The idea of being Black and poor in America often makes people think about the gun violence, drug trade and pain that wraps the existence of that reality. And because those factors are prevalent means that too often we overlook the joys that make up the heart of the community. These joys exist by way of family gatherings, community affairs like block parties, and other forms of fellowshipping, with one thing tying all of these types of events together –– dancing. You better know how to dance.

My dad, one of the best dancers I know, once faked me out –– by telling me that we were going to the Exotic Auto Show, which comes to Baltimore every year around my birthday. So, we jumped in his car, picked my cousin up and headed down to the arena. Dad forgot his wallet, so we had to go back to the house and when I walked inside, “Surprise!” was yelled by my whole family and the bulk of my block. Before I could catch my breath, my cousins surrounded me telling me that I had to dance, my crush La Tesha was there, and it was a requirement. The only other option was me leaving my own party, kind of putting me in a dance or die situation. I was a little kid and didn’t really have any moves (and would never really learn) but I quickly picked up the Black-Dude-Two-Step, which is a left to right, front-back movement that allows one to appear to be on beat for any song at any function. My friends still know I can’t dance, but it doesn’t stop me or them from joining in and celebrating the love of something that is special to us. Author Hanif Abdurraqib captures the beauty of the history of dance and its relation to Black America in his new book, “A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance.”

