Like many of my fellow animal-lovers, it pains me to think of killing an insect. There are videos of me as an infant staring in awe at creepy-crawlies as they scuttle past me; as an adult, I’ve retained that habit.

Yet like millions of other Americans, I make an exception for the spotted lanternfly. That is because I live in Pennsylvania, where the Asian insect is widely perceived as a threat to existing ecosystems — and, consequently, of local economic interests. In other places, people are warned of venomous spiders or so-called “murder hornets.” The only common theme is that, in the United States, we have a tendency to live alongside species that were brought here rather than initially coming from here.

Indeed, globalization and mass migration of people — and goods — has accidentally sent all kinds of different critters and plants to parts of the world where they shouldn’t be. This has resulted in the spread of “invasive species,” meaning an animal or plant that is both not native to an ecosystem where it currently lives, and also either causes or is likely to cause significant harm to local wildlife or to the nearby humans.

Harm, in the latter case, can be physical, economic or both.

Invasive species are introduced by any number of means. Most of them are accidental, such as when ballast water spreads aquatic species from one continent to another, or when insects burrow into wood that is transported from region to region. Others are deliberate, such as irresponsible exotic pet owners abandoning their former companions or even acts of misguided idealism (including one, seen below, inspired by William Shakespeare).

Sometimes humanity and wildlife luck out and the introduction of these species proves relatively harmless. On other occasions, however, we’re not so lucky. These invasive species may look cute (in some cases), but they are scourges on American ecosystems — which is why conservationists are trying to eradicate them, sometimes with help from citizens.

Burmese Python (Getty Images/Hillary Kladke)

Burmese Python (Getty Images/Hillary Kladke)

First reported in the United States in 2000, Burmese pythons are among the largest snakes in the world. They are voracious carnivores, wolfing down a wide range of prey from birds and reptiles to amphibians and insects. Thanks to the exotic pets trade, Burmese pythons were introduced to the South Florida ecosystem at the turn of the century. They

compete for food with native fauna, at least when they aren’t actively eating the hapless critters. A 2012 survey found that the South Florida raccoon population had dropped by 99.3 percent and the opossums population by 98.9 percent. Quite often, raccoons and opossums were found in the pythons’ stomachs.

Zebra Mussel (Getty Images/Ed Reschke)

Zebra Mussel (Getty Images/Ed Reschke)

Nor is that the worst thing about Zebra mussels (if it was, they wouldn’t appear on this list). The bigger problem is that, ever since Zebra mussels were

introduced to the Great Lakes region in the 1980s (likely by European commercial ships), they’ve been

clogging pipes in ways that cost businesses millions. They also compete with native wildlife for food sources, particularly algae.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Spotted Lanternflies (Getty Images/arlutz73)

Spotted Lanternflies (Getty Images/arlutz73)

First seen in Pennsylvania in 2014, the spotted lanternfly is an attractive insect, with its moth-like wings and bright red body. Yet the spotted lanternfly has had a

devastating effect on the northeast, gobbling up vineyards and damaging the stock of Christmas tree growers. The tourism industry has also taken a hit: after all, nobody wants their wedding to be crashed by swarms of winged insects.

Even casual homeowners and pedestrians aren’t safe. The spotted lanternfly is wont to spit out what one entomologist described to Salon as a “sticky honeydew.” Black sooty mold will grow on this, which is both dangerous if accidentally ingested and quite slippery if you’re unfortunate enough to walk on it.

Joro Spider (Getty Images/David Hansche)

Joro Spider (Getty Images/David Hansche)

We are often told not to judge others by their appearance, and yet humans often don’t follow those words of wisdom.

This is evident in our reaction to the next invasive species on this list, the

Jorō spider. One might assume that they are a major threat given that the spider is (a) venomous, (b) as big as your hand and (c) contains a dizzying array of exotic colors on its shell.

Yet this is simply not true. The spiders rarely attack humans and, if they do, their fangs are too short to penetrate our skin. They do not seem to be harming local ecosystems in any major way. Their biggest “threat” is that they create large webs which are easy to accidentally walk into.

Expert opinion? If you see a Jorō spider, leave it alone.

Asian giant hornets (Getty Images/kororokerokero)

Asian giant hornets (Getty Images/kororokerokero)

When singer-comedian Weird Al Yankovic wrote a song about 2020 appropriately titled

“We’re All Doomed,” he referenced “murder hornets coming from across the sea.” In the pandemic-addled zeitgeist, the public imagined waves of killer stinging insects threatening them even as they stayed indoors to avoid COVID-19 infections.

While this nightmare scenario never came to pass, the

so-called “murder hornets” still pose a threat to humans. Their sting has been described as “like a hot nail” and kills an estimated 50 people every year in Japan, where they are common.

