By now, most people understand that “cultural appropriation” usually refers to the exploitive consumption of ethnic and marginalized cultures by others. We’ve seen non-Black personalities wearing cornrows. Or celebs like Olivia Rodrigo and Awkwafina use what they think is AAVE – accents and dialects of Black cultures, like Jamaican accents – as a way to show they’re hip within their own cliques and with Black people.

The term could apply to specific foods, a style of dance or the celebration of a religious holiday. Whatever it is, the common factor that shifts the adoption of a cultural artifact from mere appreciation to appropriation is not honoring and even erasing its origins – all while celebrating its “new” form as desirable. Just look at how Black people are still mocked and stigmatized for our hairstyles, but then Bo Derek or a Kardashian is praised for sporting those same styles.

But what does all of this have to do with Korean dramas?

As fashions and musical styles like Afrobeats can be appropriated, so too can television and movies. How does the phrase “cultural media appropriation” sound? I think it can be used to describe how American studios and networks have been acquiring South Korean and other content from East Asia to adapt for audiences in the United States.

RELATED: The fall of Ricky Gervais: How did the once-brilliant star of “The Office” end up here?

But wait . . . isn’t that just adaptation? Countries around the globe have been adapting each other’s films and television shows for years. There are British adaptations of American shows (“Law & Order: UK”), American adaptations of British shows (“The Office”), South Korean adaptations of American shows, Japanese adaptations of South Korean shows, Taiwanese adaptations of Japanese shows, etc. But what I’m speaking about isn’t the fair cultural exchange of media like the aforementioned examples.

Instead, I’m referring specifically to how Hollywood seems to be making a concerted effort to focus on South Korean – as well Japanese – content, for the sole purpose of remaking the stories to appeal to American audiences, i.e. white audiences. I say “white audiences” because it can’t be denied that from the casting and dialogue to the stories and even costuming, the experiences of white people take precedence onscreen in Hollywood.

American filmmakers look East

Martin Scorsese, winner for best director for his work on “The Departed,” poses with his Oscar at the 79th Academy Awards in Hollywood February 25, 2007 (ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)This trend is something that I’ve been paying attention to for years, starting with “Infernal Affairs,” the 2002 Hong Kong crime drama directed by Andrew Lau and Alan Mak about a cop (Tony Leung) who goes deep undercover in an infamous Hong Kong triad led by a ruthless gangster (Lau), who in turn infiltrates the police. The film became a sensation, earning nearly $9 million worldwide, drawing universal critical acclaim for its nuanced character work and even spawning two more films to become a trilogy.

Martin Scorsese, winner for best director for his work on “The Departed,” poses with his Oscar at the 79th Academy Awards in Hollywood February 25, 2007 (ROBYN BECK/AFP via Getty Images)This trend is something that I’ve been paying attention to for years, starting with “Infernal Affairs,” the 2002 Hong Kong crime drama directed by Andrew Lau and Alan Mak about a cop (Tony Leung) who goes deep undercover in an infamous Hong Kong triad led by a ruthless gangster (Lau), who in turn infiltrates the police. The film became a sensation, earning nearly $9 million worldwide, drawing universal critical acclaim for its nuanced character work and even spawning two more films to become a trilogy.

Its global popularity didn’t end there. Martin Scorsese’s award-winning 2006 film “The Departed” is a remake of “Infernal Affairs” starring Matt Damon and Leonardo DiCaprio as the undercover moles. Despite its clear roots, there was no mention of “Infernal Affairs” or the efforts of its creators during the multiple “Departed” Oscar acceptance speeches. To me, this is a sign of white people being unwilling to acknowledge the people of color whose work they use as “inspiration” to create adaptations for other white people to consume.

Normally I have no issue with adaptations when they’re done right, when the fundamental characteristics that make the originals entertaining and cherished by fans aren’t changed in such a drastic way that they’re almost unrecognizable. Among the many adaptations of East Asian properties that work is Robert Rodriguez bringing “Alita: Battle Angel,” based on Yukito Kishiro’s cyberpunk manga series, to the big screen in 2019. Despite some critiques, the film was praised for staying faithful to its source material, the multicultural casting and visual effects. Earning $404 million worldwide, it’s Rodriguez’s highest-grossing film to date.

