Since his death in March of 1982, Philip K. Dick has become recognized as one of the most significant figures in contemporary science fiction. He's published 44 novels and over 100 short stories on a multitude of sci-fi themes dealing with everything from space exploration and time travel to alternate history, telepathy and the effects of psychoactive substances. This range is one of the reasons Dick continues to win new readers.

It also doesn't hurt that numerous of his works have been adapted into successful Hollywood movies and TV series, all of which were released after his death, with the latest being the mind-bending stories that make up Netflix's anthology series "Electric Dreams." (Adult Swim's 2021 animated series "Blade Runner: Black Lotus" is an original spinoff.) With such a large body of work, this certainly won't be the last and it would seem that his influence will only continue to grow into the future. Foremost among these adaptations is, of course, Ridley Scott's cult classic adaptation, "Blade Runner," released on June 25, 1982 — a mere two months after Dick's death.

These latest Nexus-6 models are also equipped with real artificial intelligence, making them "more human than human" as Tyrell extols ... This is where things go awry.

Set in a Los Angeles of November 2019, viewers are pulled into Scott's one-time future by Vangelis' magnificent electronic score in an iconic opening scene featuring an ominous cityscape draped with smog and cut through with flame bursting from towering smokestacks in a sky travelled by flying cars. It is an opening scene that is far different from the one Philip K. Dick employed to introduce readers to his dystopian future in "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" which was also in San Francisco. Scott's film also places the main conflict pitting Deckard against a band of rebellious androids in an opening text crawl rolling up the screen, establishing a slimmed-down dystopian context for his cinematic story world, which just turned 40 in June.

While Dick's novel contains the same general story viewers see in "Blade Runner," Scott does not include any mention of Mercerism, while also eliminating the relief and intrigue provided by the uncanny talk show host, Buster Friendly, as well as Deckard's wife, Iran. Instead, Scott concentrates his focus more fully on the questions raised by human ingenuity and technological progress as represented by the Tyrell Corporation, which parallels the Rosen Association of the novel. The corporation was founded and operated by a genius bioengineer, Eldon Tyrell, who has made himself into a god in the mold of Dr. Frankenstein. Instead of necromancy, however, he uses advanced technology and bioengineering to produce advanced cyborgs that are stronger and smarter than most humans and work Off-world in performing a myriad of dangerous and hazardous tasks.

The problem, though, is that these latest Nexus-6 models are also equipped with real artificial intelligence, making them "more human than human" as Tyrell extols. A feature allowing these so-called Replicants to synthetically develop independent thought, to form memories, and have emotion. This is where things go awry. The combination of these human capacities is what also allows for empathy and self-understanding, leading them to revolt against an existence in which they have been condemned to serve as servants and tools of colonization in worlds beyond. Thus, creating the necessity for blade runner police units, with Harrison Ford in the lead role of Deckard, whose job it is to "retire" the rebelling machines.

Films featuring robots ... represent a lament for the loss of a world that existed before the advent of such personally invasive technologies that seem constantly at work in eroding our privacy, personal freedom and agency.

While November 2019 came and went without the apocalyptic scenario offered in "Blade Runner" coming to pass, although Elon Musk tried his best to riff on the movie with the flop unveiling of the Cybertruck, it's not as though scientists and engineers have disavowed the aspirations that may one day lead to the invention of technologies Scott's film presents his viewers with, either.

Sean Young smokes in a scene from the film 'Blade Runner', 1982. (Warner Brothers/Getty Images)

Sean Young smokes in a scene from the film 'Blade Runner', 1982. (Warner Brothers/Getty Images)

The theme of killer robots that animates Dick's novel and Scott's film can be traced back to the Czech writer Karel Čapek's 1921 play, "R.U.R." ("Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti"), in which the term "robot" was originally coined. From this auspicious example in which robots are created to serve as factory workers of optimal efficiency, they are then quickly adapted into emotionless soldiers, all while becoming self-conscious. It's not a far leap from there, of course, to the robots assessing their lot and realizing that they may not need humans, of whom they are superior, anyway. The trajectory contained in Čapek's story were subsequently expressed in a long list of other texts and films, as well, from Isaac Asimov's "I Robot" to Stanley Kubrick's "2001" and Michael Crichton's "Westworld," to more recent films that have extended "Blade Runner's" message in the "Terminator" and "RoboCop" franchises, Alex Garland's "Ex Machina," "Automata" and "Chappie," along with episodes in Charlie Brooker's "Black Mirror" and Tim Miller's "Love, Death & Robots."

Films featuring robots, many of which express concerns that speak to the deep-seated suspicions, anxieties and fears that people harbor about the perils of technology, also, perhaps, represent a lament for the loss of a world that existed before the advent of such personally invasive technologies that seem constantly at work in eroding our privacy, personal freedom and agency. All within a historical context in which so many seem dependent upon, if not addicted to, technologies essential to daily life. This is precisely the essence and reflection of what has become known as the posthuman era, which Katherine Hayles saw as typified by the union of the human being with intelligent machines.

In the future-present both the novel and film depict the wealthy elite and politically connected have long since fled our dying planet, as an ad promoting off-world living proclaims, "a new life awaits you in the Off-world colonies!"

Scott's "Blade Runner" is also striking for its stylized apocalyptic and dystopian backdrops and fashion in a world in which only the unfortunate masses — and the corporations whose neon signs are ubiquitous — remain. In the future-present both the novel and film depict the wealthy elite and politically connected have long since fled our dying planet, as an ad promoting off-world living proclaims, "a new life awaits you in the Off-world colonies!" A chance to begin again in a golden land of opportunity and adventure. And who doesn't want that, right, especially after we've mucked up the worlds we currently live in?