First detected in the United States’ Pacific Northwest in 2019, the bigger problem with Asian Giant Hornets is that they target bee colonies. Bees are already declining at a perilous rate, and Asian Giant Hornets are making that situation worse.

European Starling (Getty Images/Susan Walker)

European Starling (Getty Images/Susan Walker)

In William Shakespeare’s play “Henry IV, Part 1,” Hotspur famously proclaims that he will give a European Starling as a gift because it “shall be taught to speak.”

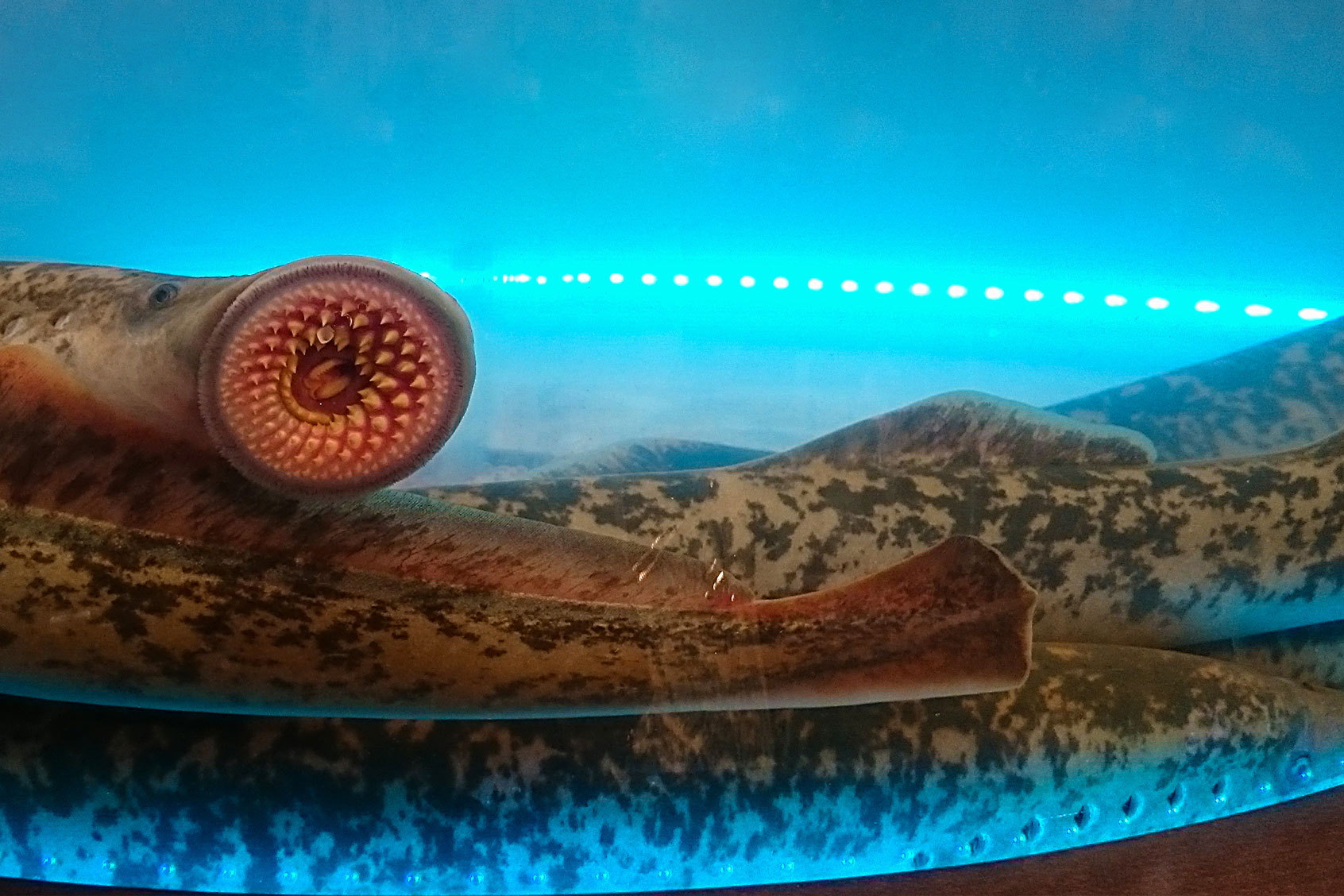

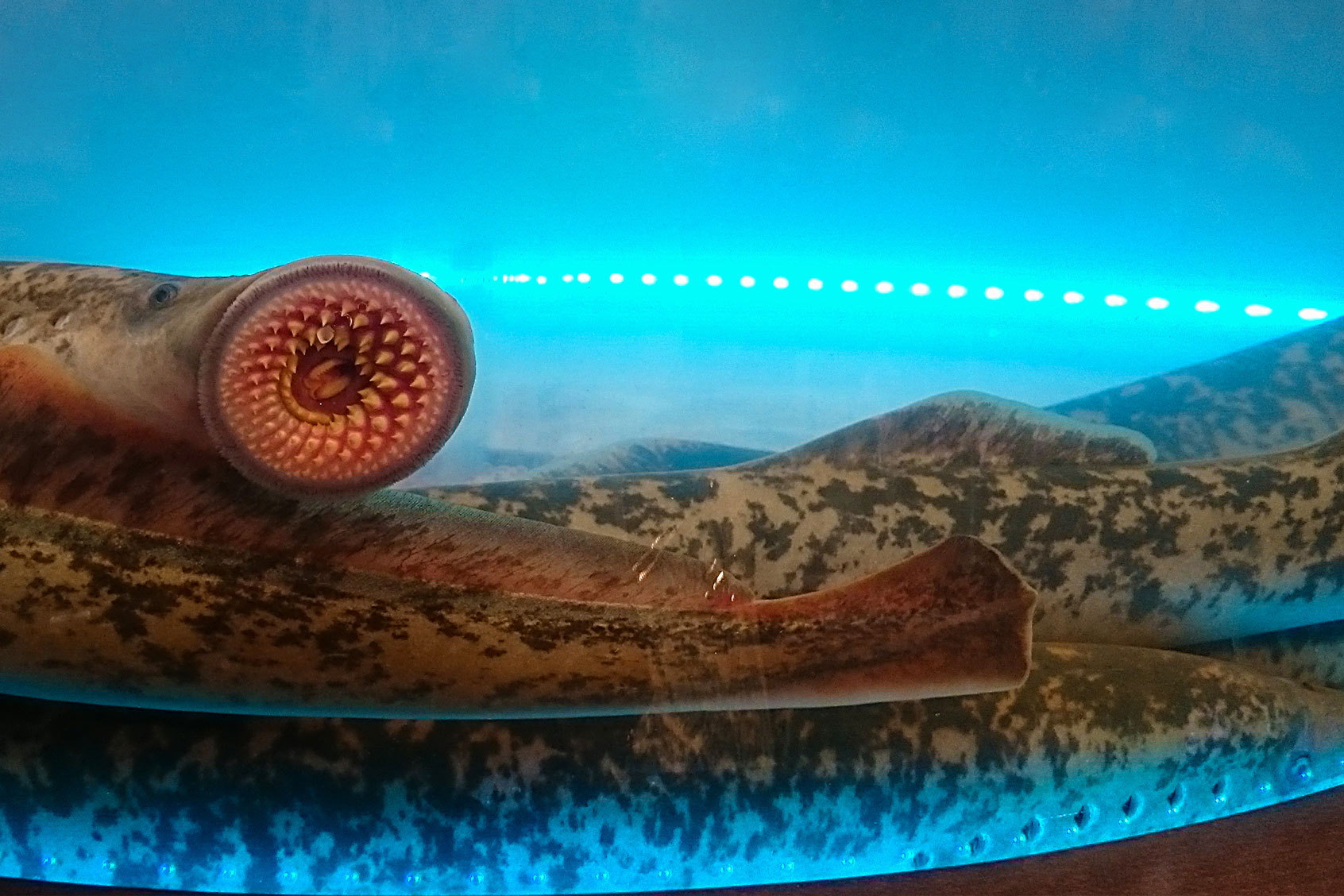

Sea Lamprey (Getty Images/Jramosmi)

Sea Lamprey (Getty Images/Jramosmi)

Great Lake lampreys are one of the oldest of America’s invasive species, as they were

first detected in the Great Lakes in 1835. Yet do not feel sympathy for them just because of their longevity. Whenever sea lamprey populations spike in the Great Lakes, the local fishing industries get hit extremely hard. Entire species of fish are wiped out by the voracious bloodsuckers.

The

pandemic only made this worse, as longstanding programs that existed to control the sea lamprey population had to be suspended due to the lockdown. Sea lampreys are definitely flourishing in the Great Lakes area today, although it remains to be seen whether the problem is as severe as it was in the 1940s and 1950s.

Read more

about the environment

Burmese Python (Getty Images/Hillary Kladke)

Burmese Python (Getty Images/Hillary Kladke) Zebra Mussel (Getty Images/Ed Reschke)

Zebra Mussel (Getty Images/Ed Reschke) Spotted Lanternflies (Getty Images/arlutz73)

Spotted Lanternflies (Getty Images/arlutz73) Joro Spider (Getty Images/David Hansche)

Joro Spider (Getty Images/David Hansche) Asian giant hornets (Getty Images/kororokerokero)

Asian giant hornets (Getty Images/kororokerokero) European Starling (Getty Images/Susan Walker)

European Starling (Getty Images/Susan Walker) Sea Lamprey (Getty Images/Jramosmi)

Sea Lamprey (Getty Images/Jramosmi)