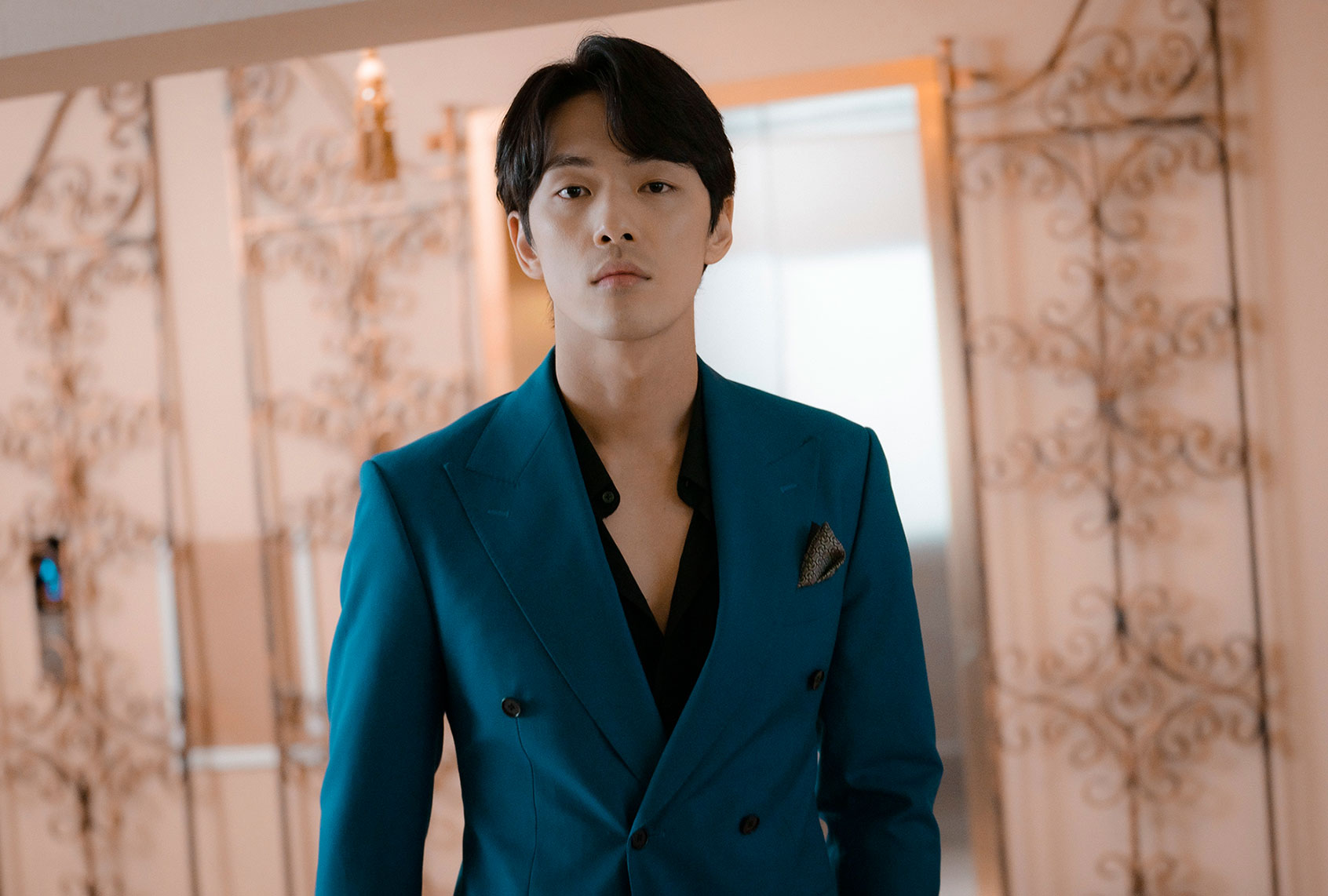

Son Ye-jin as Yoon Se-ri and Hyun Bin as Captain Ri Jeong-hyeok in “Crash Landing on You” (Lim Hyo-seon/Netflix)

Son Ye-jin as Yoon Se-ri and Hyun Bin as Captain Ri Jeong-hyeok in “Crash Landing on You” (Lim Hyo-seon/Netflix)

The other day, though, I found a serendipitous way to counter my own biases when my supremely white mother-in-law called my (also white) husband and refused to shut up about how spectacular Netflix’s Korean drama, “Crash Landing on You,” was. It was even better than anything she had ever seen come out of Hollywood, she declared.

Curious, the two of us logged in to Netflix and spent the next three days reading the small white text parading across the television screen, glued to a story we had not heard before and could not turn away from. In the series, North Korean soldier (Hyun Bin) falls for a South Korean socialite (Son Ye-jin) who accidentally crosses the DMZ while paragliding during a windstorm. However, their love is the kind that survives multiple murder plots, traitorous families, cultural differences and class divides.

As I tell my students, storytelling at its best is nothing sort of sorcery; the greatest stories we can’t help but remember and retell and be changed by. In my case, K-dramas became the perfect antidote against the perpetual stereotypes of Asians perennially competent but never quite as warm or likable. Because if there’s anything shows like “Crash Landing on You” are good at, it’s having audiences fall for just about all the Koreans in the cast (and not just Hyun Bin either, whose apparent magnetism appears to rival God’s).

Maybe this is why representation matters: loving a fictional character is the gateway drug for cherishing the real people they represent. No matter that these dramas hide everyone’s pores and glosses over the hero’s benevolent sexism. I didn’t realize it until I saw it, but I’ve been waiting my whole life to see Asians on TV screens in America idealized to the same degree that white characters have always been privy to, where Asians men are not just competent but also sexy, and where Asian people across the board are not just useful but kind, funny, immensely interesting.

I doubt that all Korean men cry with the kind of poetic abandon their actors do on TV or go to great lengths to purchase scented candles for the woman they are pursuing. I also suspect that the netizens of Pyongyang don’t all dwell in the kind of idyllic villages whose quaint kimchi basements and neighborly investment in each other’s love lives makes up for whatever geopolitical divides exists between them and their Southern compatriots. But no matter: idealization is a privilege, and all the more so compared to invisibility.

When I turned on Netflix that day, I didn’t know that there was going to be a competition for hearts and minds (turns out, there always is). “Crash Landing on You” tasted so sweet going down that I didn’t realize its medicinal value in countering our old stereotypes about f**kability and want.

As for me, if I was ashamed of being crowned “Most Likely to Bag on Asian Guys” some decade and a half ago, I was even more embarrassed last week when I discovered that it took binge-watching an entire Korean drama to remember the immense desirability of men from my own group — and not just the Hyun Bins either — in all their imperfection and glory.

“Crash Landing on You” is streaming on Netflix (where you can also watch “Squid Game”).