The issues raised and critical question posed gets us back to what lies at the heart of "Blade Runner." Not whether Deckard lives happily ever after with Rachael (Sean Young), or whether he is a Replicant himself, but to the more fundamental status of technology in relation to human life.

This is the issue that lies at the crux of the Replicant leader, Roy Batty's (Rutger Hauer) response to his creator, Tyrell, when asked, "Would you . . . like to be upgraded?" Batty's response, "I had in mind something a little more radical," hints at the nature of his discontent. He follows this up, saying simply, "I want more life, father," in demanding a reprieve from the failsafe four-year lifespan that he was built with. It is a statement that speaks not only to his desire to be freed from his slavery to Tyrell and to time, but an independence from the control of humanity itself. A prospect that Tyrell knows as well as we do, will steer us inexorably to a condition in which humans are an obstacle, and weak, emotional and obsolete ones at that. The idea conveyed in this exchange and sanctified in Tyrell's death at the hands of his prodigal son exposes the ironic basis of human dominion over machines and does little more than reflect our own insecurities and weakness in the face of forces that we fear we have lost control over.

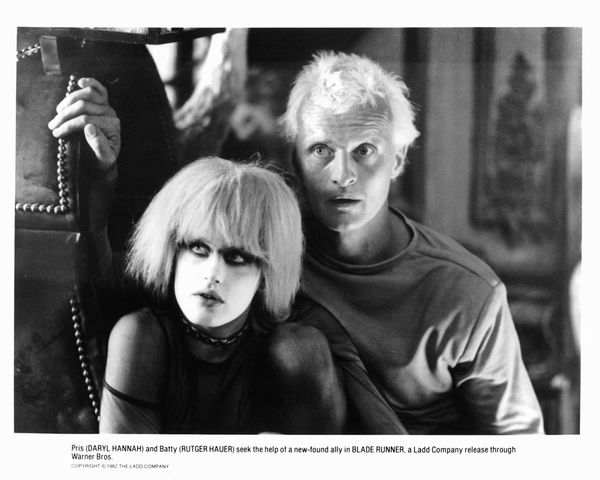

Daryl Hannah and Rutger Hauer in a scene from the film 'Blade Runner', 1982. (Warner Brothers/Getty Images)

Daryl Hannah and Rutger Hauer in a scene from the film 'Blade Runner', 1982. (Warner Brothers/Getty Images)

With these philosophic musings in mind 40 years since the film's release, we may now consider not just what the beneficial uses of machine learning, Artificial Intelligence, and robotics may be, but more emphatically for whose benefits and to what ends. Looking around at the status of such applications today, whether at the prospect of ever more realistic and submissive sexbots, which was what Batty's Replicant companion Pris (Daryl Hannah) was created for as a so-called "pleasure model," Tesla's continued development of self-driving capabilities including that armored Cybertruck equipped with standard bullet-proof windows, the future, indeed, looks bright, and with all the sarcasm of the "Black Mirror" bullet hole logo.

We may now consider not just what the beneficial uses of machine learning, Artificial Intelligence, and robotics may be, but more emphatically for whose benefits and to what ends.

And this is not even to mention the even more ominous developments in the military application of robotics and drones such as in the U.S. Marines development of a program dubbed Sea Mob testing self-navigating unmanned boats that can be equipped with .50 caliber machines guns. And we have all seen news stories detailing the devastation that has been unleashed by drone aircraft deployed by the U.S Airforce throughout the Middle East. Given these boats and aircraft represent only the tip of the spear with the ongoing efforts of military contractors to create other "lethal autonomous weapons," the examples offered in "Blade Runner" now seem more relevant and urgent than ever.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Perhaps we are already past the point of no return. And not just because a significant cross-section of the population has seemingly lost faith in our political system and courts, while being marginalized and disempowered due to the accumulated effects and pressures of social inequality. Or simply disconnected and disaffected out of sheer apathy and boredom, and with millennials cast as convenient scapegoats. And then, all the others disgusted and discouraged by an overwhelming sense of hopeless despair at the extent of the corruption, greed and dishonesty that is now shamelessly put forth as a replacement for the American ideals of justice and equality, and the myth of the American Dream.

So, when we get to "Blade Runner's" climactic confrontation between Deckard and Batty in which the Replicant is clearly the superior combatant, it is vital that Batty – not Deckard – is the one who reminds us of human ethics and morals in stating, "Quite an experience to live in fear, isn't it? That's what it is to be a slave." It is in this moment that Batty lays bare a history of humanity in which greed, exploitation and violence have become not just a means to an end, but a means in itself.

This, while the famous scene in which Batty acknowledges the end of his lifecycle in accepting the fleeting, ephemeral nature of memory and existence, poetically stating, "All those moments will be lost in time . . . like tears in rain." But it's not a statement of resignation by a rogue or malfunctioning machine, but a mirror held back up to Deckard, and all of us. One that reflects a different conception of life and being in the world. An experience in which the responses of apathy and escapism are fatal in a world that demands our engagement, and especially with others, if we are going to ever make this world, our world, a place for all, and that is worth living in.

Read more

about our new robot overlords

- The "Black Mirror" oracle: Confronting the technology we desire that could also destroy us

- Assimilate us, "Westworld": With humanity this horrible – onscreen and off – just let the robots win

- David Bowie, Elvis and "Blade Runner": A fan theory to end all fan theories

- Automated "killbots" are a popular film trope. Will they soon be a reality?

Shares