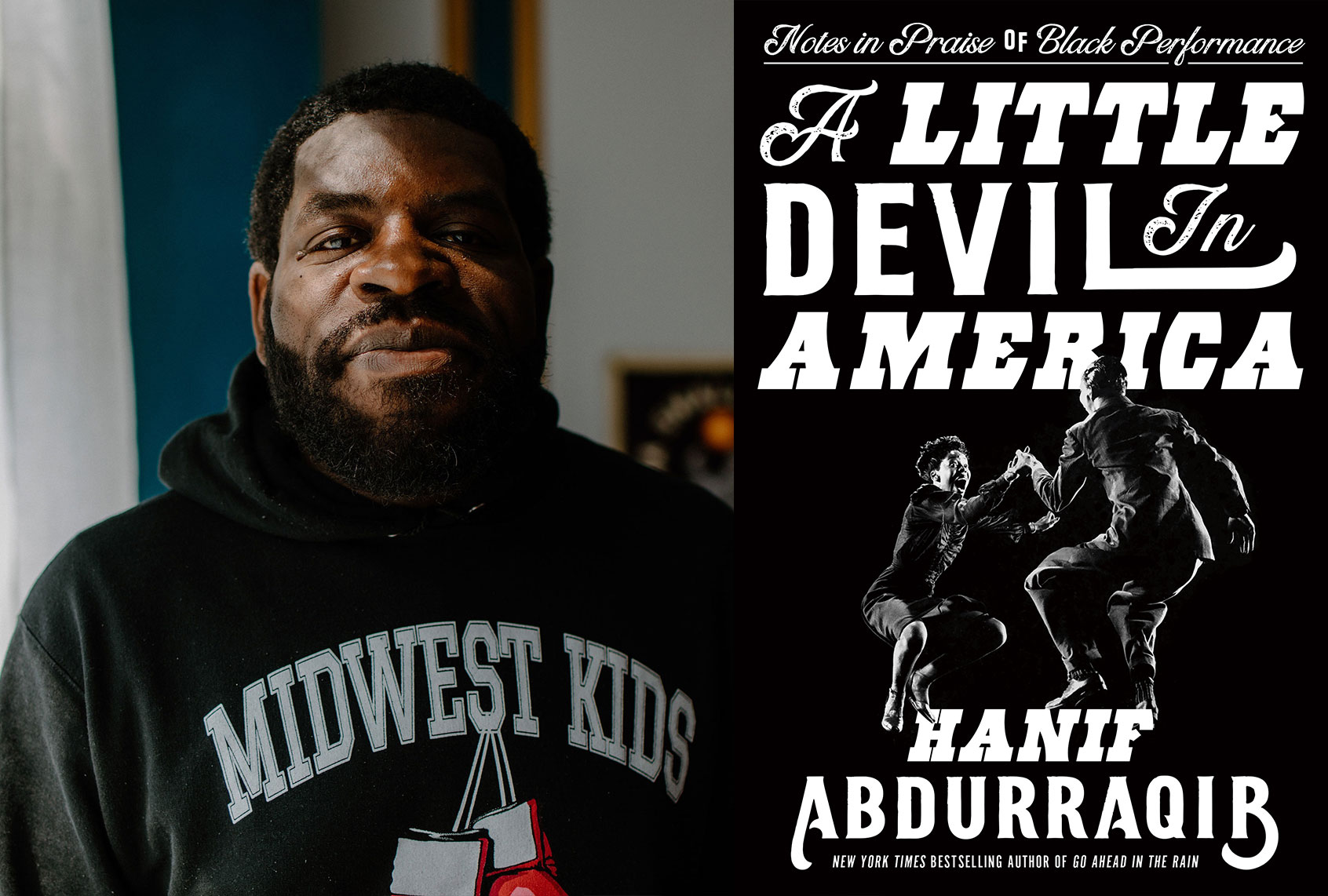

Abdurraqib, the award-winning and New York Times bestselling author of “Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest” and “They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us” is back with a brilliant collection of personal essays that circle around Black people performing in the America, both publicly and privately. Abdurraqib joined me on “Salon Talks” recently and explained how “A Little Devil In America” covers everything from the true history of Don Shirley that was left out of the Oscar-winning film “Green Book” to how Don Cornelius built his “Soul Train” empire.

Watch my “Salon Talks” episode with Abdurraqib here, or read a Q&A of our conversation below, to hear more about the history of Black arts, what COVID did to his sneaker collection and the enthusiastic dance moves that got him through high school in Columbus.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

I love how you love Ohio, man, Columbus. I love how you love where you’re from. I feel like being from cities like Columbus or a place like Baltimore, I feel like we’re always the underdog when we’re fighting with different powers in New York, or Atlanta, or L.A., right? We come in and we do our thing and then we proudly go back home.

That’s it, right? My parents are from New York, and so much of the pop culture that I consumed in the ’90s, especially Black stories, were about like coastal stories, like “Juice,” “Menace II Society,” “Boyz n the Hood,” all that. I realized at a pretty young age that there were Black people everywhere kind of living stories that were not dissimilar to those stories that I was consuming. I got really fascinated with regional Black culture. Baltimore is a really good example of this, where it’s like – nowhere else is like Baltimore and no one else are like the Black folks in Baltimore. And it’s like that in Detroit too. I feel like Detroit is its own central thing. Loving where I’m from in a way, it’s kind of just embracing my complete understanding of the way my people move in the city I love and understanding that it’s not like anywhere else.

How have you been holding up with this COVID stuff and how are you handling the rollout of your new book when everything is virtual?

I’m going to honest, in 2019 and early 2020 I was on the road all the time, I did like 120 readings or something in that time. So if I’m being real, being home has been good. I wish it was under different circumstances and I wish it did not come with all of the tragedy that it’s come with, both in my own life, but also globally, but I do think that I almost needed to slow down. I needed to hit a point where I could settle myself in Columbus and reassess my own priorities.

Now, putting the book out into the world, I miss the kind of physical nature of being in front of people and reading the work and hearing the way a room is reacting to the work in real time. But there’s something about the accessibility of the virtual space that I’ve really enjoyed too, where I can connect with folks from all over, people who’ve come through from all over, and I do hope that’s a trend that kind of remains post-whatever, post-a-pandemic world looks like if there is to be one. For me personally, I fell into healthier routines and I’ve been a little bit more generous with myself because it’s just me and I’m just at home by myself. Spending that time alone is good.

Healthier routines like what? Like you changed your diet, or . . .

Well, a little bit. I spend some time meditating now. I have a more scheduled, thoughtful writing routine. My workout routine is a bit better. I’m sleeping better than I’ve ever slept. I’m getting like a solid eight hours of sleep, and it’s just because I’m not always on the move. I’m not in like three different time zones a week. And all of these things lead me to be a better person, a better more careful, more thoughtful person, which leads me to be a better writer. It’s all kind of interconnected for me.

That’s fire. Sometimes I fear becoming a better person, because I think it’ll mess my art up.

Nah. One, you’re already a good person. You don’t got to worry too much, but if anytime you become a better person, the art will follow. It really will.

Word. I’ve been following your work for a minute and I’ve always appreciated how much you love doing readings. It’s a part that a lot of writers struggle with, even successful ones. They want to be able to protect the way they sound on the page. How are you going to try to keep that part of it together?