Unfortunately, this seems to be one of the few exceptions to the rule of whitewashed adaptations.

One only has to look at the track record. To date there has been a plethora of American studio adaptations of anime, Japanese manga and animated shows and films, and every single one of them have been whitewashed, stripped of the cultural markers that speak to the countries and people who made them. Iconic properties like “The Power Rangers,” all “Godzilla” films and yes, “Ghost in the Shell,” which has become infamous for its whitewashing, particularly of the main character Motoko Kusanagi, who was given an Anglo name and played by . . . Scarlett Johansson, a white woman. “Death Note” and the notoriously bad “Dragonball: Evolution” are other examples of not only whitewashing, but also audience backlash that should serve as glaring caution signs to the powers that be, that viewers don’t want stories about people of color to be rewritten and told through the white gaze.

There’s also the odious film adaptation of “Avatar: The Last Airbender” by M. Night Shyamalan. Though the original animated series is an American production, it featured many characters of color who were whitewashed for the film with all but one of the main characters played by a person of color. Zuko (Dev Patel) just happens to be the villain and therefore reinforces negative stereotypes of Asians being portrayed as evil and untrustworthy, with ill intent toward white people. Because of this, such selective whitewashing perpetuates negative perceptions of people of color, while erasing positive representation of them from their own narratives.

