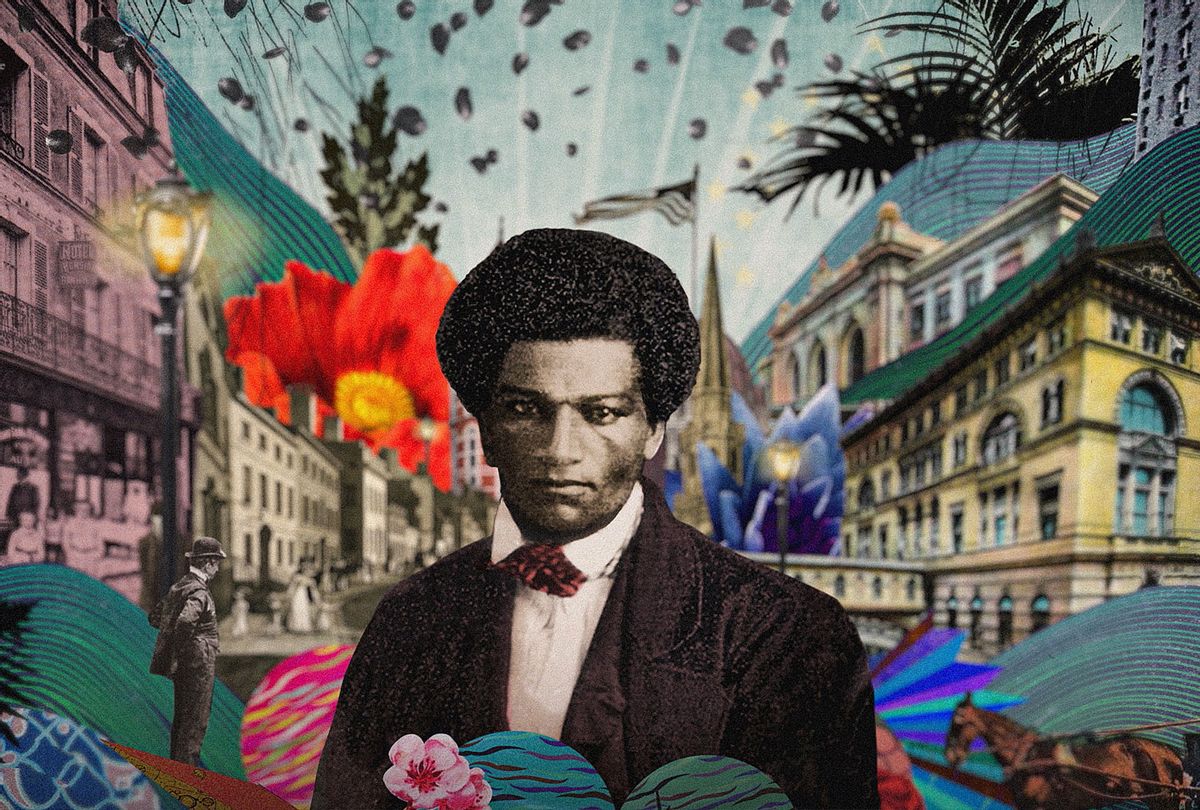

From teaching himself how to read to enacting what scholar Henry Louis Gates, Jr. described as "one of the most unusual escape stories in all of the literature about slavery," Frederick Douglass' life is worthy of its own feature. He designed it to be seen as such, molding his celebrity in part by becoming the most photographed Black man of his time.

Nevertheless, he usually shows up a co-star in documentaries about other 19th century leaders, as is the case in two recent Lincoln documentary series or the fictional series "The Good Lord Bird."

"Frederick Douglass: In Five Speeches" is a step toward remedying this, making Douglass the hero by way of his writings and impact on American history and bringing them life through the voices and observations of six prominent actors, including Jonathan Majors and Jeffrey Wright.

RELATED: "Abraham Lincoln" and "Lincoln's Dilemma" clarify a few things about uncomfortable history

These names are the ones with whom the mainstream audience is likely most familiar, owing to Wright's long career in film and TV, and Majors' central roles in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and on HBO's "Lovecraft Country." But I cite them here not for those reasons but due to the way this hour channels Douglass' prose through their personal identities as keepers of his legacy.

They are also Black American men living the future for which the famous orator and abolitionist fought, and they demonstrate an acute understanding of what it means to be his inheritors.

Through them, Douglass' grandeur and passion echoes across the ages to resonate in our era.

These performers do not mean to sanitize his activism or make him more palatable to those who would whitewash his legacy by leaving out the sections of his speeches that may make weaker souls uncomfortable. Majors sets that tone at the top of the hour with the following quote from Douglass' designated 1847 address, "Country, Conscience, And The Anti-Slavery Cause."