Everything’s virtual. I have no in-person event planned until like November, and even that’s tentative because it’s so unpredictable. But I still try to kind of bring my all to the virtual reading space. So much of what I love about the in-person reading is just the sounds of the room and the sounds of the people in the room. It took a minute for me to adjust to the fact that I’m just like in my own house immersed in nothing but the sound of my own voice, and then silence. It’s kind of like if you take the crowd out of the arena and you just hear like the feet squeaking on the basketball court. That’s kind of jarring, but I still try to bring my all to the reading space. I write the work to be read out loud, I’m always thinking about the musicality of language and the pleasure of sound. So much of the work is written to be performed.

Speaking of performance here we have your amazing new book, “A Little Devil in America.”

Thank you.

Can you first explain the title and just break down the cover for our readers?

The title is a quote from Josephine Baker‘s speech at the March on Washington, which is a speech that I love and a speech that often gets written out of the history of the March on Washington. People kind of cherry-pick Black history. Josephine Baker, at the March on Washington, gets written out, but I love that speech and that particular line comes from a point where she was looking out on the younger audience — because she was a much older performer and a much older person coming back to the states for the first time in a long time — and she looked out on that audience of younger people and she said this line about like, “Go and ask your parents about me. They’ll tell you I was a devil. I was a devil in other countries and I was a little devil in America too.” I love the way that Black folks remind people of their greatness and are unafraid to, but have to do it repeatedly, as Little Richard did for example as well. It felt fitting for the book.

I’m so hands-on with my covers. I take it real seriously, and we went through a lot of different iterations of the cover. We got really close sometimes, and I’d be like, “That’s the one,” and then I would sleep on it and wake up the next day and be like, “No, no, no, that’s not the one. We got to do a different one.” And we landed on this one. I landed on this because I really liked these photos of Lindy Hop aerials, and I knew I wanted a photo that showed Black people in the midst of something spectacular.

There’s Willa Mae Ricker and Leon James’s photo from 1943 doing a Lindy Hop aerial. I just love her face. I love that she’s kind of like she can’t even believe what she’s doing. When I was writing the book so many times I was like, “I can’t believe this book came so easily to me.” I was like, “I can’t believe this is happening.” I wanted to capture that awe in the photo.

You start the book off with talking about dance marathons. It was a wild and crazy time to be alive. What was that world was like?

I didn’t know these things existed, these Great Depression dance marathons, until about three years ago when I was working on the book, and a homie hit me to them. It was horrific. People who did not have much, did not have shelter or food were performing in this way where they were just dancing for, not just hours, not just days, but months, months and months and months and months. Some of them just to get shelter and three meals a day. In some cases the second place didn’t win anything. If you danced for 1,457 hours, which some people did, you won, but if you danced for 1,456 hours and 55 seconds you got nothing.

That’s crazy.

And that’s just pretty horrific. I knew that it was an entry point into this idea of dance and endurance that I could use as a gateway to get into “Soul Train,” and the somewhat marathon run that “Soul Train” had. Also, the “Soul Train” mind, which is less about endurance and more about precision and kind showing out in this small window of time. Of course the dance marathons were largely white folks. I was just fascinated by those parallels, those somewhat horrific parallels.

You’re a sneaker guy. If you had to dance for 1,400 hours, what kind of shoes you wearing?

I’m thinking about those sacai Waffles, just because they’re so comfortable. But I also just got those like Undercover joints with the Chaos and Balance on them, and those might be the ones too, because the cushion in the back is real. What are you wearing right now? What are you wearing out the house?

I’m wearing the newest sacais. I grabbed every colorway of them, but I’m not dancing 1,400 hours in those. Jordans still, bro, and just a lot of slip-ons.

A lot of slip-ons.

I feel like I’m Cali right now.

Yeah. I can’t wait to get back out. I’ve gotten so many sneakers during the pandemic.

They’re killing me. Oh my God. These sneakers, they’ve been killing me. I already know. I already know, and they’re all in boxes.

All in boxes.

1,400 hours though, I think I might be going with some 992s or 991s, bro.

I forgot about New Balance. I only got one pair of 991s. I might have to put them on for that.

Another thing about this book I liked a lot is the way that you dropped in with bits and pieces of your personal story. One was about when you guys danced in high school and that was a way for the Black population of the school to connect. Could you dance?