For the love of Hallyu

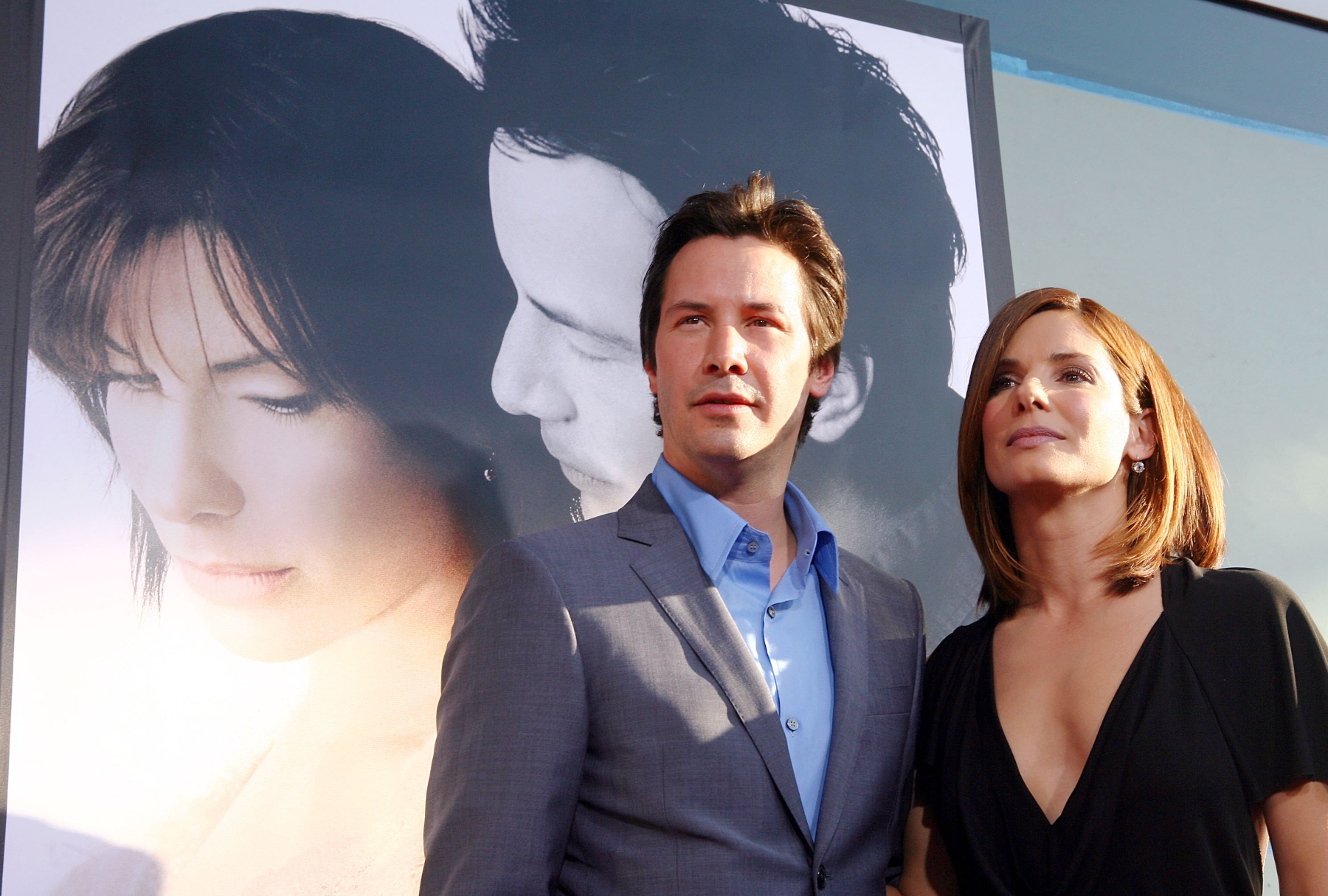

Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock arrive at the premiere of Warner Bros. Pictures’ “The Lake House” at the Cinerama Dome on June 13, 2006 in Los Angeles (Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

Keanu Reeves and Sandra Bullock arrive at the premiere of Warner Bros. Pictures’ “The Lake House” at the Cinerama Dome on June 13, 2006 in Los Angeles (Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

South Korean content is also targeted. As far back as 2000, Lee Heun-sung’s film “Il Mare,” about two star-crossed lovers communicating across time, was remade into “The Lake House” starring Sandra Bullock and Keanu Reeves (who, while of partial Asian descent, mostly plays white characters). In 2013, Spike Lee’s remake of Park Chan-wook’s famous action-thriller “Oldboy” received a very lukewarm reception.