"I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism," he says plainly. "I have no country. What country have I?"

Gates, who executive produces this hour directed by his "Finding Your Roots" collaborator Julia Marchesi, appears as one of the primary academics in the piece alongside David Blight, whose Pulitzer Prize-winning biography "Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom" inspired the special.

Through each of the chose speeches the audience is invited to consider a period in Douglass' extraordinary life.

People who may recall at the very least the edges and outline of his story likely read at least segments of his bestselling "Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave." For a time it was on the required reading list in a number American elementary and high schools; nowadays, who knows if it'll survive the current spate of book bans?

Andre Holland (Courtesy of HBO)

Andre Holland (Courtesy of HBO)

The production calls upon Andre Holland to deliver excerpts from that defining 1845 work, including Douglass' familiar recollection of how he learned the alphabet thanks to the benevolent ignorance of the Maryland woman who enslaved him.

This becomes the chorus, with the speeches serving as verses walking us through the man's life through his varied but never-shifting views on equality, emancipation, and America's hypocrisy in calling itself the land of the free while chattel slavery remained legal.

Each of the selected speeches highlights Douglass' singular ingenuity and focused conviction, starting with Denzel Whitaker's recitation of "I Have Come To Tell You Something About Slavery," writing in 1841, followed by Majors' slow burn into searing brimstone during his piece.

Colman Domingo performs "The Proclamation And a Negro Army," Douglass' 1863 response to the Emancipation Proclamation calling for Lincoln to allow Black soldiers to join fight against the Confederacy.

Wright's piece, 1894's "Lessons of the Hour," has a ruminative quality appropriate to the sentiment in which Douglass created it, as a man who pushed a president to legislate liberation for his people but who also lived to see the rollback of Reconstruction and the continued barbarism to which white Americans subjected Black citizens. It is one of his final observations on America's inability to live up to promised liberties its founders envisioned for all people.

That these speeches are performed by Black men matters. It imbues the words with an extra weight that is not lost on the viewer or those channeling Douglass' words. As a bonus, each shares his reflections on what the 19th century agitator's thoughts mean to him today. Majors' takeaway is particularly poignant after his thunderous interpretation of this passage:

. . . here are men and brethren who are identified with me by their complexion, identified with me by their hatred of Slavery, identified with me by their love and aspirations for Liberty, identified with me by the stripes upon their backs, their inhuman wrongs and cruel sufferings. This, and this only, attaches me to this land, and brings me here to plead with you, and with this country at large, for the disenthrallment of my oppressed countrymen, and to overthrow this system of Slavery which is crushing them to the earth.

"When he says that it's crushing them to the Earth, that's when I went, OK, well, that's brother Floyd, you know that is that image," Majors observes. "And it's not a new thing. It just made me want to say those words to people, for the people who couldn't."

Nicole Beharie (Courtesy of HBO)Anchor these speeches to a deeper profundity is Nicole Beharie's delivery of Douglass' 1852 opus "What, To The Slave, Is The Fourth Of July?" which Blight, in his concise analysis, likens to a symphony with three movements. Beharie, the sole woman in the special troupe of actors, translates the irony of Douglas speaking about Independence Day to the all-white Ladies Anti-Slavery Society for modern audiences with a simmer that eloquently builds to a furious boil.

Nicole Beharie (Courtesy of HBO)Anchor these speeches to a deeper profundity is Nicole Beharie's delivery of Douglass' 1852 opus "What, To The Slave, Is The Fourth Of July?" which Blight, in his concise analysis, likens to a symphony with three movements. Beharie, the sole woman in the special troupe of actors, translates the irony of Douglas speaking about Independence Day to the all-white Ladies Anti-Slavery Society for modern audiences with a simmer that eloquently builds to a furious boil.

It might be lost on some viewers that this rendition comes to them from the star of "Miss Juneteenth," but even if that is the case, the rightness and righteousness of Beharie's ownership of this section is undeniable.

In the spirit of centralizing its performers, the producers also call upon quilt portraitist Bisa Butler and poet Nzadi Keita to contextualize Douglass' life, including his flaws and questionable acts, along with all uplifting the courage and determination in his prose.

"I think the more human we make our heroes, the more noble they become," Gates says after Keita points out how relatively unseen and unmentioned his wife Anna Murray remained as he rocketed to national fame.

Any worthwhile documentary doesn't shy away from its subjects' warts; this one brings only enough attention to Douglass' to acknowledge his mortal imperfections. None of it takes away from the might and purpose of each performance in this special that at long last, and appropriately, recognizes Douglass starring role in our nation's story.

"Frederick Douglass: In Five Speeches" premieres Wednesday, Feb. 23 at 9 p.m. on HBO and will be available to stream on HBO Max. Watch a trailer for it, via YouTube.

More stories like this:

Shares