I can’t dance that well, but I’m an enthusiastic dancer. I know how to get from point A to point Z on the dance floor without f**king up anyone else’s good time, which I think that’s vital, because you have people who can really, really dance and you’ve got people who really can’t dance. I like being in that middle ground where it’s like I know how to stay out of the way and have my time in my little corner and let the people who can really dance take up a lot of space.

I don’t need the spotlight, just a two-step. How did the rest of the school, like the non-Black population, respond to that?

It’s wild, because when I look back at that time, ever since I wrote that piece in the book and people have read it, everyone wants to talk about it. When I look back at that time, I just thought this was happening at every high school all over the country. But it’s so wild. High school, you’re eating lunch at like 11:00 AM. We’re having these like sock hops in a dark gym at like 11:15 in the morning, everyone’s sweating, all these teenagers grinding up on each other and whatnot. Then we just got to go back to class. By noon, we’re back in chemistry class just still sweaty or whatever.

It’s an incredible phenomenon. It felt really innovative in a way because it was like the school’s way of saying, “This is how we know we’ll keep these people here, because if we let them leave during lunch they ain’t coming back. We got to make something enticing enough to make them want to stay.”

Much like in either city, to be Black in Columbus is regional. I’m from the east side and to be Black on the east side is different than what it is to be Black on the north side. In my high school there were Black kids from all over the city, and to have this point where we could all kind of come together and rock for a bit and then go back to our classrooms and be the people we are in our classrooms, it was kind of beautiful, because it let me in early on the fact that Black people can be multiple things at any time during any day.

It’s crazy that in 2021 we still have to push that nerve that we’re not a monolith. Some of us listen to this type of music, some of us are into that type of music, and then some of us love it all, and it’s totally okay, like any other group of people.

You mentioned “Soul Train” earlier, and you write about Don Cornelius in the book. I think that was important for the culture just in general, because people don’t know Don Cornelius was a mastermind, a business mind. He owned the whole franchise, right?

Yeah.

What should people know about Don Cornelius?

Coming up, he was a big deal in my house, mostly because those reruns would play. If you came up without cable, in Ohio, and Columbus specifically, you would still get WGN, the Chicago network, and they would just play old “Soul Train” reruns on Sundays all morning long. I just grew up as a kid immersed in Don Cornelius’s cool. He was a cool mother**ker. The outfits, his voice, the way he talked, and the way that musicians revered him. Musicians really cared about showing up on “Soul Train,” just showing out.

In my household he was someone who was really revered, and it was good for me as I got older to find out more about him, his business mindset and his full vision for the fullness of Black people. The era he came up in and what he saw in terms of the Civil Rights Movement and the way that he knew that music could be propulsive as a method to get people to freedom. He was visionary in that way.

Two of my favorite chapters in the book were one about you playing Spades, and then the other on Don Shirley, another person who people don’t know enough about, until they saw the movie “Green Book,” which you weren’t a big fan of.

Nah, man.

I ride with you on that one all day. I wasn’t the biggest fan of “Green Book,” I’ll just say that. Happy for the people involved and its success, but I wasn’t a big fan of it. Talk about you as a Spades player. What is that Spades culture? Was it something you guys did for money, or was it something that you picked up as you found your way into your artist community?

Well one, I’ll say as Spades player I’m much like a dancer, where it’s like I probably need a partner who’s better than I am, and then I’m steady, but I’m a get out the way. I don’t want to give away too much of my spades.

Give away? Nah, you can’t get out the way of your Spades. It don’t work like that.

I definitely don’t play it safe every hand, but one thing I’m really good at is looking at my hand and being able to pinpoint exactly how many tricks I could take. There comes a time to take risks. If a partner goes nil, I’m an elite. I can hold you if you go nil, almost no matter what. But it’s because in my house we played Spades. I’m the youngest of four, so having older siblings and having parents who played cards and coming up in a neighborhood where people play cards and coming up around hustlers who play cards.

I don’t even remember where I learned Spades, but I feel like I just learned it by watching. No one ever told me like, “This is how you play.” I was just around cards. We played in high school for money. Definitely played in college for money because at the college I went to there weren’t a ton of Black folks, and we all hung out together, and all we knew was how to play cards for money. College is where I really learned that depending on where you’re from, people just play Spades differently.

Did you guys come up playing Tonk?

I played Tonk a little bit, yeah, but it wasn’t in my house. We didn’t play in Columbus. I didn’t learn it until college.

It’s such a regional thing that everywhere you go the rules are a little different.