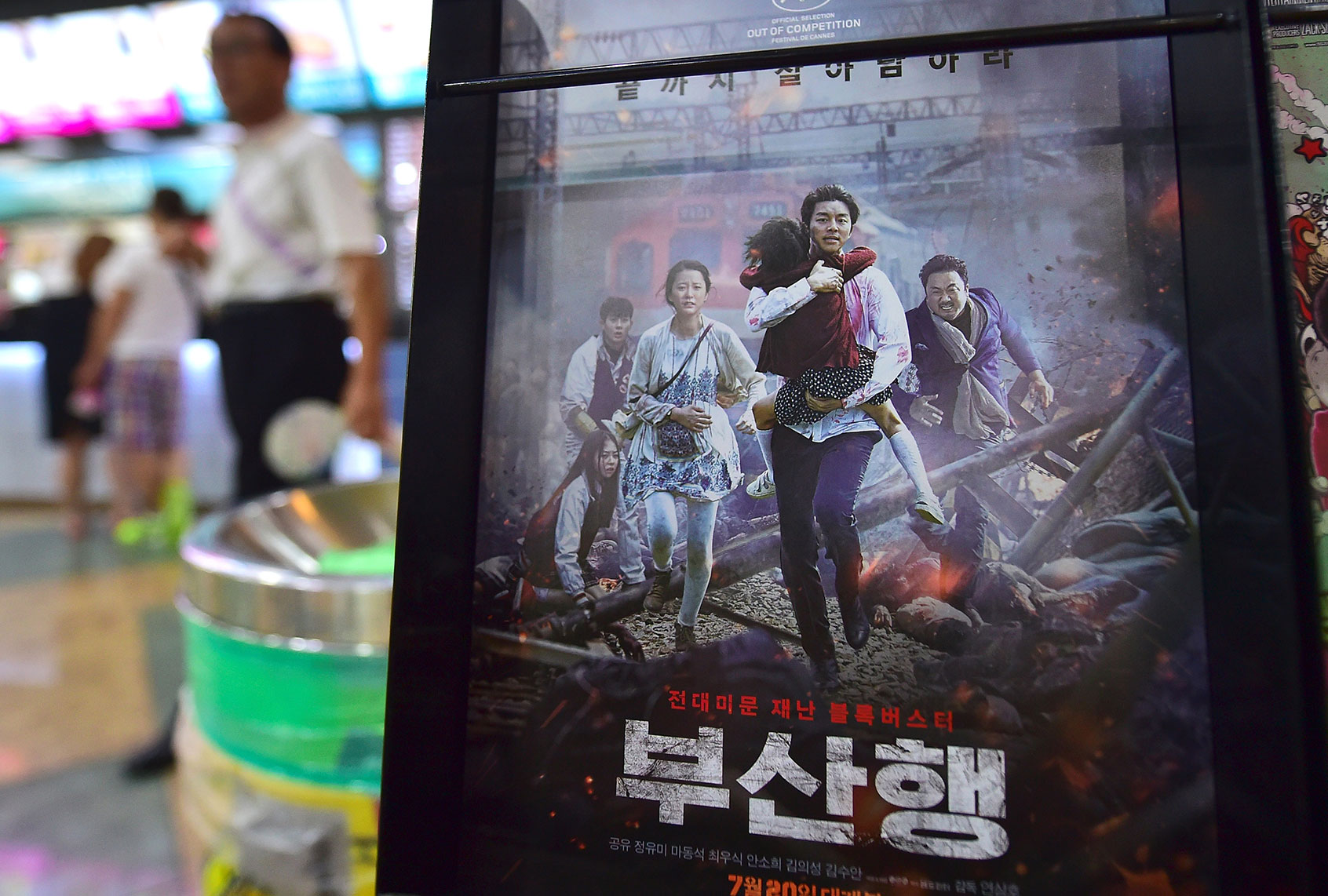

But now there are plans to remake Bong Joon-ho’s class-war thriller “Parasite,” which won the best picture Oscar last year, and Yeon Sang-ho’s acclaimed zombie apocalypse film “Train to Busan.” While “The Last Train to New York” has yet to begin production, the mere announcement has already created an uproar on social media with fans (me included) crying out their displeasure at just the thought of a remake being done.

RELATED: “Parasite” is a prickly, disturbing class-war thriller

Meanwhile, over on TV, networks have set their sights on adapting Korean dramas like the mega-popular “Crash Landing on You,” “Trap” and “Hotel del Luna.” Will they be as culturally respectful as Rodriguez was to his source material?

I have zero faith that this won’t be the case. Harsh, but true.

As a Black woman, cultural appropriation is behavior I’m all too familiar with, so when I noticed companies like Netflix and the CW announcing their intent to “adapt” Asian content, I saw a very troubling pattern emerging.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Why after all of these years are studios now paying attention to K-dramas? Why are they adapting already well-established and popular content, instead of developing original scripts by American creatives of color, by Asian American creatives in fact? There are Korean-American writers like Kayla Lewis and Luke Salin – who wrote and directed “Parked in America,” a dramatic series that debuted its pilot at this year’s SXSW Film Festival – who are waiting for the chance to share their stories with the world. But instead of giving them the much-needed opportunity for representation, networks like the CW want to remake the rom-com thriller, “W: Two Worlds,” in which the real world clashes with an alternate reality inside of a webtoon.

And then in a baffling move, Netflix – the same company that began streaming “Crash Landing on Your” two years ago to great success – is planning an American remake. Frankly I find this news to be not only absurd, but proof of a problem that is indicative of Hollywood’s obsession with trying to remake art by people of color, into their own white image.

This also highlights another fact – that Korean dramas are already accessible on multiple platforms for millions of viewers internationally, including in North America. Since the Korean wave of pop culture known as Hallyu in the mid-2000s, sites like Viki, WeTv, and Kocowa and the dear-departed DramaFever, have been providing streaming access for Asian screen content, not to mention Netflix getting in the game more recently. Furthermore, North Americans with international cable packages and smart devices like the Roku can find South Korean channels for dramas, news, sports and food. It’s all there, ready for viewing.

Why one cannot simply adapt Korean dramas

Son Ye-jin as Yoon Se-ri and Hyun Bin as Captain Ri Jeong-hyeok in “Crash Landing on You” (Lim Hyo-seon/Netflix

Son Ye-jin as Yoon Se-ri and Hyun Bin as Captain Ri Jeong-hyeok in “Crash Landing on You” (Lim Hyo-seon/Netflix

To say that what makes Korean – and other Asian – dramas unique in comparison to American shows is that they’re about Koreans and the Korean experience, would be obvious. And for some consumers that may seem like the best reason for American remakes and adaptations, to capitalize on that.

But on the contrary, that’s precisely the reason to avoid doing so.