I had no idea what it was until like one of my homies in college, he was from Alabama, taught me. I’m sure people play it in Ohio, but in my neighborhood no one was playing it. Spades is so fascinating to me because the story of Spades, in a way, is the story of Black migration where depending on where you land on the map, someone’s going to play it a different way with a different language, a different set of rules.

And on Don Shirley. The “Green Book” movie didn’t really do enough to show what the industry did to Don Shirley.

Yeah, and the thing about it is, I really wish that Hollywood would maybe divest from this idea of Black biopic movies because I think that so often the work is to condense Black life, a full Black life, into something that will make non-Black people feel good, or feel good about this vague idea of American unity, which that wasn’t Don Shirley’s job, and that wasn’t Don Shirley’s full life.

I can’t speak for Don Shirley, but that wasn’t, for me, the most interesting thing about what Don Shirley contributed to American culture. None of that was. Mahershala’s performance was a beautiful performance, on the whole but that movie was not for me. As someone who grew up listening to Don Shirley and was very interested in Don Shirley, I probably went into that movie with the wrong expectations and came out of it very frustrated. But it also was a pattern of times I’ve gone into movies that are supposed to be made with a full Black life in mind and walked out understanding that the movie was made to placate a non-Black audience.

Hollywood is starting to be fascinated with also telling the stories of these courageous Black people through the lens of informants and snitches and the people that tried to bring them down, and I’m hoping this is a trend that will end quickly. Hopefully we get past that.

We got to.

When I read your writing and I always think, “Wow. This guy can write about anything,” but it seems like that you are pulled towards music a lot, right? Your Tribe Called Quest book “Go Ahead in the Rain” being one of the great examples of that. What draws you to music as a fan or as a person who connects with it enough to dedicate a whole project to it? Are there any current artists that you feel like you could write a book on?

Oh course. Well, current for me is like folks who are still living who I think deserve their flowers, like Miss Patti LaBelle, or I was thinking about Gladys Knight the other night, or Sly Stone. These folks. But music has helped me make sense of the world. The way that music has created a map for me and unraveling my own emotional messes has allowed me a clarity that I can approach the world better with, and I think I owe an articulation of that in my work. I owe my work to that.

I owe how my life has been soundtracked. In the book I write about ’02. I write about The Diplomats and Juelz Santana. I remember that era more than I remember most anything else. When a soundtrack is the most immense part of my lived experience, I think I owe it to that soundtrack to be real about that. I will say though, my next book is about basketball. I’m writing a book about Ohio, the high school era of basketball in Ohio from like ’94 to 2001, the LeBron James era, because I’ve always wanted to write a basketball book, and I know I’m kind of preaching to the choir. I know Baltimore’s high school basketball history is well-documented, and as well-documented as it is, it’s still not enough, because you all got a history that’s maybe better than any other city.

Bro, I’m writing Carmelo Anthony‘s memoir, so I’ve been in the basketball world the whole past week and I’m kind of like, “Oh, I want to go deeper.”

I’m fascinated by the era of high school basketball and who makes it and who doesn’t, and what making it is defined by. Then I got to thinking about Columbus and how we had some runs that were not like that, not as great as that, but like similar when I was coming up. Great ball players that came out of here, Michael Redd, Kenny Gregory, Estaban Weaver, that led to this LeBron James era. I wanted to write about that. So yes, of course I write about music primarily, but in the back of my head always there’s a basketball book I want to get to, and I’m really excited to get to it next.

Your work does so much for living Black artists and I think it’s extremely important. I don’t know if that’s the goal for you, but how do you see the larger context of your work?

I think so much of what I’m trying to do is give people their flowers in real time, or to re-contextualize someone’s living so that it is fully appreciated before it gets swept away by history, or before it gets reformatted for an audience that doesn’t have the best intentions for that person’s full living.

When I think about someone like Merry Clayton, who I write about in the book, I wanted to give her her flowers through the only lens I could, which is deep gratitude before someone kind of wrestled that story away and then reformatted it to serve a different audience. It’s kind of like plugging the leaks that history punctures. So often history punctures a legacy of these Black artists to make them more palatable, and I’m trying to plug those leaks to say, “No, no, this is a full person who does not need to be drained of their radical history, or their revolutionary history, or just the fullness of their life that did not serve the machinery of whiteness.”

Facts. You create so much literature. You write a lot. You have a lot of stuff out. What are you doing right now as far as what kind of art are you consuming outside of just your own stuff? I know I get tired of myself.

I’m sick of myself right now because I’m in the book cycle. I’ve definitely been running into other art. I’ve been reading a lot of poems, a book, “Inheritance” by the poet Taylor Johnson, which I love a great deal. I keep it by my nightstand. The book “All Heathens” by Marianne Chan, which I’ve been rocking with for months. I’ve been reading a lot of Black punk zines, old and new, that I get from this spot called Brown Recluse Zine Distro. I’ve been really on old Black magazines that I get from like BLK MKT Vintage, like old Ebony. Just kind of immersing myself in the way profiles used to written, all this kind of shit. And music, man, every Friday I’m listening to new stuff. The album that I’m super on right now, Starrah’s new album. Joyce Wrice’s album.

And then sneakers, I’ve been on this tip lately where I’ve been trying to go back and get like OG joints, like original joints from the years. Early in the pandemic I got the original 2000 Space Jams, and I got these ’94 Bred Jordan Ones that I had to send out to get resoled because the sole was kind of starting to crumble a little bit so I got those refinished.

I gave my nephew some original Space Jams, and this fool went out and hooped in them and they crumbled.

Yeah, you can’t hoop in those joints. You got to take care of them.

The problem with the older sneakers for me is that technology has changed. Some Jordans from the ’80s is not going to feel like the Retros. The Retros got like new cushion, new technology. They feel a little better. You ever think about that?

Oh yeah. Some of them ’85s feel like you’re walking straight on the concrete. And that’s why I will wear them, but I’m a wear them like very selectively, like maybe once or twice a year. Not because I’m on some s**t like I got to protect them, but because some of them joints, if you wear them long enough in a day it feels like you’re straight walking on the actual concrete with no shoes on because the cushion’s not there. They were made kind of specifically for hooping in, where some of the Retros were made for fashion in a way. So I feel like around ’96 is when they kind of started being better for just like everyday wear.

In Baltimore all we wore was like the Foamposites and Uptempos. I remember when the Pennys first came out and going to New York and playing this basketball thing. New York dudes were so in awe that somebody would not only spend $200 for a pair of sneakers. That was kind of rad back in 1996 for you to pay $200 for some sneakers, but let alone pay $200 and hoop in them. Foamposites becomes this big thing in my region, and then D.C. It goes back and forth with Baltimore over who came out with Foamposites, who came with the New Balance, who came with this and that.

I think for me, I have a couple pairs of Fives, but I’m really big on like Ones, Threes and Fours and 11s. It’s funny, when I was a kid I would cop anything, but now it’s like I look at Sixes and Sevens especially and Eights, Six, Sevens, Eights, I’m like, “Yo, I maybe gassed those up when I was younger, but these shits ain’t hitting.” Eights are so weird, because you can’t even like tie in them, and like strapping them up . . . It’s like, “Yo, I can’t. These don’t do it for me.”

We could talk about sneakers all day. Can you drop a couple of words for some young artists trying to find their voice or just trying to figure out how to master being themselves? So many people feel like they got to sound like this person, or sound like that person.

I think I was lucky in that I came up reading widely and taking inspiration from a wide number of places, and through that I think that you build your voice, or I built my voice, out of the pieces of many other voices. That how I think you become an authentic self, is that you don’t tie yourself to one writer or one artist and chase only that inspiration. You perhaps allow yourself to flow.

I’m as much Morrison as I am Virginia Hamilton, as I am Zora Neale Hurston, as I am Adrian Matejka, as I am Terrance Hayes, as I am Khadijah Queen, as I am Tyehimba Jess. All of these folks I’m borrowing from to build up a voice that feels authentically mine. Pursuing the excitements that I find in their work has informed my own, and then you’re really yourself, because you’re taking percentages of other people that make up your own and you’re not taking the same percentages other people are going to take. Build your voice out of the many parts of others and you’ll never be like anyone else.

Tell everybody when the books drop and where they can get it.

“A Little Devil in America” comes out March 30th. You can get it anywhere. Try to cop it from an independent book store if you can. Support those. If you’re in a space that has a Black-owned bookstore, definitely slide through there. And the Black-owned bookstores have been so great to me through my career in general. Like Loyalty in D.C. and Source bookstores in Detroit and Marcus in Oakland, and a lot of these are institutions that deserve our support.