Take the aforementioned “Crash Landing on You.” While K-dramas give romantic storylines that fans of the genre love, they also provide important historical and cultural references and context that international audiences are able to learn from. In this series, Yoon Se-ri (Son Ye-jin) is a spoiled heiress of a Chaebol family, who while paragliding is swept across the DMZ by a freak tornado (a fun tribute to “The Wizard of Oz”) into the North where she meets Ri Jeong-hyeok (Hyun Bin), an officer in the North Korean military.

As the two gradually fall in love, Se-ri and the audience are given a crash course on what life is like in the North, which has developed into a vastly different country since the Korean War armistice in 1953. Se-ri realizes just how privileged her life has been living south of the 38th parallel. For example, as someone accustomed to eating meat three times a day, she’s shocked to learn her new friends in the North keep meat as a delicacy to be enjoyed only on special occasions. She also grows to understand and appreciate the danger her presence poses because Ri Jeong-seok and his soldiers could lose their jobs and be imprisoned for harboring a South Korean national and suspected spy.

An American remake of “Crash Landing on You” would erase the context of Korea being a nation split into two because of a war that literally tore families apart, forever changing the genetic and cultural footprint of the country, preventing it and the people from progressing together as a whole.

Similarly, in trying to adapt “Train to Busan,” the idea of a bullet train as the setting for a horrific event is one that realistically doesn’t apply to North America because the film isn’t just about zombies set on a train. Instead, writer and director Yeon Sang-ho plays with South Korean tropes and subverts them to show that who we perceive people to be has no bearing on who they are morally. This can be seen with the character of father-to-be Yoon Sang-hwa played by Ma Dong-seok (Don Lee in “The Eternals”), best known for playing a tough guy.

Squid Game (YOUNGKYU PARK/Netflix

Squid Game (YOUNGKYU PARK/Netflix

And, despite the cultural specificity of these stories, many people living in North America are still be able to relate. In the case of “Crash Landing on You,” immigrants and refugees know what it’s like to suddenly find yourself in a strange land where everyone around you does things differently. Also, many refugees and undocumented fleeing dangerous situations live in fear that one day they could be arrested and sent back to the countries they fled. In regards to “Train to Busan,” many have felt trapped in the lives and identities we’ve built ourselves, and must find the courage to break free.

Therefore, the argument to adapt these properties to make them more relatable for American audiences doesn’t hold up. We like them already in their original form. So when you really dig, the only reason to remake them is for profit.

RELATED: “Squid Game” and the real debt crisis shaking South Korea that inspired the hit TV show

And in doing so, this removes the important facets that make these shows and every other K-drama special, loved and meaningful not only for viewers within and outside of America.

It’s cultural appropriation of their media.

As with all cultural appropriation, the practice is racist and xenophobic because what these remakes tell us is that for content to be “palatable” to Americans, the stories must be from an American perspective and portrayed by Americans who speak English. It’s telling me that Americans have the perception that listening to people speak in another language and reading subtitles are still considered too much of a hassle for American audiences.This is not only insulting to Koreans and anyone who speaks a language that isn’t English, it does a huge disservice to the audience as well, because it demonstrates that studio executives believe American audiences either don’t have the capacity or willingness to grow and learn, and appreciate anyone who isn’t them.

It’s also patently false. All of those reasons have been disproven yet again with the breakout hit “Squid Game” this year. The thrilling series about desperate and impoverished people competing in death games for the chance at millions is fully rooted in the state of South Korean today, while also critiquing the fallout from splitting the country. As Netflix’s No. 1 show worldwide, it proves that such a specific story can still be relatable to multiple cultures all over the world.

And this success was achieved through a foreign-language TV show.

The push for an adapted “Crash Landing on You” is particularly ironic for Netflix because of the mega popularity of “Squid Game” and Spain’s series “Money Heist,” two successful non-English shows the company boasts about. Viewers of “Squid Game” didn’t just embrace the show with its subtitles and all, but many have even been inspired to take up Korean language lessons to better understand that and other series along with all the other joys – such as K-pop – that Hallyu brings.

By pushing for remakes, what these studios are doing is proving that despite the claims of increased diversity and inclusion, Hollywood is still very much interested in maintaining the status quo that white is right.

Read more about Korean dramas: